Box B: Regional Economic Performance

advertisement

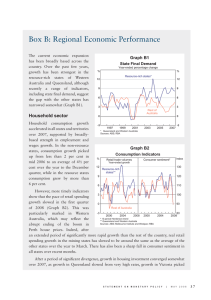

Box B: Regional Economic Performance Over the past few years, economic activity has been strongest in the resource-rich states of Western Australia and Queensland, while in other states it has eased noticeably (Graph B1). Two main factors have contributed to this disparity. First, resource-rich states have most directly benefited from the sharp increase in world commodity prices in recent years. Second, the earlier run-up in house prices resulted in Graph B1 reduced housing affordability in State Final Demand the larger states; in the case of New Year-ended percentage change South Wales, this has contributed % % to an outflow of migrants that has 10 10 Resource-rich states* slowed the pace of economic output 8 8 in that state. All the states have benefited from the recent commodity price increases through multiplier effects across the whole economy, dividend distributions from resource companies to domestic shareholders, and other channels.1 However, the stimulus to activity has been strongest in the resource-rich states of Western Australia and Queensland where mining accounts for a larger share of output. Activity in the more manufacturing-oriented states such as Victoria and South Australia has been more subdued, in part because the large increases in commodity prices have been associated with a period where the exchange rate has been above its post-float average. During the past year, the faster growth in the resource-rich states has owed largely to strength in business investment (Graph B2), reflecting strong growth in mining-related 6 6 4 4 2 2 Rest of Australia 0 0 -2 -2 -4 1997 1999 2001 2003 -4 2005 * Queensland and Western Australia Source: ABS Graph B2 Business Investment 2001 = 100 Index Index 200 200 Resource-rich states* 180 180 160 160 140 140 Rest of Australia 120 120 100 100 80 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 80 * Queensland and Western Australia Source: ABS 1 See ‘Commodity Prices and the Terms of Trade’, Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin, April 2005, pp 1–7 for a more detailed discussion of the channels through which an increase in the terms of trade stimulates activity. S T A T E M E N T O N M O N E T A R Y P O L I C Y | M A Y 2 0 0 6 31 Graph B3 House Prices and Migration New South Wales Ratio ’000 2.0 40 Relative house prices* (LHS) 1.8 30 l 1.6 20 1.4 10 Net population flow ** (RHS, from NSW to rest of Australia) 1.2 1993 1996 1999 2002 2005 0 * Ratio of Sydney house prices to other capital cities, APM composition-adjusted measure ** 2005 observation based on first three quarters of 2005 Sources: ABS; APM; RBA Graph B4 Dwelling Investment June 2000 = 100 Index Index Other states 110 110 100 100 90 90 WA 80 80 NSW 70 70 60 60 50 50 40 1997 1999 2001 Source: ABS 2003 2005 40 engineering construction. In addition, domestic demand in the resource-rich states has been boosted by buoyant consumption growth, which has been weaker in other states. Differing trends in house prices and in dwelling investment have also accentuated the recent divergences across states. During the house price boom, prices grew most in Sydney, with prices at one point almost 90 per cent higher than the average level in other capitals. This contributed to population outflows to regions where housing was relatively more affordable and economic activity was stronger (Graph B3). The resulting slowdown in population growth in New South Wales reduced growth in consumption and contributed to a fall in dwelling investment in that state. In contrast, dwelling investment has continued to expand in Western Australia and has been broadly stable in the rest of the country (Graph B4). However, the population outflow from New South Wales now appears to have slowed, possibly reflecting the fact that house price relativities between Sydney and the other capitals have moved back towards pre-boom levels. Consistent with these developments, Western Australia and Queensland have experienced strong growth in employment, while employment in the largest states has expanded more modestly. The sustained strength in employment growth in the resource-rich states has seen their unemployment rates fall substantially. However, in part reflecting the equilibrating role of migration between states, there has been broad similarity in movements in unemployment rates in all the states over the course of the current economic expansion. Finally, despite the differences in the economic circumstances faced by the states, the extent of the recent divergences in the growth performance of states is not unusually large. Much 32 R E S E R V E B A N K O F A U S T R A L I A larger divergences – as measured by dispersion in the growth rate of annual gross state product (GSP) – have occurred in earlier periods, as states entered and exited national recessions at different times, and during the terms of trade shocks of the 1970s (Graph B5).2 R Graph B5 Dispersion in Growth between States* % pts % pts 5 5 4 4 3 3 2 2 1 1 0 0 74/75 80/81 86/87 92/93 98/99 04/05 * Standard deviation of annual GSP growth, weighted by state shares of national output Sources: ABS; Harris and Harris (1992) 2 Data for the 1980s are from Harris CP and D Harris (1992), ‘Interstate differences in economic growth rates in Australia, 1953–54 to 1990–91’, Economic Analysis and Policy, 22(2), pp 129–148. S T A T E M E N T O N M O N E T A R Y P O L I C Y | M A Y 2 0 0 6 33