Chemistry Department Chemical Hygiene Plan and Safety Manual September 2014

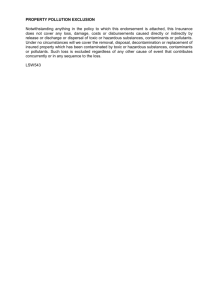

advertisement