"THERFORE THY BOKE OF COUNTE

advertisement

"THERFORE THY BOKE OF COUNTE I,J ITH THE THOU BRYNGE":

A RE-EXAt11NAT10N OF THE t10RALIT1ES

An Honors Thesis (1D 499)

by

Lisa A. t10r r i s

for·

Ball State University

t1uncie, Indiana

Apr i 1 1989

for graduation from the Honors College May 1989

CONTENTS

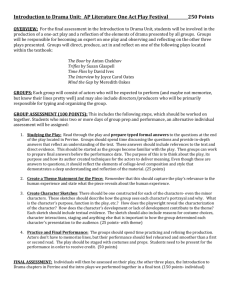

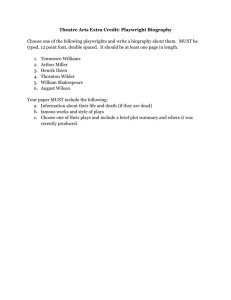

INTRODUCTION

HISTORY

4

CHARACTERI ZATI ON

8

t1anK i nd

I..) ice

Virtue

Death

God

STAGING

Costuming

Proper- ties

t1us i c

Gestures

Scenic Practices

9

12

13

16

18

19

20

20

21

22

22

INTENT

24

CONCLUSION

27

APPENDIX I

2S'

APPENDIX I I

32

BIBLIOGRAPHY

33

the

"When compared wi th

achievements

of

Renaissance

drama in which the supposed evolutionary process was said to

have

to

every form of medieval drama has been found

culmjnated~

be

different

and not only markedly different from

to

infer'ior

(T.::"ylor'

them"

3).

c r' i tic ':;, the' r' eli g i ou s dr' ama

technique

dra,ma tic

or

,;:tf

the

as

drama

the

dramatic

only

Middle

purpose,

of which it

toe x c e l i n in':;:, tan c e s

yet

it

0

far

"had

ha-=:,

Conver':,e 1 y,

dramatic form

is a part.

f c om i c but not

0

f

no

and no a,r't i st i c

been

because of its roots in ritual

been denied acceptance as a full

r' i t u a 1

but

Ages

dr-am.:.,

commonly accepted birthplace of theater.

r' eli g i ou -=:'

progeny

According to many modern

self-consciousness" (Taylor 4).

viewed

i ~::e them,

from its offspring rather than

due

the

it ha':,

to

the

"It has been said

tragic

ar't,

and

has been taken as serious in intent and without any

aim to amuse"

(Taylor 5).

art

And

i r' on i c

,;:0.

1 1 Y,

it-=:,

as art,

it has been denied examin,::"tion" a,s such (TaT"lor' 5).

y

not

most

"since

\..~I.:O'-:'

all egedl

perhaps

intended to be thought of

It is this narrow interpretation of drama that I refute

in this paper'.

colorflJI

a,nd

"The

~.Iar'

centuries to which

and

the

devil

i ed,

thea ter'

as

of

full

it belongs.

the

Middle

Ages

is

=--=

--"-'

of 1 ife and contrast as the

It holds discourse with

God

bui lds its paradise upon four plain posts,

and moves the whole

universe

wi th

a

It amazes me that cri tics can consistently dismiss

228) •

the plays and their characters as "bloodless

as

~.e

<Ber·thol d

windlass"

abstractions~"

if they were nothing more than a series of dreary Sunday

Perhaps in the plays the Virtues

r'mon -=:..

and

moral

Vices who

dr inK i n g,

but

izing~

often

.:~n

stagger

onto

they

often

meeK

could one so readi ly dismiss the

are

l.:..ughing,

stage

d f ':'.r· tin g, 'A,h i 1 e all

Surely

1'"1an 1<: i n d'?

how

are

-=:.hout i ng,

the time sc h em in g to ambu sh

portrayed

as red-blooded and

robust, hardly "bloodless abstractions."

Per'haps

partially

the

at

t e r·m

fault.

and convictions that

instinctively

"r"lcor' .:0. 1 it)'"

in

that

mayor

resent

this

of

j -;:.

r"lorality implies a set of conventions

the

may

beha~.1

not

i ora I

moral

"classroom"

theater, a place where we feel

we

be

our

own.

We

instruction the word

" m0 r' a 1 j t y " imp 1 i e ,:., and t h .:.. t r' e -=:. e n t men t

f.:o.c t

and

i ,:. am p 1 i fie d by

the

is contained within the

should

be

entertained.

The outlook for these plays becomes even worse when the word

" .:0.

i ,:. t h r' o . . . 'n i n tot h e rna t t e r .

lIe gcor' i Cd. 1 "

suggested that to avoid such

call ed

stigma

in ter·l ude,:.,"

"mor' a 1

cor'

audiences, just "interludes."

t e r'm i no 1 og;v' ,

for'

the

per·hap,:.,

Some cri tics have

plays

should

be

in or'der' to dr'aw

But I question the change

in

the de 1 i n eat i on be tt.·.'e e nth e t e r·m-=:. i -=:. h az ::r"

at bes t .

Despite the pejorative nature of the term,

its advantages.

it does have

The term "Moral ity" forces us to accept the

2

claim

thE?

UI,:d

play,:,

instructioral motive or

moral ize.

They

do

are

not

outdated,

They are

dreary

much

sermonize.

farces

these

Indeed,

than

Despite this,

these

"simpl e

fossi I i zed

of

without plot, wi thout character,

a I mc.s t

(,." i thou t

~)

a 1u e

pap e r •

intent.

of the

hope

to

are

... ,

drama,

con f I i c t ,

i ':' the I i f e

trace

wi thin

To do t hi,:, lin ten d to emp I o:~' a, br- i E? f hi,:, t c.r' :~. ,

the n s e gm e r t s de ,3, lin 9

and

do

orations.

modern

i ':, hi,:, t or i c a I" (T ,:.,y lor' 7). I t

and the vigor of these plays that

t hi,:,

plays

te~d(s]

amoeba

on 1 )'

wi th no

plays

unbearably dry, humorless and dull

more

to

They do try to dirE?ct their

undifferentiated

wh c'':,e

I ittlE?

ight-hearted

value.

audiences toward salvation.

in ten t i on

It is not m::.'

plays for what they really are.

l~.1

i t h for' m, c h a r' act e r' i z ,3 t ion ,

staging,

From there I wi I I end wi th a brief discussion

impact of these plays upon later dramatic

Ii ter'a,ture

and the distinctive mark they left upon world theatE?r.

It seems theater and ritual have always traveled hand in

Theater

hand.

ear·ly r·el

the origins of theater to

tie

and r·itual i-=:.tic pr·actice-=:.

i~dou-=:.

v.Ji thin

pr·imi

From there Western theater rose until

soc i e tie·:. •

its.

historians

he i gh t

whi Ie ri tu.=d

in Rome

in the fourth century A.D.

br·ou(~Jht

theater

intc. the ',<Jor·ld,

was

the

Both

church.

that

time

the Church and

invading conquerors served to extinguish the theater.

last

defirite record of a performance in Rome

The

is found in a

let t e r· (>.Jr· itt e n i n

Al though

continued

it does not seem to have survived

on

after that,

the Lombard invasion in 568.

been

the

final

theater

invasion

may

seems

blow which pushed the theater bacK

"obscurity out of which

ea.r·1 i er· n <BrocKett 84).

persecu t i c.r,

That

the

~

it also r·emot.!ed

The theater's major source of opposition at

Christian

it reached

I r· on i c a I 1 y

it.

rising

ti~!e

helped

have

to

have

into the

it had slowly emerged some 900 years

Oddl ::-' enough,

break

down

the

af ter·

Church···s

organized theater,

it also

helped to rebuild it.

Theater· had it-=:. r·ebi r·th

parts

in

the

Chur·ch i -=:

were distributed among "actors"

the point of the Scripture.

It

~"I':'. -=:·n

.:..nd e'·.!en (.<Jhen it did,

4

it

' tun til

wa~·

~

in order to reinforce

the I ate

Ages (c. 1300-1500) that drama began to emerge

church,

1 i tur·gy

~'1

i dd I e

ou t side

the

still hi.;thlY religiou-:.

in nature.

The majority of these extant medieval

drama. t i za. t ions

of

B i bl i cal e'Jen ts.

plays

are

The dr.:'i.ma of th i s time

found its roots in the re-enactment of the Resurrection,

e'·)en t

to

cen tr'a I

the

development

of Christianity.

in

there writers of the time reached back

Creation

and

history

evolved.

At nearly

time, a smaller body of plays was evolving.

k n c'I.··m t 0 d a}' a =. " m0 r' a lit y p I a :;00' .::.•

to

moral i ty

play,

the

the

grew

the

and

same

These plays are

"

secular

form closest to the

cycle plays, first appeared in the late fourteenth

It

From

forward to Armageddon, and the mystery cycles

tracing al I of human history

The

an

century.

flourished along wi th the miracle and mystery

plays durirg the fifteenth century and shared much with them

in the

wa)'

of

staging,

characterization

and

structure.

un like

new genr'e, having no precedent in the e·:'i.r·lier· church

drama.

Perhaps because it was not as firmly rooted in the church it

was

more adaptable to "new ideologies and social condi tions

during the sixteenth century than ... other kinds of

drama,

and thus survived to become a formative

the Renaissance drama while the

found

themse 1 l)eS

cycles

i ncreas i ngl >'

and

under'

medieval

influence on

saints'

.:<.tt.ack

by

the

Reformation Church" (Bevington, Drama 791).

Like

"Chr' i =.t i .:..n,

the

cycle

plays,

the

an 0 n ym 0 u s., and " pop u I a r' ,"

be performed for the general

mor' a lit :;00'

1.~:YS

are

I,. . r' itt e n i n E rll;t Ii:. h t c,

population"

co

~,

p

(Potter 6).

tv lora I

personifications

such

as

Death

and the seven Deadly Sins

.abound not on 1::.- in the all egor' i ca 1 mc,r'a 1 i ty play-=:o bu tin the

N Town pageants and the

,Ju-:.t i ce,

Truth,

moral

j

saint's

r'1er'c)-',

and

play

Peace

of

Mary

a r' e

Magdalene.

in

f eat u r' e d

the

ty play The Castle of Perseverance, but also appear

the N Tow n p age .~. n ton the par' 1 i am e n t

but

virtually

f

(Be I..' i ngton ,

h e a I.! e n

Usually comical Vice figures appear

Drama 791).

plays

0

ar'e not ] i m i ted to them.

every

< Be\! i ngton,

other

Dr' am a

form

of

.Just

7'7' 1 ) •

in moral i ty

IJ ice f i gur·e-:. appear'

medieval

like

as

dr' ·3.m.".

music,

col or'fu 1

They

co:. t um i n g ,

Also,

forms of drama take place "on earth in the midst of an

arena th.". t encompa.sses hea.\!en a.nd

pro i mar',"

The

other

a:.pect.

(Bevington,

he 11 "

di ffer'ence

"Wher'e

the

the

cycles

drama

take

fulfillin';) the totality of huma.n histor:y

cr'ucial

r'hythms,

the

(Pot ter'

,!,).

history

the i r'

2t.nd

on

for'm

defining

an,'

in

its

of

ife

of

the

i nd i v i dual

The mc,r'a 1 it>·· P 1 ·a::.·· te 11,;;, the stc,r'y

of a representative individual

collective

than

moral i ty play takes its shape from a

different figure and pattern--the

be i ng"

Drama

the

concentrates more on the focus of

human

1

the cycle plays the

large crowd scenes, and other features of the cycles.

both

in

1,<Je]

moral ity plays make use of mansion and platea staging.

also incorporate

in

all

play is usual]y named Mankind,

Christian

rather

than

the

men.

or

another

name

evoking

his

Both types of plays,

relationship to all men.

mClr'al and cyel ieal, -=:.eek tel invoh!e the audience member'-=:,

the

dramatic

to provide opportuni ties for them to

action,

"identify

with the characters of the play

may

fully

more

so

The

103).

i n d i '. . i du ali z i n 9

his tor' i cal

plays

c:;.'c 1 i cal

characters,

do

this

whereas

by

the moral

in ter·l udes -;:.tr· i ~}e to un i l,.Ier·-;:..:..l i ze the i r' chara.c ter-:.

O(ahr·l

[they]

that

the nature of the doctrinal message

grasp

pur")eyed" (I<ahr'l

as possible

in

full

:.-:

-'

~,

y

in order to reach every member of their audience

103).

It

i-:. thi-:. str·i'.)ing fClr' uni'Jer·-;:.al i ty that lead-:. to the

use of abstraction-:· and gener·al ized n·:..mes in the play·:;.

mentioned

befor'e,

·:.ome

cri tics

all egor' i ca.l drama call i ng the

ab-:. t r ac t i Clr, -:. ,

today

pl ays,

downgrade

"drama

of

As

t hi·:.

bloodless

of sti lted characterizations, and thus indeed

ani n fer' i 0 r mod e

0

f d r O.m a " <I( a h r' 1 1 0 4).

ace e p tin g ,:. u c h a.

-:.~. . e

Yet be for e

e- pin g g e- n e- r' ali z a t ion

0

r' e ad i 1 y

n e- mu -:. t not e- t hat :

Recen t

rei.) i val s. • • ha~)e rem i nded us, if '. . . e '. . . ere

prone to forget, that whe-ne-ver the- play was acted,

the characters, instead of be-ing dreary types and

ab-:.tr·a.ction-;:., (.\Ier·e a.t once

indil,!idualize-d a,nd

humanized; and the same transformation once

tooK

placein

the case

of eve-ry one- of the other

Moral ities which are now so hastily Judged on

the

basis clf the- pr'inted CCIP~'" (Kahr'l 104).

It

see~T1s

the \)iew that the mor'alities are dully a.llegor·ical

persists because- the plays

acquaintance

only,

pr'clduc t i on .

"Whe-n

speakers"

are

i n·:.tead

one-

re-ads

discusse-d

of

from

such

from

a

reading

fa.m i 1 i ar' i ty'

1..0,1

i th

plaYs,

names down the le-ft margin of the- page- inexorably

7

insists on the allegory through repetition of such names

"'Jor·ld, F'r'ide, cor' Gocllj Angel"

(I<ahr'l

1(4).

ir, productic1n this r'epetition does neat clccur·.

On

Genus,'

~Humanum

HmA.le',.ler·,

stage the actors are

first

a~

infrequently called by name after their

in

except

appe'ara.nce

context of the dialogue.

l.c.I i

1.·<Ja.y·s

th

lh i ch are natur.?-.l

in the

l....

this

in

mind,

i t

be come'S·

to disasseaciate the rigidity eaf the written allegeary

easier'

from the animated actiean of the play.

Characterization is at the very

in

the

e x am i n i rll;l

heart

characters

of

dra.ma,

and

medieval drama one

"should be careful

tea rid (oneself] eaf purely modern notions

of the nature and

function

[One]

cleased,

i ya,j i rna.

eaf

moralities.

l.A.lay "r'ea 1"

not

me t h cld i C a I 1 y

This

96) .

d i 'S·C uS'S. i on

are

characterizatiean.

s h 0 LId e q u .:0. I I y a v 0 i d. . . II his tor' i c a I p 0 sit i I.) i sm" IAI h i c h ,

wi th eyes

(t'1

dr·.ama tic

of

the

The

II

is

clb 1 i t e r' a. t e':·

especially

r' e ali 'S.m"

of

charac ter's ar'e

'S.IJ b,j e c t

relevant

characters

to

"r'ea I

be

"r'e a I "

II

The:)"

in

lack

These

the

in

within

notion that these characters are

i nd i ~.I i dual'S. mu'S.t be ·:.hunned.

mean t

it'S.

any

the

in seame

cha.r·ac ter":.

sense that

Ibsen~s

ps:;,'chol og i ca I

depth.

" the sec h a r act e r' s h.a \,.1 e the i r' m. . 1n " r' e a I i sm ,., but

is inevitably of a different sort" (Miya,jima 96).

Each char'acter

in

the moralities

is

clea.rl:Y·

identified,

without

any

ambiQuity

as a

ster'eot::,1ped be i ng or' an abstr'act qual i t:>/.

Often

the character a.nnc.unce'S· him'S.elf e::<pl ici tly and in

concrete terms.

It is by adding the dimensiean

of

or·d ina r y I i f e

t o t h e per 'S·c.n i f i cat i on s

an d bv

another factor (that of the pre-conception of

the

character' in the ·:.pectator·····:. mind) that the Cl.uthor·

8

II

it

of

the

rT"JCIr'a 1 i b'"

enr' i che-:;.

his

char·",.c ter' i za t i on

(fv1 i :,' .~..j i ma 96).

Thu-:;.,

in clr·der· to

char- .~_C t e r' s ,

one

pr'o',!ide

an

tr'Y'

must

.accur·ate

to

mediet)a1

them

see

In

audience would have viewed them.

account

the

pr-esented

the a. t e r' - goe r-

as

of

the medi

e~!"'.l

mor-a 1 it i e':·

with

five

the

major-

char-acter- types; HumanKind, Vice, Vir-tue, Death, and God.

Al though

un i 'Jer·-:;.e ,

God

"the

was

the

at

Jog i c a.l

center'

of

pr-otagonist of the mor-al

man--never- spir-itua1ly per-fect or- saintly

man--p1aced

in

between good and

fr'eedom

that

choice

of

mor'al

shapes

"man" char-acter- car-r-ies

which

is

emphasized

pI aywr- i gh t-:..

humani ty

by

char-acter"

it

a

most

of

the

of men.

is the play Ever-yman.

r-eason

of

its

(Far-nham 177).

The

r-emar-kable

dual it:,',

medie',!al

mor- ali t >'

often

fr·om

a

man,

The example i1lustr-ating this

Thr-oughout this play the author-

emphasizes the ambiguity of the characterswi tching

simp 1 y

of str-esses and str-ains

wi thin

bv

dr-ama was

bu t

man,

This "man" char-acter- is a man, simply

but also "simply" all

bes.t

wor-ld

wher-e

evil

med i e~·la 1

the

the

sin gu 1 ar'

to

" E~! e r' y'm an. "

the

pI ur'a I ,

the

i n d i t) i du all

and

gener-a.lly.

The se

SI.·'.1

i

t che s

;Of

in number ar-e emphasized

below in God's fir-st speech:

Euer-y.!lliill.. I yueth s·o after' his mvne pI easur-e,

And )'e t clf theYT I ;-"'fe 1.b.ll be nClthynge ·:·ur·e.

I -:;·e the mor-e that I them for'ber-e

The v-.Ior--:;·e the/" be fr'o yer'e to yer·e.

All that 1 ~. . ueth appa>'r-eth f.~.ste;

ThE-r·fc,r·e I v.Jyll , in a.l the ha-:;.te,

Haue a r-ekenynge of euer-y mannes per-sone;

For, and I leue the people thus alone

In theyr lyfe .and I..\»·'cked tempestes,

I.•) e r y 1 y.

the %" 1,0.) ill be c om e mCo C hew CI r set han bee s t e s ,

For· n CIIAI on e wc11 de by en u /. an 0 the r· I.) pet e j

Char::de they do all clene forgete.

I h Clp e d VJe I 1 t hat e u e r· y man

I n my g1or·y shol de mak:e his mans~~·on,

And tt-;er·to I had them all el ecte...

0: 11. 40-54)

When God

summons

Everyman

~e

Death

and

orders

i nth e p 1 u r

·90

l.

to a lesser extent throughout the

It

serves

collective fates.

to

nature manifests itself in

of

being.

play,

emphasize

of

Man

'( e

B.nd

our

f c. r·

in d i vi du a 1

embodies

ethere.:..l

f r· om

and

another

Th i s b i par tit e

placement

in

the

great

inhabits the midpoint on this chain,

the summit of the lower order of being and the base

higher·

with

t (.'..Ih e n De a t h

i -:.

bod:;.-· an d sou I.

man's

return

T his am big u it·:,·· con tin u e s

The "Man" character

t hat

chain

to

speaks of him in the singular.

r· e p lie -:., h e doe s s 0

accident.:..l.

him

or· der· •

His

necessi tated by his body which

placement

on

is "destined to

corruption of death, but his soul

of

the

the chain is

undergo

the

carne only at the moment of

his conception directly from God who created it and destined

it

for· eternal

frees man's soul

soul

flesh.

has

1 ife"

(l'"li::,..-.:..j ima 98).

Thus death of the body

to join the higher order, but only

if

the

been able to win out over the base desires of the

It is thi-:. fight beb.<Jeen bod>' and soul

that

i-:. clften

presented in these plays. The play Wisdom attacks this motif

in perhaps

the

most

char·ac ters

for·

body and

ar·e

obvious

'::.OIJ

1.

pre-:.en ted

way,

bv

offering

In this case the characters

embod i e-:·

10

separate

the

pur·!?

~·ou

1 , i n tel 1 e c t ,

r·ec«.~·on

and

,

represents the soul which

the

rat ion a l.

con~·c

and

i ence;

the

is torn between

The tvJ 0 par'

t~.

Anima,

who

sensua 1

.:<.nd

CI fAn i ma a r' e':· ::im b cd i zed b)/ her'

whi te dress covered by a black mantle.

However',

na.ture,

the

de~.pite

acKnowledgment

of

man's

dual

is held highly accountable for his own actions.

he

No faul t can be blamed entirely upon the body, for the

must

be

a.

pa.rt

of

all

.:<.ct ions as 1,.Jell.

in

ultimate arbiter of action, and

complete

free

will.

the

he

decides his fate.

the

struggle

audience

saw

pla.::.'

it

choice

not

merely

psychomachia,

for the soul of the protagonist conducted by rival

(I{ahrl

their

weaKnesses.

choice

accor'ded

is by his own

these

In~tead,

are

to tluniversal ize the patterns of moral

on

is the

It is impor·tant tCI r'eal ize that

was

armies of good and evil.

I ife tl

is

1

the Virtues and Vices may

Al though

fight for possession of man's soul

that

The soul

~.ou

The

110).

powers

of

de':.igned to

for'ce~.

persuasion

plays

which

choice in man/s

de~.tr·o::,'

man

r'e]';.'·

and trickery and on man's

They can push man toward a

itself belongs to the man alone.

decision,

bu t

the

This is apparent

in

the epilogue by Mercy at the end of ManKind:

Ye may both save and spill yowr sowle,

that is so precius;

'L i ber'e well e, 1 i bere noll e'" God ma.:)··

nClt den::.', i lJ. 1 i ~. ( 1 1. B$';::-4).

This

tran·:lates as,

")'OU

or damnation; God may not

f r eel y

n CI t to c h 00 s e,

ha.ve free v. lill

deny

t r u 1 y"

.::

11

you

to choose salt)ation

freely

to

choose

8 e t,J i n g ton, Dr' am a '7':3 7::'.

or

The s e

plays then, are studies in the choices

oppor' tun it;.'

recur'ren t

tc.

in

fall,

made

"the

men,

by

which man

is no inert

battlefield over which the forces of good and evil march but

a being wi th free wi 1 1

right

the

choose

death" O(ahr·l

created

God

by

whose

chances

to

road to salvation end with the coming of

1(6).

tv 1an·':. fr'ee (.,Ii II

i:. hi:. as:.et

in

these

Although his poor choices lead him to the brink of

pI a>'s.

i :.

damnation, he

acutel~...

a . .·Jar· e c.f the fact the the choice of

salvation (AlaS a 1 ~<Ja:ys possible and could be made up un til

the

time c.f de ... t h .

man . ' .:.

In :·ome ("'Jay:· the focus on

detract

from

the

play

would

(.',1

i t h c.u t them,

disappear,

:.hell of.:co :.aint·'s play.

cruc i 21.1

the

This play begins

pI a.Y.

J.....lor I d,

the

Flesh,

Mankind's fate

()ice:..

ill

se em':·

t c.

and

the

c e n t r .:..1

conflict

leaving nothing behind but the

In The Castle of Perseverance

duty

the

of setting the mood for the

with

the

of

three

vice

De . . • iI,

on

characters,

stage

the

discussing

in much the same way Shakespeare's witches do

in a later period.

the

(-<.I

importance of the Vice characters within

the mor' ali tie:., bu t

the

fr'ee

But a man's fate wasn't entirely

up

to

Since salvation was always possible, the main

task of the Vices was not only to pull man down, but to keep

him down until Death could arrive.

persuasive

Ar·med on 1 y

powers and means for trickery,

to lead man astray.

"Mo:.t of

temp ter' s

only

are

not

the

mascul ine

.-.

1 ..:::..

Deadly

but

(.\1

i th

their

the vices attempt

Sins

and

aggressively

other

so,

boisterous, arr'ogant,

lClud"

camaraderie usually entices Man to join them.

usually

t 0 ken ,:.

0

"opulent

in

presented

The i r'

(Bevington, Castle 161).

f ext r' ·a~) a g ant I u:x: u r' y

They are also

jewels, and other

finery,

(B e v i n g ton, Ca-=:. tIe 1 6 [I).

"

Th e :).

promise Man a multitude of wealth, wi t, and women, and chide

him

for

c om i c .::0. 1

his

0

f

naivete.

In the the play Mankind,

the m0 r a. 1 i tie s,

the i r ,:. h"l i sh c lot h e s ,

Mankind

for

Falstaff

his

and

e·:.t

j

piety

his

the

I)

ice s a r' e

.:o.bout

and

of

in

ma.n >.,

i).

These

transgressions and foibles.

known

form

of

,Ior·k.

Like

the /.

ar'e

of churches"

characters

provided

Their

into lau9hin9 at their own

characters

for their rapport with the audience.

They serve

of Lucifer

fact that he

them

at

vice

to involve the audience

the

jeer'

the centr·.al entertainment.

V.Ja.ys

raucous ways cajoled the audience

are

h 0 f 1 au n t

1....

da t e ,

despoilers

vice

I..V

and

to h.ar·d

1 ate r'

and

(Bev i n9ton, t1acr'0 :x: i

r' 01.....1die s

hangin9,

devotion

companions

hi9hwaymen,

II

the most

In fact,

in the play.

the

A

vice

plan-=:.

f i gu rei s Tit i \. i I Ius.

1

audience while he

in

in Wisdom shares with the audience the

is not the gallant he seems to

hi-=:.

character

(1.

324) .

be,

and

te 1 1·:.

In Mankind the major vice

In the play he remains visible to the

is invisible to Mankind.

Ti tivi llus' cronies lead the audience

in

I nth e':· a.m e pIa :,.

singing

and

also

take up.a ccollection befor'\? the play's climax.

Just

as the vices could not force their ways upon Man,

neither can the virtues.

The seven virtues in

13

directly

"serves

')ir-tue

the

oppose

as

seven

a

Each -:::-er-mcln by -:;.

Deadly Sins.

remedium

the

for

lessons

of

the

appropriate vice, and together they bring ManKind to a state

in

which

he

can

(Sche 1 1 2:3::::).

the

I.)ice-;:-~

the Vices,

receive

God's

Not on 1 ~.-- do the i r- doc tr- i ne-:-

c i r-ec t 1 :~'

oppcl-:-e

their manners and costuming do as well.

Un1 ik:e

the Virtues who aid

Per-se'-}er-ance are

"10\}e1y

as

the

opposed

grace--if he perseveres"

to

in

Mank:ind

The

"robys rounde" and "grete

extravagant

-:;. -:- "-:- e \) e n e -:- i -:- t e r ~.' -;:-

-;:_~\I e

t e"

(1.

The::.'

"bicct-i:;"-:_"

should not be

-:-er-mon-:-

The

between the Vices and Virtues is heightened by the

Vices' description of the sisters as

and

a_roe

20 47 ) and -:;. r- e a 1 -:- 0

1764, 18(6),

refer-r-ed tCI a-:- "ma i d::.'ns" and "1 a_dys" (11

contrast

of

in 1a_ce" (1.2254:3), simp1:-;- dr-es-5ed

gounse" (11. 2072-73) of Pr- i de and hi -;:- cohclr- ts.

de -=- c r- i bed

Castle

<11.

seen

1728-31,

as

of the I.) i r- tues,

dull

"'--\Ienchys, "

1 :384).

didactic

1 i k:e the

i n t r u s ion sin t CI

2:3'7') ,

intr·icateL.'

inst.ead ar·e

:~--e

t,

the I..) i r- t u e s

characters.

"The

i nstr-uc t i cln-:- of the Dead1:-;-

Sin s, a_ r- e not h om i 1 e tic

but

An d

"mo derys,"

l;..lo~Jen

the

pl .... ::.' "

(Schell

into to the

p1a~.,···-:.

ac t i on •

Quite often, as is the case in psychomachia,

and Vices go against each other in one to one

The Castle of Perseverance an all out battle

Vices

c omb-~_ t .

In

is waged as the

attack: the Castle in which ManKind has sought refuge.

Wrath goes into battle intending to use

hoping

the Virtues

to pelt Patience

"~"Iith

14

his

cross-bow

and

stiffe ston:y·s" (11.2111-12).

Envy intends to

inflame

attack

Charity

while

hopes

to

The Virtues go into battle armed only

Abstinence.

with Scriptures, flowers and water.

is

Gluttony

This Christian

paradox

heightened b>' comic incongr'ui t::,t as· the c'I}er·tl::.·· mas.cul ine

!.)ices wince

received

in pain and humi 1 iation

from

such

passive

the

.~t

.IOunds they

weapons.

is.

A:·

moment

free

Mankind~s

wi 1 1

u-:.ua I the

.;:.. t

Ye t

Virtues, with their meeK way, win the battle.

cr'ucial

ha.',.le

1....

interferes

the

with his

salvation as he chooses to go away with Covetousness.

A Ion 9 the s. am e l i n e':;· as· the Iv' i r' t u e -:., but per' hap s·

higher

plane

These four characters appear

of the rrror·a.l it i es, but .:;'.r·e

scene

of

Justitia

et

each clther':

most

effect i vel:)I

used

II

1 i ter.:;..1 i zes the

~Misericordia

1..~le

in

Justice and Peace

The stage

1 i nes

1 1 -knQl..~ln

et Veritas obviaverunt sibi;

hal}e

k: i ss.ed·')

(Bevington,

II

In the scene Truth and Justice argue against

Mankind/s salvation,

defense.

In

the

while

end

Mercy

Mercy's

and

Peace

provide

According

into

at

his

to the stage directions for the play,

these daughters are dressed in colored cloaks

gr'ouping

his

arguments win God over to

Mankind's side, and God invi tes Mankind to join him

their

the

Pax osculatae sunt' ('Mercy and Truth have met

Castle

right.

a

in several

The Castle of Perseverance.

ac t i on dur i ng th i -:. scene

from Psalm 84.11,

n

the four daughters of God; Mercy, Truth,

are

Peace, and Justice.

eli mac tic

0

two

opposing pairs.

wear white and black while Truth and Justice

15

to

s.ymbc11 i ze

Mercy and Peace

wear

red

and

LiKe the

gr·een.

these daughters of God are unable

Virtues~

to maKe man change his ways.

1'"1er·cy

doe=.

been taKen

strictly

·:::.tr· i c t

(a=. a male)

a

accordance

man

and

chance

~

else has

a

ma.tter·

This theme runs in

the

theol og i c.:.. I

plays

be h .... een t"1an and his god.

a

role

a deathbed confession away.

moment of death.

Ii·!

i th

pauper, Knight or knave.

the

2t.=.

Because of

this~

his

Eternal salvation was only

What Man put odds

on

was

his

ittle regard toward salvation.

No

one

was safe, prince or

During

the

Middle

roared

across

discriminate.

dom ina. ted

this relationship

Yet Death himself paid little attention to

the odds and took I i \)es

didn't

in

1'"1an knel}.! tha. t he had up un til

moment of death to repent.

Death

as

period.

Howeve r'

very

his god.

the

IAii th

prod

Even when all

t···lan~~ind.

into consideration, salvation is sti I I

between

medieval

in

They can only gently

plague

Ages

Death

the countryside.

the personage of Death on stage would

send

a chill

through each member of a fifteenth century audience.

Theirs

wa=

an

in

manifests

age

the i r'

i tse If

preoccupied with death, and this comes

dr·ama.

mor'e

the

in the fact that the plays exist at

all

than in the char'acter'ization clf Death within the

In

fact~

in

only two of the Engl ish moral ities does Death

appear on stage; Everyman and

(M i Y·:d i rna.

pla>'=..

109).

As

a

The

Castle

of

Perseverance

whole the plays tend to emphasize

lurks

16

nearby

and

the wages of sin is indeed eternal damnation.

In

qu i te

'5

im i I ar

appear·ance

In

two

the

The

plays

(1'"1 i

)/Ci. .J

the characterizations of Death are

i rna

10':;0;..

In

mor· e r· e IJ e r· e d •

of

to

" If, f r· om the p CI i n t of dr· ama tic

in

Dea. th

t han

Death

.:..pp e c..r·"S.

at

(1·'1 i ::•.. a..i i ma.

imp ·:..c t,

has

left

the wi les of Covetousness.

the

in ter·ven t i en

plague.

( II.

2815-

the .:..p p e ·:..r a.n c e

beginning

i "S.

of

Ii mi ted,

In

10$') •

i mp r· e "S..::;. i

t)

e"

occurs at the moment when ManKind

least expects it, .Just after he

to

Knowe"

i t r· ern.:<. i n"S. n e 1,1 e r· the I e"S· .::;. qui t e

109).

succumbed

the

of

The Castle of Perseverance is less remarKable

i n EI.) e r· ym a. n,

(1'"1 i ya..i i 1Ti.8.

indeed the

the blacK death point to this (Miyajima 109).

"In the grete pestelens/Thanne was I weI

of

DeCi. th·'"S.

i"S. sl ightl)···

This le·:..d·::;. to the r·eal ization th.:..t

that

=.

ct'·liy·:...jima 109).

Per·se\)er·Ci.nce it seems death

play is from a period much closer to

16) •

C .;:t..:.€-

i·::;. "br·ief but ·::;killfull>' managed"

CCistle

Allusions

both

i t

t hi .=.

the

i·::.

c·:..·::·e

play

the

Ca"S.tle

.:..nd

In Everyman Death

and

cruci.:..l

"whi Ie

his

dr· ama tic a I I y"

manner·

i·::;.

·::.tra i gh tfor·'Alard and pr·.:..c t i cal.

His approach

to Everyman

is peremptory.

The

speech by 1..~lhil:h he

intr·oduces himself

j.=.

a

masterpiece of forceful concision.

He tells the

audience he is omnipresent and that he cruelly

pursues the great as well as the humble of the

earth

and

especially

the

rich

and

the

concupiscent.

He exploits Everyman's

initial

sur·pr· i se b:;·· reca.11 i ng God and gi 1,1 i ng Et..'er·::..-rn.:..n

pr·ec i"Se

i n"S.truc t i on

in .a I mo·::;.t mil i tar·y f.a"S.h i on.

'Therfore

thy boKe of counte with

the

thou

brynge,/For tourne agayne thou can not by no waye'

(tyliY.:<.j ima 110).

Death

continues

by

scornfully

17

refusing to be bribed.

He

deals severely wi th Everyman/s tears,

messenger of

covering

then

He

God.

proceeds

insists he

upon

we

see

"I f IAle ana I yze

on the one hand, and the doctrinal

the ars· mor'iendi

The

last

on the other"

form

chain

of

world rotated.

He

force

aI d

being,

Grand

T est am e n t

(l'·li:~'a.jima

110).

point

ima9inin9, for example,

of

man

I il-';e

<•.1 e

their

God

on

of

On one hand God was looKed upon

n9e f u 1 ,

omnipotent, overpowerin9

On the other hand He was reduced

" .' Th e : . .

.j u dge , . '

I. . .!r' 0 t e

the

analogy

of

." II

1a I t e r

century

stage

Bibl ical sanctions a9ainst such

in

the

/of

corporeal

that God in his own nature

their' o(.o.)n, ... '

to

1." •.

0"1

has

i ya.j i ma 106) •

explains why the people of this period felt no qualms

putting

the

in history the concept

Hilton of his contemporaries of the fourteenth

fr'om

of

the center upon which the medieval

anthropomorphic.

thing':;

Leveller

and homiletic aspect from

Yet at this point

in the universe.

somethin9

the author' had

i·::. the culminatinl;::)

God was in a state of flux.

the

of

of characterization to be found in the

plays is that of God.

as

discourse

the speeches.

i n a fev,1 dozen lines.,

how,

brought in the popular concept of Death the

great

a

is the

Original Sin and the Last Judgment. He then leaves

as suddenly as he appeared.

Death,

then

mor·a.l it i es

imp e r' son a t i on s· .

the

This

about

desp i te

I t

a

1':.0

explains why no elaborate special effects were needed by the

God

character

since

the

people

omnipotent even thou9h he moved

<-.

I e.

r'eal ized

about

in

God

could

be

mor ta 1 ma.n.

Th

dua 1 i t::,1 in the na tur·e clf God man i fested i

i~.

the st.:..ge a.s

~",ell

In

•

of God is exempl ified in

God

appears

God

~etween

The

God

Castle

as both the

Mankind/s actions and as

contrast

plays

often

formi dabl e and the mer'c i ful.

the

which

the

God

of

Th

i~.

d1J3.1

merciful

on

natur'e

Perseverance,

as Judge and God as Father

in

Judge of

Father.

ife hangs in the balance.

in

1f

vacillated

intimidating final

the

t~.e

The

is stark,

HOI..'.Ie~Jer

,

the enc gentle prodding from Mercy causes God to embrace

his fal len son,

saying~

My mercy, Mankynd, yeue I the.

Cum s~t at my ryth honde.

Ful wel haue I louyd the,

'..)nK::r'nc thm·,1 I the fonde

.: 11. 3598-36(1).

Yet t hi,;,

of the

~.

h C'[A.I

pla~

0

f mer' c ),- i -;- c 0 u n t e r- e d by h i -;. 1 i n e';· .:.. t the

end

in which he offers a final warning:

& thei that weI do in thys werld, here welthe schal a wake

In heuene thei schal heynyd in bounte and blys

thei that evyl do thei ~.chul to helle laKE'

In byttyr balys to be brent my Judgement it is

t-"1;..- '.)er- tus in heuene thanne ~-cha 1 the i ql.J.Jal(e

ther is no wyth in this werld that may skape this

all men example here at may taKe

to mayntein the goode and mendyn here mys

ex

thus endyth oure gamys.

To saue you fro synnynge,

Evyr 3t the begynnynge

Thynke on youre last endynge '

De ~-p i te

sermonizin~,

~.aving

[.'.Ii th the

the

fact

their

( 1 1. 3638-48)

that sometimes the plays lapse into

the-"dr- i ca.l i t~.--

all,\la/-s

-:;er-I.}es

a.s

the i r'

pub1 i c

speaYer---

9r·ace.

e~,Ie

of

a

sk ill ed

preacher'

1 ~.

or-

balancing rhetoric and earnestness against an awareness that

the

audience

mousetrapped into

the

play:.

re lief.

()er·ba I

de I i gh ted

(Potter 33).

understanding~

the

IJ:.e

and

·:.urpr i :.ed

be

mu:· t

To

.",nd

do

this

effects of low humor and comic

However, much of their theatrical i ty comes from the

Often

visual effects of their staging.

used

elaborate

the p I

a~...

pageantry

times

these

plays

and costuming as is mentioned in

Wi:. d om :

Fyrst enteryde WYSDOME in a ryche

purpul I

clothe

of gold wyth a mantyl I

of

the same ermynnyde

l.<J::.'th in, hawynge abouwt tn's neke a r·ya I I hood

furred wyth ermyn, wpon hys hede a cheweler wyth

browyyys, a berde of golde os sypres curlyed,

a

ryche

imperyall

crown [thJwpon sett wyth precyus

:.ton~.··:, .:t.nd per'l :.':....

(Potter' 34).

Other notable costuming effects are apparent in the

Virtues

their virginal white robes and in the Vic@s with their

sumptuous finery.

the

r' e p r' e ·;:·e n t

Changes in costuming

various

stages

of

are

Man.

represented in The Castle of Perseverance.

this

play

representee

Mankind

is

by an actor

found

also

naked

used

to

Th i:.

At the beginning

and

newly

in flesh-colored tights.

born,

This lack

of ear'thl>' clc.thing r·epr·€'·:,ent·:. hi:. initial pur·ity.

Once the

Vices appear in their finery Mankind becomes concerned about

hi:. appear·,:.nce, .3.nd ·:·oc.n he,

At

v,)

0

this

point

n de" and i n

reI iance

~

one

can

too,

ob':.er'~.'e

r' 0 b : ." .:. r' i'.) e" (I I.

.~.

upon v.,lor·ldl:y· plea,,:.ur'es.

is. dr·e·;:.:.ed in the fu 11

i,;:, dr·e·;:.:.ed

he

a<=·

is clothed in

2 5, 6'7' '7'), a ':. a s i g n

~1.AJelth:Y's

0

f

hi·:.

Later, before he dies, he

loo';:'€' r·obe:· of .:t,n c.l d man.

20

.3.re.

the~.··

"Stage

epochs

1 ike

properties,

costume

changes,

the career of ManKind as he oscillates from good

in

toe ',) iI, an d g i \) e can c r' e t e thE'.;c. t r' i cal f or'm

homiletic

metaphor"

to

can ',! e n t i on a 1

(Be'. . i ngton, Ca:.t 1 e 162).

For E'xample,

the "pricK of conscience and death",:. dart ar'e

to

Juxtapose

is

the plays;

al iKe

ife of

The prick of

qu i te 1 i ter'.:..ll ::,', as .:O.r·e a 11 .;c,c t i on:·

taKen

thus,

enough

two cri tical moments in the

visually

the protagonist" (Bevington, Castle 162).

d.;c.r ts

the

mark

thE' major prop USE'd by both

the

t_~1

i th i n

Penitence

and

Death is a lance wi th which to pricK Mankind.

Props are used also in the battle between the Vices and

I.)

i r' tues.

Gluttony attacKs AbstinencE' with a flaming torch

Lecher'::.--,

(1.15'61).

too, battles. t",lith fir-e, but is r'epelled

by Chast j t:;;- t/Jho quenche:-

II

th.:O.t fOl..'.,Il e he tE'"

0:

Sloth

1. 2:30:3).

proposE's to drain the moat surrounding thE' castle by use

hi·:.

f

sp a.de

(11.

2326-29).

Use of fire abounds as the smoke

r' om "h ell fir' e" r- col 1 s· for' t h f r- om the s· c a f f old c' f

who informs ManKind that there he will

(11. 32076-7:=:).

The

Virtues

burn

banners as do thE' Vices.

rages the Vices can be identified by their

including

lances,

f i r·ebr·a.nds,

and

conversely, fight armed wi th flowE'rs

in

natur·e.

As the b.:O.ttle

weapons

Th e

shields.

and

the de viI ,

in pitch and tar

tvlan::.' of the pr·ops. ar'e mi 1 i tar',,'-

raise

of

water

to

of

t.)

war

i r' t u e -:. ,

quench

rage B.nd hatr·ed.

tvlu ';:. i c ,

plays.

too,

is

used

to

heighten

In many of the plays trumpets are

21

the

impact of the

used,

e sp e c i .;c. 1 1 ::.'

in

battle

In Jhe Castle of Perseverance trumpets

scenes.

are called for by Bel ial who commands, "Clariouns cryith

-3. t

k r -3.k e" (1 1. 2197).

.;:t.

of

Mankind

A 1 so mu sic ''; i gn.::<. 1 s the

t..·.1

inn i n go\.) e r

Thi·:. is. cc.unter·ed later' in

to the side of sin.

the play when the Virtues sing to celebrate ManKind's

i n tot h e c a. s· tIe •

up

entry

A t the end a fin aIm u .:. i c·::<. I pie c e i s calle d

for by God, the Te Deum laudamus.

.Just

ev iI,

SCI

befor'e,

as costumes, props, and music del ineate good from

do the gestures of the charac ter·s.

the

Vices

As

men t i oned

are rowdy, raucous characters, loud and

boisterous, while the Virtues are meek and retiring.

the

Vices

shout

and

laugh,

the

Virtues sigh and cry in

lament for Mankind's wicKed ways.

Yet this is

the

and the Bad Angel

and

end of Castle when the Vices

"s~~'e

klh i Ie

reversed

at

"sobbe"

sore" (11. 1866, 3593) as t"'1ank i nd stands befor'e the

throne of God and they "are beaten down to

hell

[. . Ih i Ie

the

virtuous rejoice" (Bevington, Castle 168).

The

the most

last element of staging to be discussed is perhaps

important one, scenic practices.

the plays follm\led similar' de·:.igns,

Castle

the

0

of

Al though most

of

the s.ta.ge des.ign for' The

Per'severance is the most el.::<.bor·.::<.te.

AI':"::',

it is

n l~... Eng lis. h mc. r' a lit y P I a::,' t 0 c. f fer' an e :x: t .: <. n t d i .;:t. g r' am

the "stage" design (Appendix II).

0

f

For this playa castle is

erected in the center of the platea, or playing space.

This

playing space was outdoors since around i t a di tch was

dug.

This

ditch

had the dual

purpose of serving as the castle's

.-, .-.

Li:..

moat and also the means by

The audience gathered in the area between the

sp e ct·;:.. tor' s •

castle and the ditch.

On the

outside

or "mansions" were built.

sca.ffol ds,

belonged

to

Bel ial,

nor·thea.-:.ter·n tCI

imagery

out

which

the

the

as

was

Fle-:.h,

and

the

scaffold represented Heaven whi Ie the

These

western scaffold represented Hel I

decorated

f i ~.!e

As is appropr i a.te to Bi bl i cal

CO~..Ietousness.

Eastern

di tch

The northern scaffold

tCI

-=:·ou thern

the

of

their

to

appropriate

scaffolds belonging to the Vices were

scaffolds

were

occupants.

The

richly

arrayed,

the

hell scaffold was designed as a "hell-mouth," and the Heaven

scaffold

was

i t·s g I or y mo t if.

in

resplendent

performance the action moved from one

and

so

did

the

audience.

scaffold

Dur'ing the

to

another

"In such a cosmic arena, stage

mol,.' eme n t c a,n not fa i Ito -;:·u gge s t a ·:.e n se of d i r' e c t i on or'

opposite,

wandering,

in man's spiritual pilgrimage through

I ife" (Bevington, C.::o.-:,tle 1(0). Thi-;:. r'esIJlt-=:. in

a.c t i on, on e I.) e r' tic a I, on e h or' i z on t a I.

the

\.-' ice -;:.

into sin.

a -:.c end-=:o •

r"j a

r, ~:: i n d

When

goes

This

e a. s t t CI

into

plane-=:. of

Af t e r h i -:. vis i t

lit e r' all /' f r' om the s c a f f

the

castle

to

repent

t.o,1

ith

0

I d::O

he

movement

changes

to

ascent

yet

as mankind mounts the Heaven scaffold after his final

repentance and death.

moves

0::

h'JO

When he reemerges into the grasp of Covetousness

he descends again.

again

des c end -;:.

he

i t-;:.

horizontally

~~, e

The action throughout the

play

also

as Mankind journeys bacK and forth from

-: t, f r' om He a~! e n t

0

He I I, and b a c k •

emerges o~.Ier·al J is a

theater·

repr·e·:;.entat i ve

of

the d i'.) i ne un i 'er·-:;.e,

l~.I i th lit tIe t·'1an at

i t-:.

center and with vast

contending forces facing

their

opposite numbers on every side.

The

audience

is

everywhere

at

once

and

thus

omniscient;

nothing that Man does escapes notice,

his smal lest acts are cosmically significant.

The

audience, sharing the perception that Man's

trust

i n ~~Ior I dl y pr·osper· i t)-·· is ill usor·::,··, i·:;. pr·epar·ed to

c c.n cur· i nth e .j u -:;. tic e of the fin.:o. I .j u dgme n t sc e n e ,

and to apply the lesson to its own need

to

thinK

on the "end i nge da>'" (Be'v' i ngton, Ca-:.t Ie 170).

~·Jh20.t

I•.•

In plays not as scenically elaborate as Castle the same

principles hold true.

basic

These plays usually begin wi th

a prologue by a speaker, either a character

for·ma I

In

p r· e -:·e n t e r· •

.:o.c k n m. .11 edge

the

t hi·:;.

~··.la ::.'

i·::.

freel;.,,·

the

presence of the audience.

not asked to imagine a fictional

spea.ker·

in the play or a

liKely

to

1 oc a Ie,

The audience

ar·e·:o. ,

normally

a

a. r· e

"The pr·ologue

local it::,. of performa.nce.

The

marKet square or guildhall

become for the moment a model

au die n c e

the

allude to the pla;>··ing space itself,

I ikening it to the greater world (Potter 32).

es.t.:o.bl ishe-: the dual

i nste.:o.d

bu t

is

of the world.

not so mu c h a -:;. KEo d t 0

as invi ted by the actors to

-:. u s

pIa.)'·

or field,

Members of

i ng

had

the

pen d the i r· dis. bel i e f ,

to p,o..r·ticipa.te in a

theatrical

analogy" (Potter 33).

I pray you all give your audience,

And here this mater with reverence,

By figure a moral 1 playe:

Tt-Le Scmoninqe of Ever·yman called it i-:.•.• (II

1-4)

Here shal I you se how Falawship and Jol ite,

Bothe Strengthe, Pleasure, and 8eaute,

Will fade from the[e] as floure in Maye;

For ye shall here how our heven Kinge

Calleth Everyman to a generall reKeninge.

Give audience, and here what he doth saye. (11. 16-21)

24

To force the audience to thinK on its own

is

~endinge

indeed the point of each of these plays.

plays

were

designed

to

teach

while

entertaining

didn't leave their audiences with the bitter

public

which

in the end

the

~produce

i-::.

aftertaste

It i·::. impor·tant to note that a

chastisement.

be i ng-::..

to

call

for

repentance

must

It must define human beings as creatures

attr'acti~)e

of

pla:~"

fir·-::.t

c omm una. 1 a. c k n 0(.<.• 1 e d gm e n t t hat \. ..1 ear' e a I I hum a n

the pleasures of the flesh wi 1 1 always seem more

than the con·:.ideration-::. of E'ter·nit;..·~

In other words,

d.n

their

They were communal cal Is to repentance, yet they

.:..ud i ence .

a'::.

day~

for

whom

immediately

(Potter'

the plays view the fal I of each man

::::.~.).

into sin

ine'Ji table par·t of I ife and thu-::. u:.u.:<.l h' :.pend little

time dea.l i ng . .0 i th the concep t of innocence.

example,

begins

when

Everyman

is summoned by Death, long

.:<. f t e r' E ,,) e r ;"m an" sin i t i .:<. I f a I lin to'::' in.

is always saved from damnation

for

y' e t

in the end.

the p r' 0 t .:.. g 0 n i s t

To

t e d.C h

the

means by which sinners can gain salvation is at the heart of

the dr·ama.

Th e mor' a liz i n g of the mor' a lit i e s· i -::. n G t, the n, a

pur i ta.n den i a I of hum.:..n na tur·e; indeed,

it

is .:<.

dogmatic proclamation of the Adam in al I men.

And

fortunately for

all

men,

their sin may lead to

remorse,

that

remorse may

be

converted

to

contri tion,

and

thus they may be forgiven and

s.aIJed. The dialectical the·:.is. of the mc,ral itie-::.,

stated briefly,

is that God has recognized human

nature and carved out for it a path to salvation,

through repentance (Potter 49).

I

nor' der'

to teach this lesson the play must encourage

its audience to "acknowledge wi th laughter [its] recogni tion

of the common weaknesses of humanity,

which

It

can scarcely be blamed" (Potter 36)

the

mor.:..l it;.··

gu i It.

play

ini tial

" Its.

that

pretension

ser·'.}es

any

as

1

attack

human

members

ar·e

"subtly

unpleasant

(Potter·

prepared

to

being

car i c:.. tur·e

When

c,f

that

1.90,.·

1.....

from i nd i v i dual

h::.··pocr· it i cal

the

can be strong enough to

In this

way

its

as

the

own

the

accept

consequences •••

~:6).

on

general

the

a.udience

into accepting their own weaknesses and

I ur·ed

are

i·:::. in th i s·

i ber.:t. t i on

is

resist being human" (Potter 36)

being

un for· tun a. t e

and

a case of collective guil t"

audience,

behavior,

f r· i gh ten e d

sees

the

the

b;.-·

consequences

brought about by the actions of "Mankind" on the stage,

solution

of

repentance

"collective response

i n d i v i du .901

esc ape

to

from

will

an

become compe 11 i ng, both .9oS a

i

n d i t) i du a I

gu i I t

.9ond

the colle c t i ~J e g u i 1 t"

as

during

the

an

(P 0 t t e r· 36).

And if for any reason the audience missed the point

play

the

of

the

action, an epilogue was presented to spur

their consciences.

Gr·anted,

the mai n pur·po-::.e of the mc,r·al it i es· [.<Jas to

individual souls, but perhaps beneath the surface

intent

to

save

society

through

Richard Southern points this out

fr·om

the

gr·ea t

bi bl i cal

imbedded

which

foundation stones of the drama, we find

constant

i es

the

social satire.

stating,"'In

cycles

s· .... '·. 'e

f

were

that

·9oc t ,

apart

the

ba·:::.ic

there

1.....1·:..5

a

incentive to tel I audiences not only something new,

but i f P 0 s· sib 1 e .:. om e t h i n 9 s t a. r· t lin g.""

0"·1 i : ... ·90 jim a. 1 1 7) •

Light

s..:dire is pr'e':;ent

soc i al

in se'.}eral of the

Wisdom jabs

denounces clerical misconduct.

1 a.I . <)

including

satire

at

perjury, false

bribery,

the

unjus.t jur·ies.•

pla~.,s.

deeply

most

abuses

of

indictment and

rooted

social

is contained within The Castle of Perseverance.

This

P I a)'

appears to be a straightforward account of the

perils of the World, the Flesh,

and

the Devi 1-unt i 1 (" . Ie r'eal i s·e that the 1..'•.Ior··::.t of all the deadl y

sins is not shown (as was usual) to be Pride,

but

Covetousness.

Now this may not startle us; but in

a period when the mercanti Ie classes were rising

at the

expense

of

the

old feudal

order,

and

England was finding a great new prosperi ty through

trade,

it must

have

been

in many quarters an

unwelcome doctrine (Southern in Miyaj ima 117)

As one can easily see,

the moral ities were so much more

Gr·a.nted,

than merely "bloodless abstractions."

was allegory dramatized, but that

)'ield

or'

equal

itself does

not

dullness or rigidi ty as some cri tics would

I nstead

oppo·:. i te .

in and of

the mor'al it)··

8 y dr' am a t i z i n g

.;:<. 1

the

effec t

1,,·.Ia.s

leg 0 r y the m0 r' a lit y

qu i te

the

"0 pen

e d up

tc. the dramat i c author'

in Engl.:r.nd the gr·e.:d pos.si bi 1 it i e'::· of

personification as an

instrument

idea'::, .

It

for

presenting

abstract

is. this. technique, much fr'eer' .:r.nd intellectualJ>'

str·onger· and (.\.Ii th mor'e fl e::< i bl e pos.s.i bi lit i es th.3.t s.epa.r.3.tes.

the moral ity from the miracles and mysteries" of

time

period

(Miyaj ima

4-5).

tha. t

The mora lit i es r'epr'esen t .:r.

9r'eat s.tep fc.r·(J..Ia.r·d for' Engl i s.h dr··:c.ma and 1 i ter·a.tur·e.

The author' of ·3. mor·a.l i t::.-· c.:c.n arr'ange

hi':; subject

freely, attempt construction and unity.

He is led

to

analyse

human qual ities and defects,

to

...·-I~

: ...

·::·ame

emphasize

psychological

characteristics.

t'"li ~.er·l i ne~·s,

for'

i n·:.t.::c.nce,

cannot

be pr·e·:.ented

(.'•.1 i thou t

stu d;. .· of the c h a.r· .:r.c t e r of the m i ':;e r' .

In

this

1••'Jay

the

mor·a.lity,

e'·,'en

the r·eligiou·:.

moral i ty, prepared drama for

emancipation from

r'e 1 i 9 ion.

I t~. theme i~. the ~.tr·lJgl~l e of the for'ces

of goc,d an de'. . i 1 !.-'.Jh i c h con t e':· t for' the h IJman sou 1 .

This problem continued to confront the poet who

was no longer inspired by

the Christian faith.

The

permanent

basis of every dramatic worK had

been discovered

(Emi le LegolJis in Miyaj ima 5).

28

APPENDIX I

Th e Le g CI.C 7' of the t'lor' a lit ;~.

Durino

the

sixteenth

underwent several changes.

became

almost

entirely

the

century

mor'ality

f or'm

In some cases the subject matter

secular,

If

in

3.'::-

John

SKel ton's

t'1agn i f i cence, \A.lh j ch descr' i be'::· the Ii fe·::.t::,"l e .appropr i .::..te to .;:..

ruler, or

in Nicholas de la Chesnaye's Condemnation

Bangue t,

\.'.Ih i ch

warns

especially

(Br'ocKe t t

141 ) .

treats

both mental

against

~Perhaps

pl.;:..:)':. is ,John B'::'.les·"s King ,John,

ruler holds

(Br'ocKe t t

out

141).

of

The plays were also often used as weapons

i nth e r' eli g i ou:. ba ttl e:· of the da;.'.

these

the

and physical heal th and

danger·s

the

of

against

the

e\)jl

the

best

of

in 1..<.Ihich the Engl ish

for'ces

of

This play, marKed by historical

'::'.nd E",Jent:. i nter·mi ngl ed into the mor'al i ty

for'm,

the

pope"

personages

1 t?ad:.

the

way for the chronicle plays of ShaKespeare and others.

More

beh<.Ieen

denounced

and more often though,

Protest.::..nts

.;:..nd

the plays marKed divisions

Cathol i cs.

each other in their plays.

The

Protestant playwright

Thomas Naogeorgus penned perhaps the most forceful

of these,

a.1 mo-=:· t

Cover

: . . e ar' -=:. ,

1 ,000

ending

glorification of Luther as a major target

forces, epi tomized in Bishop Pammachius"

HOI.'.)e I} e r' ,

man::.'

these

of

an tic h r' i,:;, t

.:<.ga. in':;. t

Pammachius, "which treats the

I a. ter' ,

with the

.:<.n tic h r' i s t i an

of

<BrocKett 142).

theoreticall/

more

advanced dramas have fal len by the wayside.

Par·a.dox i call y,

in some ways seems simple

in comparison to

Ever'y-man,

I.J.Jh i c h

some of the later plays, stands now as the perfect

the

.~.ge-

It has had a long and successful

•

modern stage, and has exerted

(Hurt 1547).

dr·ama.

moder'n

ceonsiderable

marK

eof

history on the

influence

upeon

The play was restaged in Londeon

13e r'man

Re i nhar·dt

d i r'ec tor'

pr'oduc t i on.

1911 •

It

Reinhardt's Jedermann was

del}e I opmen t

(Hurt

b::.··

the

Leon don

first

in

is apparent that EverYman, along with other pre-

r' e a lis tic ct r' am a':.,

a-=:. a mode I

i nsp ired

i..I.J.:" S.

of

for'

"h a -:;.

had

.:.

t r' 0 n 9

influence

upon

the

the post-r'ea list i c moder'n dr'ama, espec i a II : ..,

dr' am .:t. t i z i n 9

Per·h.:<.p·:.

154E;' •

d.

inner' ,

though,

moral ities too closely wi th

the

it

P':::"'chol Ol;li cal

.:<.ction"

is e;< tr'eme to

ink the

modern

thea.ter.

It

i -:;.

hm'.Jever·, due to it,:. adaptabi Ii t::.-· tha.t the for'm h.::..s sur· l. . i l}ed,

"since

it·:

ba-=:.ic

eventual recovery

(Bel.}ington

795) .

plot

of

-:;.ou l-,:.tr·uggl e,

could

be

su i ted

and the

coun t I e-=:.·:.

themes"

As Bernard SpivacK proved in ShaKespeare

and the A I I ego r' :~.,

-=o,-,f_-=E:..:~._I=-i.:...1 ,

moralitie':'

pr'o l} i ding

for'

to

f aI I ,

Sh .:<.1< e .:.p ear' e

0[....112'

d

mu c h

to

the

in':. i gh tin tot hen a t u r' e clf e I. . i I .

30

"Pichar',j III,

I a 0;;10 , Edumund (in King Lear'), and to ·:..n extent

Falstaff, all

owe much to the Vice as a

mor'al

it~.'

pla~.,-:.

stage

type.

thu-:. became the chief dr·am.:..tic 1 ink bet . . .Jeen

the medieval stao;;le and the Shakespearian," and at

if

left

The

not

in and of

i t·:.e 1 f,

in

the mc,r'a 1 it)' P 1 .:..~.' ha.-:.

its distinctive mark on world theater (Bevington, Drama

31

APPENDIX I I

IIDtlft'~t

UVtt6J<SfIlH

S'4ff~"

This illustration comes from

Will iams, Arnold. The Drama of Medieval England.

University Press, 1961. 150.

32

Michigan State

~~orks

Ci ted

The PI ay';

Anonymous. ~veryman. The Norton Anthology of Engl ish Literature

New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1986. 346-365.

Anonymous. ~ankind. Medieval Drama.

Company, 1975. 903-938.

Boston: Houghton Miffl in

Bevington, DClvid, ed. The Macro Plays.

Corporation, 1972.

Eccles, Mark, ed.

1969.

The Macro Plays.

Ne~\)

York:

,John~.on

Repr'int

London: Oxford University Press,

The Sources

Berthold, Margot. A History of World Theater.

Ungar Publ ishing Co., 1972. 301-34.

New York: Frederick

Bevington, David. "Man, Thinke on Thine Endinge Day: Stage Pictures

Of .Just Judgment in The Castle of Perseverance." Homo,

~1eme!jto Finis.

Ed. David Bevington. Kalamazoo, t1ichigan:

Medieval Institute Publications, 1985. 147-178.

Bevington, David, ed.

CompanY,

1975. 75i l-963.

Medieval Drama. Boston: Houghton Miffl in

Brockett, Oscar G. History of the Theatre.

Inc., 1987. 139-143.

Boston: Allyn and Bacon,

Hurt, James and Brian Wilkie, ed. Literature of the Western World. New

York: Macmillan Publishing Co.! Inc., 1984. 1545-68.

Kahrl, Stanle'y ,..T. Tradition clf t1edieval English Drama.

University of Pittsburgh Press, 1975. 99-121.

Pittsbur'gh:

Miyajima, Sumiko. The Theatre of

Pr in tin g Co. Ltd., 1977.

Potter, Robert A. The Engl i,:.h

Kegan Paul, 1975. 1-47.

Ma~.

Mor'~l

Avon, England: Cleuedon

i ty Plat.

London: Routledge and

Schell, Edgar.

"On the Imitation of Life"s Pilgrimage in The

Castle of Perseverance." t1edieval Engl ish Drama.

Ed. Jerome

Taylor ard Alan Nelson.

Chicago: University of Chicago Press,

1972. 27,'-291.

Taylor, Jerome.

"Critics, Mutations, and Historians of Medieval

Engl ish [Irama." t1edieval Engl ish Drama. Ed. Jerome Ta;/lor and

Alan Nelson. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1972.

1-27.