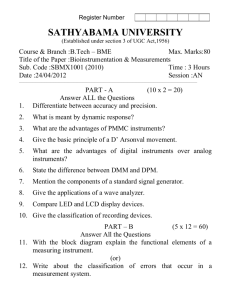

BALL STATE UNIVE1SITY ID 499 1965 J.

THE TEACHING OF STRING INSTRml;ENTS

IN THE UPPER ELEMENTARY GRADES

SHARON J. HA\\KINS

HONoa.S THESIS, ID 499

BALL STATE UNIVE1SITY

ADVISE1: DR .. KILLIM~ CASEY

MAY 28, 1965

I

-7L1 f-I

!qb

5

.I--(j~

TABLE OF OONTENTS

IN'rRODUCTION

•

•

• •

•

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Page

1

Ohapter

I. THE PLAOE OF INSTRUPENTAL MUSIC IN ELErrENTARY

SOHOOLS • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Values of Instrumental Program

Purposes of String Program

Problems of Beginning Instrumental Program

3

I I . DEVELOPHfu"qT OF ELf.MENTAaY INSTrtUMENTAL PRO-

GaMI • • • • • • ... • .. • • • • • • • • • • • 12

Enlistment

Screening

Instruments

III. ;SOHEDULING AND TEACHING OF OLASSES • • • .. . . . 25

Lesson Types

Olass Schedule

Class RDutine or Nethod

APPENDIX ., ..

BIBLIOGitA.PHY

·

..

•

.

• • • • •

.

..

.

• • •

• • •

•

• • •

" 'I< •

. .

• •

•

•

• •

•

• • •

•

•

• •

.

..

.

1

•

I.HTRODDCTImr

11hen in 1 S57 t.he Ruse,tans sent up Sputnik I, the

United States suddenly became overly consoious about the lag in ~jclen.ce a.nd. math in our aohools.. The arts were all but neglected in the rush to catch up in the ttspace race.

n

We have not yet caught up in dramatic ach:i.evements

In spaCE; , although there 1s some argument in favor of our technic£Ll advance 1n space probes.. But we have regained a saner balance of education in which the arts are taking their proper place. Ivluslc 1s one of the mos·c express! ve of these

arts

f havIng several media of expression~ The medium

~th. which schools are becomlng increasingly involved is that of instrumental music.. However "In thin the instrumental program string classes are occasionally neglectedo This may be due 'too several factors, one of them being a general lack of acquaintanoe with the posslb:l.l1tles a string program can offer

I:'

And this may include the non··realization that elementary set.ool 1s the place in whi(lh such a program should be begun ..

This paper w1ll, therefore~

try

to dascrlbe

many

•

2 aspects of a. strtng 1 instrument program that are possible in an eleml")ntary school.. It will be a general overview of the values of such a program, the means of developing a program, and met:~odB of conduct ing a string class.

------.,........

-....,....._._---------------------not havl;:! the usual ed form in a;n.y of the liri tings thlel

1Despite its use as an adjective, the word

!lri~ upon paper was based:" Therefore

~Finll instruments rather did lfhich than ~~R5ed instruments will be used throughout this paper.

3

I.. TH:~ PLAOE of INSTRUKENTAL MUSIC in ELEI-1ENTARY SCHOOLS

Values of Instrumental Prof~am

One of the first things to consider 1s the place of the ins.~~rumental program in an elementary school. Of what value il~ 1 t to thE~ child? .And what are the particular values that string lnstru.i11ents offer?

To consider the latter question first, one must consider the advantages whioh are related to the development of the appreciation of music in the United states which string lnstrumf~nta hold.: Morgan in HB,sic .ll\

,~er1can ~ducatiqn suggests that there is now a grea.ter acceptance of and an appreoiation for good music. And he believes that because of the ris.~ in ticket sales to musical events, in record sales, of musi(~ sales, etc., music is a. profitable business. Many of thesE~ musical events feature symphonies,. oratorios, operas, etc. These depend on the orchestra, nhich is composed of 10% strings .. 2 Therefore .. demand probably equals, if not exceeds, the supply of strlng players--whose training should begin rather early •

Dykema and Oundiff have suggested certain advantages

------------------------------------------------------------

2~usic

Book Number in 1~er1can

Tl~o7i;,a:

Education: Music Education Source

!laleT S:;-1E:j;g'Wl

(chicago;= .f4ENC tt

(955)

$' "

PP. 166-610 ' -

4 in the study of string instruments nhlch might be more evident to the ohtld., String instruments, they maintain, are somelfhat less fatiguing to play than are the \'J"ind instruments.

Therefore in an orchestra the parts for the wind instruments con'~ain many rests ",hi1e those for the strings have few, thus providing continuity and giving the string instrumellts generally more interesting parts~ The authors, too, go so far as to sugees1~ that because string instrl.lments can be pl.ayed by both b01:;lng and pizzicato, they are more versatile o

3

Morgan of.-Cers other reasons for preferring strings to other insi;ruments. For one thing, mU>J,h is written for string groups of all sizes and abil:i.ties. Secondly, strings blend

'l-1e11 ,.;i th a:n.y ensemble and are good accompaniment instruments.

Also violjLns are aVf~ilable in half and three-qua.rter sizes, which means a child of any 81 ze could play ~\n instrument which would f1 t his size.. A fourth advantage 1s that students ge~. good ear training through playing str1ng instruments

9 dUl!' to the open fingerboards on string instruments which have no set stops for notes as those on most wind instruments~ And finally there 1s a great opportunity for talented and industrious stud en t S t 0 aa.vance. 4

Morgan offers the following eight areas of the Child's life 'tihich will be enriched by participation in an instru-

-----------------_

... -

-------

3Peter vi.

Dykema and Hannah M. Oundiff t

School Music

Handbook: A Guide for Music Educators (Boston:

&

Company,)

1955), p~~5'~

'R"

-c.-a. lUrchard

4uorgan, 167 ..

5 mental Dlusic program: performance, musical, social, cultural, personaJ.ity~ physical, professional, and hobby.5 Into these eight areas all the values suggested in other 1'Trl"t1ngs neatly

Performance, the first area listed above, is considered by }1crgan to be the most important one. because learning to play thn instrumer.t is the 1..'1i t1al and ultima:te goal of the student.. This is the goal vlhich sustains the child's interest and rei>rards him when he learns to play the instrutnent o

6

The second area 1s the musical value that a string progrgJIl oan so effectively afford a child. As l-;as just mentioned, strings ma.ke U9 the bulk of the orchestra and are generally oO!lsldered to be the most important section in an orchestra.

o

Strings are also very imlJOrtant as instruments for chamber music

00

Because string players are brought into contact "li th music of a high caliber, this is an important type of music that is written fer strings. 7 And playing an instrument provideH an effective and enjoy-able

way

of teaching notation, rhythm t meter, etc., as 'tiell as prep<1.rlng for sight singing and preI)aring for the creative activity of composltiono

8

Every part has a noticeable importance, and to be able to play lv-ell requires a lot of VTork from a person. Therefore a person who can perform adequately uill not be lazy in this

5]biQ.4' 169-711

• _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ O_I -_

..

8Dykema and Oundiff,

275~ 7Ij?id .. , 170 ..

,

6 respeet

<)

And an Qut,standlng :performing abil1 ty comm8.nds a

~Gype of prestige that can override usual social barrters. 9

..t1Jl important area this type of program '~';ill affect is the cultural area" Even though a person will not become a professional, he gains a better understanding and an appreciation for good music throtl{r,h exposure to 1 t rlhen learning an instrument in schooL, Horgan goes as fa.r as to state that

"active participation on a strj.ng instrument is one of the best and most thoroup-)1 routes to a cultural understanding of good muslc,,"1Q What better llay could a chIld from a oulturally deprived area beoome involved actively in such music or one from a culturally advan.ced home find some measure of' enriohment for ;>That he already enjoys?

Morgan also ~ives the instrumental program a great deal of credit for affecting the childts complete personality:

The continuous association w'l th people in groups gt re:h.earsals# concerts, banquets, etc .. , gives the stude;~t an opportunity to develop many personali ty tra,l ts far removed from music.. His manner and taste in dress, evalU.atton o:E' frlendshiDs, and his ubil! ty to meet and converse with people villl be influenced o

11

Morgan also feels that

11 . . . . . . class lnstrv.ction and ensemble participat:Lon afford a real sense of feeling of accompllshment","12 And for a self-conscious child, playIng an instrument is often easier than singing, because the instrument is not as personal aEl the voice.. The objective here 1s not so much the

-------------_._._---------

9IliJ()rgan, 170.. 10l1llJl .. l1 1Jll.f!. .. , 170-71.. 12.;rbid

7 product1.on of sO'U...'ld

8.S it is the feeling acquired when playlng. 13

The physical develo~ment of a child is not neglected with an instrument. Through training, a person's ear will groll in ubili ty to distinguish pitch and quality. And his muscular system develops an agility and a sensitivity to

rhy-

thros

~

1l:-

The professional -values of a string program may seem negllgi ble at the elemen-cary level, but for the far-seeing child vilth professional goals in -the field of music are manY' job oppor~Guni at reasonable salaries. Such opportunities include, besides that of a professional orohestra member,

.

" .. television, radio, s~mmer opera. 8010 concert engagementa, an.d teo.ching. 1f15 The elemen'tie.ry Bradee a.re not too early to begin preparations for co.rears in these areas.

And for the child not inten.ding to become a professional the progt'am will lay the basis for his forming a hobby later on, such as one of collecting, studying, making, or repalrlng strillg lnstrumelltS

9

Or he can participate in small groups as by belng a member of the National Association of Amateur

Ohamber j'msic Players .. 16

~rhe instru1:1en.tal program, therefore, enrlches the child t s musical l~xperience ifhile he has the time to aavance and the flexi biLL ty to do so -; It invol vee the whole chlld

II rather than jus'~ his voice~ and 9rovic1es creative use of his leisure

-_.

16Ybld

time.. F:~nal1y the program is

8. transi tion bet1i~eell the primary rnyi.hm band and the junior a.nd senior higb orchestras, which ma~r serve as preparation for a musice.l profession.

Purposes of a String Program

~:he values of an elementary string class should by now seem ~vident, but thf.:: quality of such

11 class 'frill determine the exterlt to which these values are realized.

Elementary and Secon.dary Schools," suggests that to justify the existence of an elementary instrumental program in a school,.

-the program must mal\:6

• • • a significant difference in the pupil's conception tion, of music, hts uuders"tanding of it, and his competence with it~ The purposes of music educatherefore, are achieved only when a muslc program resul.ts in musical learnlng that would not talce place without i t.17

Leo!"..hard also believes that basic skills should be learned in the p:c-lmary grades and refined and enriched by challenging activities in the :In.termc-d.iate grades~

To insure a good program~ there should be certain begInning aims.. For one thlng~ every child should be al101'1ed to part1(~ipateo In this case the outstanding student and the child wi tll no talen'c lliJ.l l:'rop out

II the talented chIld to seel'C professlo:o.al help. Secondly the program should not attempt tary and

40.

1'70ho..rles

Leonhard~

liThe Place

Secol1dary Schools ~ ff

~ of Music in Our Elemen-

LII (April, 1963).,

9 to create soloists but rather should teach an entertaining hobby * And finally, to do this 't-wll: the child must ha.ve sou.nd teachln~ in fundamentals so that there is nothing to

"unlearn '.

U

Robert House in .l.~v.m.~p.ta.l !1B.sic, !9.r. 10day f.§.

SohEt>.f..§ has elaborated upon the objectives of 8.n instrumental program,

"'Thieh. lrould include the folloi'iing 1 terns:

Knowledge of:

I:

1) musical literature from all periods and idioms t

~2)

1:3) musical vocabulary and meanings,

': lj.} basic musical patterns and usaeea~ music a s development as an art,

(5) the principal forms and composers.

Understanding of:

I~ 1) pro blems in performing and learning to perform,

(2)

(3) the elements of good musical interpretation, the general

Skill in: methods by '~hich music i:8 constructed,

I: 1) producing a t'lch tone with acceptable intonation,

(2) playillg 'lfl th reasonable fac111 ty and accuracy,

(3) performing by ear~

(4) reading mu.sic of appropriate difficultY:1

(S) performing 'Yilth others, independently. proper relation to the ensemble, yet in

(6) hearing and follouing the main elements of musical comuosit1on.

Attitudes of: -

(1) musical broadmlndedness and the necessary discrimination of quality,

('2) respect for music as an art a..~d a profession,

(3) intention to impro"lle onets musicianship.

Appreciation of:

('1) skilled and tauteful performance)

(2) good music :tn any medium,

style,

attending ";orth1'lhile concel~tSq 18 or period.

Habits of:

( 1) froquent alld efficient individual practice,

(2) proper selection and care of instruments,

(3) participatine; i"lholeheartedly 1.n musical groups ~

(4) proper rehearsal attendance, deportment, and attention,

(5) selecting good recordings~ searchIng for more musioally satisfying radio and TV progra...'1ls, and

M_._..,..

_ _ _ ~......

10

Problems of Beginning Instrumental :Program

But. even with such 't'fell-defined object:! ves, beginning

an

instrumental program presents several problems that touch all aspects of the program. For one thing, music departments may receive little or no funds from their schools. This forces the music director to superv:l.se fund-raising act:lvi ties. For general equipment Dykema and Cundiff suggest that the school be responsible for purchasing such items as supplementary portable stands and a va~iety of instructional materials at ea~h level, providing rDom for storage of instruments, and making provisions for regular serYice and repa.ir of instruments. 19 The purchase of instruments might be accomplished by donation or by parents end, if necessary, by fund-raising.

The director should not have the responsibility of purchasing all the instruments, but he should advise the purchase. Perhaps discounts wi-lib. large orders 'l'lould be granted. 20

One of the first problems of a beginning program is to develop sufficient interest in the DDogram. The director needs the support of the school administration, principa.l, teachers, parents, community .. and the intelligence and support of -bhe childretl... This support can be generated by informing the people through articles and demonstratlons. 21 itllother in.I tial p:'oblem, 'tihlch 1'Till be dealt with

19DYke:1:a and Cundiff, 233 ..

20.IJll.<1.,

'~82-83.. 21~.,

281-82.

11 later. is screening appllcants for class membership. Directors must declide whe"ther to alIov; anyone to play or to employ rigid entrancE~ requirements to their classes.

The two problems causing the most controversy in a school are the time and place allotted for rehearsal. Becaus8 mustc programs of'ten are not included in the regular curricula, children affected have to go early or to stay after school.

Some authors feel that th~_s is an. unsc.tlsfactory arra.nBement~

Dykema and Cundiff, hO'Haver, suggest that students could divide th€lir rehearsal time ill'(;O half 1n school a.nd half out.

Th5.s ~'TOuld be necessary if their recommended amount of -time for reh€~arsal--fo'l'ty to sixty minutes-... was carried out. Dykema and Cune l .lff also recommend a separate classroom fC)r music but admit tl.lat any large area could be functional~22

A final major problem concerns the organization and instruct.ion of the progr8.~11.. The problem of instruction. according to various authors, is ~ ... hether to ~ra:tn a child for posl tlon inas. ba!l.d or orchestra or to .2.2J1cat~_ tbe musical thinking and feeling of a child. Various opinions conoerning this problem

1'7111 be dealt "t-ri th more fully

• _________ __ later" w_. _____

22lli.[ .. , 284.

12

II. DEVE10PgENT of ELEl;;ENTA lY INSTRur..'JENTAL PROGRAM

hnat

with all these problems, it is imperative for the success of a string class th~)t the enListment program be successful. Students Hill choose to plcy 1f they h~lve had a good general music o:,'ckground, if the strine:; group is successful, if the adminlstra'/jioll supports the program, and if they like the director. 23

Enlistment

House .feels that tlevery chIld should have advance knouledge about \-vhen and h01'T he may volunteer for beginning instruction~ For best results, this campaign should be ~hor ough and sustalned~ but noncoercive ..

1t24

There are several techniques that he mentions, and the director should employ three or four of them in enlisting members.

One techn1que 1s to have an announcement of the formation of beginning group:::> by the director follow'ing the performance of instrumental groups at a school assembly. This can include an introduction and a demonstration of various lnstrume1n ts 8.no, perhaps:r solos

(I

25

-----,,-

...

----------

.. ~-.---~----~-----.

23House, 63.

24Ibii,_, 63-6 /

.j.'.

25 Ib1d .. , 64.

13

P~other possibility 1s to have the dlrector visit classrDoms of potential st.ring members and talte along some of his aC.vD.nced players to demonstrate various instruments.

He can tben send home

E. letter to parents explaining the program alol:.g tli th a form for them to fill out and return. (See

APPENDL<) 26

A variation of the above theme is for the classroom teacher to make the announcement and to diatri but.e the letters and forme: to the children. Or before the director or teacher passes out the letters an(~ forms, the announcement might be given over the office Intercom. 27

~;ome other sur;gestions for enllstment include the use of b1'.lletin boards and/or posters; talks bY' the director to the P.T_1 .• , band parents' club, civic clubs, etc.; instrumental displays in the schools arranged in cooperation with local mue fc stc1res; announcements in school and local nmvspapers t on rad io anc. TV; and the inclusion in a letter to parents of the results of preliminary music tests. 28

Screening

One of the problems mentioned earlier was that of screening potential instrumental students. There are several methods by which this process can be done.. One method is to administe~ a music a.p·~:1tude test. The test must be one that

~

• • _ _ _ _ . . . _ - - . . . . . . . . . _ _ _ . .

14 is reliable, easy-to-interpret, and valId. Once the test is administered, the results should be interpreted to the parents.

S,ince apt! tude tests don't separate the good and bad rlsks, perhaps a better lndlcator of future achievement is a student's intelligence quotient. A student should first of all be capable of learning, [md good grades show both the Intelllgence and perseverance of the Child. Without an average

IQ or any indication of musical ability, a cllild should try to find aaother interest area. Carroll Copeland reports in the article "Beginnl.'rs for Instrumental Musicl! that studies

ShOi1 a corr'elation rJetl"reen music grades and grades in other clasBes~ especially math and readlng. 29

A third influencing factor 1s the social baokground of the ch:lld. The type of home environment indicates to some extent thf~ interest and future success of the child ..

.l~lld finally? a fourtl'~ indicator is the personal lnterview.. Throu~h this medlum the teacher c::m learn reasons for the child!1 s past successes and failures and of the child's

1-75.11 to succeed. b'1.th this information the teacher can decide if the chtld has a chance to succeed with an instrument.

The recommended ages for bAginlling players are generally the same in most references.. It is better for the child to have backGround in general vocal music before attempting an

----------,----------------_.-----._----------_.------

2S'Carroll Cope1811d,

Archie N .. Jones (Boston: l1l!.ill

Allyn and Bacon, in. Action ed.

Inc.~).

P!!. 216

... l7.

i5 instrument. Students in the fourth or fifth grade and older usunlly maet thir quallfication.. HO'i',ever Hubbard. believes a oh1ld CFln choose h10 instru.l1ent at the end of the second grade, and the J~IH;mese ·teacher Suzuki has demonstrated successfully that verso young children can play the violin ..

Khen decid1ne the Q.ua11ficatlons for students, i t is necessary to consider the physical characteristics which string playerE' l:a pn.rt:tcul~JT should have.. Ro~ert Hou.se has listed the .follo·~'i'ing qualifications for string players: (a) a good sense of pitch, (b) an aglle, fle:·dble hand large enough to reach all needed intervalR on all four strings, (c) a long enough rie;ht arm enabling the student to draw at least seveneighths of the bO'-!':3 len~~ and (d) the size of the 1nstrument to fIt the chlld. 30 Children may begin on half or threequarter size ins·truments

8...Tla £;1'11 tch to full

81 ze ones a.s they

IDz,ture. Those '\-1ho are a.l'rlnmrd on violin because of i·ts small size may switch to viola., cello, or bass ..

]'inally, in decld lug "iho should play an instrument,

1 t is advisable to consider the number of players with lThich j.t is convenient to 1-:orlc. If the director remembers that he exists for the orchestra snd not the reverse~ then he will not be overly concerned about the numbers. Ho;-;ever. he may still l'rork to promote enthusia.sm for certain instruments 1>1hich are in limited numbers in his orchestra.. Perhaps a band student

• p--. - - - - _ . _ - - - - - - - -

3

0House,

66.

16 mi8ht double on a. string inst.rument. in th too many players on one type of instrument, the director might get permission from the Hdmin1.strat1on to enlarge hie classes. In this case the competUiion is lceener) and treak students v-Il11 drop out more quickly.3 1

Once students have been screened, the next step is to decide lihen to bezin the progre,m.. If a fourth grade child or older has been approved as being physically and mentally capable and has had. a good general music background, he has passed screen:tne; requirements. 'No'tv he must demonstrate his t>;illing ... nes£: and ability to care for an instrument, practice it, and bring it to school.

Bef;1des the students' being ready, the director and school must be ready also. The director should ha'le adequate training, and he fl • • • must not have his eye entirely on developing the players needed for his performing groups, but rather upon the me~~s of creating the greatest number of successful players. "32 '.fhe school can cooperate by allowing the classes to be held during the school day. There should be no cost for thl~se lessons except for rental of school-o'\\rned lnstruments. And finally, as lras mentioned beiore, the school should furn~~sh a place for classes and funds for necessary materials •

....

'-

.,

61.

'\ t i

Instruments

NOH that the stu.dents :2o.ve heen screened and the school has f:urn1shed the director ~'ilth a place for classes and with the minimum mater:lals, the director oan begin doling out Instruments.. As he does so ~ he must ta}:e at least "~hree factors in.to consideration: the choice of the chl1d# the physical features

!)i' the chl:Ld, a..~d the means of purchasing the instrument.

The choice of the child should be the :lni-tlal factor in decid:I.l1g uhich 1nstrll.ment to play. 1Ji thout the desire to play an lnstrument f.rom the bee;innins, moti1re.tion and interest vTill be d~Lfficul

1u(l maintain. Often the chlld' s choice can be guided:, and he 1-1111 choose, for example,

9.Ji. instrument that his parents favor. 1·11 tchell recommentls le-tting the child ohoose hl(l Instrumel'l.t and allOl'Ting him to m-1:~t tch instrumrmts

1.f he so desires. 33 If the child ~,ra.nts to play an instrument but has nCI particular choiee, Morgan recommends the piano becausa 1 t [;1 ves lmmedlate s£'.tisfactlon.. He also says th~t more string players are needed, but that itlo1ins may bo tedious until the child masters intonation ,roblems. And there 1s no reason to exclude any instrument from the cholce of girls as is sometimes done.3 4

_____ ______ ._.

._._~

.. __

Be·~ter

33H•

!J}1 tchell, lIi'lhat Instrur1ent Should Your Child Play?

If

Homes and Gardens, XX'VII Ojovember, 1 S''S;') , 1350

34:',1organ,

13~3.

this next step is unnecessary.. HOitrever there may be a desire to play an instrument for l.,Thich the child 1s entirely unsul ted physically. There are certain i'eatures which are suggested as being beneficial in playing string instruments.

Bouse lists 8ener~1 qual1fications for playing all instruments: " • • • larger instruments for larger students,

. . . . agile instrUJ-nents f'or students of acile minds and hands,

[and]..

~

.. difflcul t instruments for students of pa.tience and extra talent."35

There are more specific recommendat1ons for string players. For one thing: a child should have long, slender i'illgers for re~.ching '.ntervo.ls p;j'Gclsely.. Because of a child ~ s small hand, violins and cellos are preferred as beginning instruments, s~"11 tching some stUdents to -violas and basses as the children grOitT. Cellists need strong fingers and a strong bowarm, a:1d basses :::equlre rather robust players.. All strings require players having exce!?tionally good ears •

. And. once a general fit of child and lnstruraeut has bean made, a more specific fit can be made 'tTl th half and threequarter s:lzes" The f'ollovTing list is one which can be followed generally in chOOSing instrt~ent size.

36

V~lolins for elementary schools may be purchased in one-eig..~th:l one-fourth, one-half ~ three-fourths, and full-size

InlJ,trumt::m1;s are reCOffiiJended. Violas are generally classi:f.'1ed

3

(:-

~jHouse, 67 ..

36

An addlticnal guide fitting the child's age level may be found in

:XOd?-l.f.§.

.§ch.ool~, p. 88. instrument size to the

House's book Instrumental

• q", - -

b;r length'3 in inchei3:

" .... 1 l ' d 16" Oellos come in one-

.fourth t' o:le .... h<:tlf, three-fourths, fl"!1d full sizes... One~fourth and one ... h::llf sizes are popular 111 the fourth and fifth grades.

Three-fourths is tho size recomrrended for General school use and full-31ze, if possible;. ]'or schools strlne; basses may come In one-four.th, one ... ho.lf, thrse-fou~('·t;hs, sevcn-eie;hths, and a f8'¥1 full slzes,,, Thouf!)1 one-f'o1.u'th and one-half sizes are often usDa. in elementaryr;rudes, ·they h8.ve a quaIl ty too much like

8. cello r s; t.herefore the three-fourths size is p1"9-

~'he above is a general rule: but there are also characteristi.cs lrhich morp. s!)eclfic:),lly alcl :In fltting students to instruments.

IH. th violins and violas larger sizes are approprls.tGs

:tf the ch:i.ld can ho:td them in playing l)Os:1. tion· 'so that the middle finger can r::;ach around the scroll and into the peg

'box. A c·311ist should be able to reach a major third in f'irst posl tion t,mc1 should be able to drm·;r the bOH full lengt~h in a strs.ight line... The cello should have a six to eieht inch end pin. It !3houlc1 res't at m:"~d chest lihen in playing posl tion.

Holding the bass perpendicular to the :floor (not using the end p:l.n), tho child should be stancl1:o.g strair;ht with his eyes on the

SIaIne level as the top of' the fingerboardo38

Once the inotrument,hs chosen and fits comf!ortably wi th the (~hild f s physique, it is then important the."1; there are enough instrtuner:'Gs to go aroun.d... Is it the respons! bili

• ..,-.

--~--_"_

. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _

3'i'Dykema and Cundiff,

575..

38House,

88.

20 of the school or of the child's .family to furnish the instrument? And uhnt are the steps to consider in purchasing an instrumeni;~

Ii. 1s generally agreed that the school should purchase most of the instruments, which 1"1111 subsequently be rented to the studel'J.ts. If it is possible, after students exhibIt a real interest, they shou1d purchase their OyID instruments.

Oocas1onally ld. th1n a community there will be people "Tho will donate instruments. And, if necessary, there can be a ftmd drive to raise the needed money.

When the parents or the school purchases the instruments, they should do so, acco:l:'ding to Dykema and Cundiff, directly from the dealer or by correspondence with him. The parents would do "i'llall to go through the school, as the director should know the rl3putable dealers .vho maintain established businesses.

Schools lih:lch place definl te orders payable at a specified time usually obtz.in the best terms. The dealers may sell for cash, 1nstl\~1JIlent, or for rental applied to purchase. Before the final transaction Dykema and Oundiff recommend aoquiring a written guarantee plus refenences that tI • • • might be necessary if the: purchase 't'1ere Inter to be examined by some other person."39 And houever the money is raised, it should go through the usual school financial officer. TolallOW for complete freedom to use as th~:: director sees f1 t, gift 1.nstruments must have accompanying forma~ transfers of olinershi~.

39Dykemo. and Oundiff, 573-74.

21 l~hether purchasing nei'i or second-hand instruments or receiving: gift instruments, the factor to consider along with cost is the condition

of

the instrument. The director should be relatively familiar with instrument brand names and price lists. A fairly reliable guide to quality of a ne1'1 instrument is its cost. Dykema and Cundiff have set up the following quality criteria for purchasing instruments:

A. Best quallty--for established or professional musicians

E..

C..

Good quality--for promising beginners

Fair ty--for exploratory lnstrument--replae;e with better grade for serious students

DeUncertain quality--for temporary use only40

Iwkema and Oundiff recommend new instruments rather than old unless the old ones are guaranteed to be sound by a repairman. Strings, especially, may need only a few repairs to keep them fit for further use. They do recommend, however, rebuilt instrmnents, which ",. • • are lcni"er in price and frequently are superior to new instruments at the same or even higher price. u41

One important thing to consider in buying a. string instrument is the body o~ the instrument: does it h:::1.ve any cracles or openings or n loose linine?

Do

the pegs fit, and are the string holes in the pegs well spaced? Is the fingerboard smooth and nl~it l'rarped or rutted? Is the head nut nei thar too high nor too loW'? Does the bridge need tri.:nming, and does the sound post f1 t? The condl tion of the bOl';

1s important, too.

22

Does the frog mechanism work smoothly, not being 'Worn or brolten" Is the bow 1'Tell-bal.anced and not lrarped, and does i t need rehuiring?

Once an instrument 1s acquired, i t can be kept in good oondi tion with proper care ~ How"ever ~ from time to time the

need

for

minor repairs

will arise, which the director should be able to care for. He should u q • • be able to re9lace strings, to repair open edges, to reset a sound post properly, and to cut dOi';'U a high bridge to the correct height .. "42 Other

more

serious repairs which are not the responsibility of the manu.fac turer or dealer, 1j"l11ould be talten care of by i tlnerant

repairman

oonnected with laree firms.

The care a student gives his instrument should include handling it carefully and keeping it from rapid temperature ohanges.. The bOlT must be loosened "t-ihen not being used to maintain ltlS shape and elasticity" Rosin should be cleaned off the instrument, and the instrument should be stored in a s·turdy case" If' possible there should be

Do

"tvaterproo£ case cover for inolemellt "leather.

House has considered -the need for school-ot-med Instrumenta and believes the follouing list to oover the general need: harp violin viola cello bass

1 e--i"2

6--10

4-- 8

BeeD,use violins are suoh popular instruments, the students may purchase their oim, and the school may not have to purchase any.43 ouse, c>-

90

•

23

House goes a bit further and says that the schoolmay not hnve to purchase

60 many instruments if students double OlL an instrument. This is praotioal only 1f there are practice rooms and lockers in which instruments and music may

be

stored. Such

an arrangement

should

be

restricted to only one year in order that new' olasses might use "these Instruments e

44

In

considering

the equipment that should

aocompany

the instrument, the follm,rlng is a 11.s·1] of recommended i tams. Violins will be considered first. The strings of a violin should be a steE:l E with e. screyi' tuning-device on the tailpiece. gut AI) aluminum .. ·wound gut D, and silver-'1ound gut G. l'!etal bO't'V'G are acceptable for beginners because they ""Ton! t t·m.rp and are in a medium price range: but i'TOoden bm-Ts are better for advanced players. Gener~l equipment needed with a viola include a bOW, a chin rest, and a l'looden case. Violas and cellos should have gut A and D and silver or copper G and 0 strings. Equipment needed 1"li th a cello includes a bow, a strong clo"th bag, rosin, mutes, a1],d a metal end pin. In an area of great climatic change, l'l'here cellos often crack or break open, plj'110od cello. may be satlsfacto17 instruments. Basses often

crack

open, too, because of rough treatment and. ueather changes. For these reasons the neiver'

plyt'TOod

types are some't'1hat sturdier. Bass strings should be gut G Qnd D

and

copper A and

E.45

Some people prefer different types of strings than

.....

- - . . . . "

45Dy1cema end Cundiff, 575.

those mentioned abcve; hOi'iever all-metal strinGs should be used spB.ringly as they produce a harsh tone. The most important thing is that the strings be of good quality and are in good concl.i tlon. 46

~he school should provide not only some of the instruments but should also provide other materials. Space for rehearsal is one of the most important. Storage space for instruments and uniforms, if available, is another necessity.

The sl~hool should also furnish some atands, tuning bars, and additional strings, bridges, and such parts as are necessary for the common minor repairs.

Finally the school should provide funds for an adequate supply of music for all levels. There should be some for

the

most likel1 ensemble and group arrangements ~ornmon to an elementary at:ril:lg and orchestral pattern.. And this material file should be constantly expanding.

Orchestral:; and Bands (Minneapolis: pany,

460harles Boe.rdman Righter, Success in Teaching SchOOl

194!3')-;-I>. 93:--

Paul

A.

schmitt

1-1usic Com-

2 -..,

III. SCHEDULING and TEACHING of CLASSES

Lesson TYlJGS

E"ren before a group of children has sho-w-n interest in playing illstrumen+ts:, it is neoessa,ry to decide what type of a program If.lll i1 t best into the school 81 tua'liion~ There are three basic types of progl"ams i'rhich ~,;an be adapted ,to a school: prlvnte tutoring~ homogeneous olasses, or heterogeneous classes.

The private tutorial method 1s one that is limitedly recomm,endE~d. And even ~;rhen i t is praotical to use this technique, it should be used with discretion.. Private instruc"(;ion

1s not advised for beginners, because it . requires much motivation, praotice drill, and high cost. lila!" second or third year stude,nts there is some merl t as 1'rell as for th"se 11ho are beginning a second instrument. Advanced students can profit i'rom priva.te instruction in refining techniques and preparing for solo ,\,i'ork, but even then authors hold that private lessons should be only for 6u!)'91ementary 'N'ork

0

If priVate lessons are given by a licensed teacher,

Alfred \c/o Bleckschmid"'~ believes they might be given during school hours", He states, honover, that if the teacher h~s no lieGnal? "Ghat it is often illegal to teach dur:1l1.g school time

Q

If the lessons may be given during schOOl hours, the prlnctpal

26 and classroom teacher must be consulted. J1.n.d if the tutor is not a member of the school staff~ he may charge a fee for his les sons. 4'7

Salom-e Berger,. ho'ti8ver, feels that the disadvantages of prlvat'9 lessons :car Quti";relgh the advantages o

She feels that (~oncentrated e.ttentioll on a c1111.d ·t;ellds to overemphasize the child's abilities and may make the child more egocentric than :l.s n,:>rmal. The child may realize his actual abi11 ty only after a public failure. Berger definitely states that

H.

• 9 in the! ma.~ ori ty of cases' the ·tutorial method has been fdund laoking.

".!j.8

~le group method of teaching is more widely recommendedo

Nany a.uth"ri ties recommend 'beginning in an ensemble a1 tuation

1'11 th strings separate from band in.struments. Some of the valuee that .j~hey attach to group l'l'Ork are social, technical, and economic builders.

Ohildren learn in the social s1 tuai.ion of a group because the~r enjoy shr.r:tng similar experiences. "They like learning from one DI.other ~ correcting one another, helping one anothE!r.. -They feel less shy and inhi b1.ted towards the teacher i-Ilten they confront him in a bodyo "49 .And wi thin thi s

-

~----

-------- -

---edo

67 ..

,>~.

"i'

I Alfred Vi .. Blecli:schmldt, Nusic

Educ~~tion in Action,

ArchiE' Ncr Jones (Bos·ton: Allyn-and PBacon:Inc:-; Ts:~orPPo 66-

4BSa l

InternatlcnaJ. ome Berger,

41s4Z;:--- ___

, _ , 1 tlTeaching Instrumental Playing in Groups

~~.~-

Education Journal (November. 1960

- - - - - tt t

,

, , )

27 enjoyment of group there is also chance for recognition through personal expresslono

Ohildren profit technically in group learning, too.

Most problems of one beginner are common to some or all beginners, and a child 1s not so easily discouraged when he finds others with the s~ne problems he has. The child 1s also motlvated to excel because better players will set standards he wants to follow., .And as the pupil struggles to keep up, he inadvertently beco:nes a better sight reader. This interaction wi th~Ln the group ,viII lead the better players to help weaker ones, improving their own tE~achlng skills. Because a child hears a 'work performed in a number of ways in a group, he will learn to evaluate these ways and will not rely on a teacher too much for criticismb These students develop a selfoonfidence in their playing. And as Berger adds, "Pupils who are trained to listen cri tioally \,Til1 in addition make intelligent concert listeners.

u50

'fhere are other advantages to group playing, too. It is economical both in the tlme i t saves the director and 1n the cost o£ private lessons the parents save a

Even with the purchase of an instrument. school fees are much lo·wer. Group work also oonditions a child to playing in a group, whioh tends to be cr:Ltical of oyer-all performance" This helps him not to have ntage fright before other groups. A ch1ld ,..,ho might

become a profess ior:~8.1 musician. has the opportunity to i-Tor1e i'lJ.t.h a group accompaniment." il..nd since all children who want to should have the OP1)Ortuni ty to play an instrumeJlt, group tt~ach1.ng mere democl'atically ena.bles them to d(. so.

~~he orge.n.l,;ation of a group may follow' one of three pattern:3: ldentic8.1 inst:r'uro.en ts, related instruments, or allY comhlnatlol1.. This usuo.lly depends

011

"the size of the

,::ChOO'

1

ID· us.-le '''ro ("'r nrn And t.he classes may be arranged :tn abill ty group~1 \·iltt.ln thiG framework o

~~he homogeneous instrumental. groupine is simila.r to expanded private le6sons~ but the advantage is in reduoed time.

The clase: call use one method book a.nd have the chance to explore ensemble 1'Torks" The probJ.ems of the group arise from the dlfi'iculty of schedullng--that is, drawing only a few children out of class at a tlme4

51

I'amily groups of' instruments B.re best sui ted to medium sized schools.. Thts method Harks because problems 11"ithin the gl'OUp are closely related ~ and the student can understand his problems better by comparihg tbem vllth those of other family instrumen.ts., Eore materlal is available "'Thieh 1s of tan more interesting than that for one type of instrument;, beoause the instruments assurne their characterlstic roles in family groupso

S'wi tching or doubling may be easIer ~ and scheduling in blocks is faCilitated.. The director 1 s main problem is to know all

5

1

House, 71"

29

-the l11strmnents and not to neelect the problems of any.52

Heterogeneous c1asses~ lf varied enough in composition, produce a small orohestra. In this case, scheduling may be arranged to a1 tern8. te 1..;1 th such olasses as physical. educe.tion or art, or it may meet during recess, study hall, or after school.. Progress 1>rl th such a variety of instru..ment.s will be

SI01'ler, but good hab! ts of instrument care and technique may be taueht to all.

53 Some authors recommend at leae;t a year's worle "ifi th the homo gene ous or

"'i"li th the family group before begin.ning in an orchestral s:ltuatlon.

Class Schedule

A problem that occurs almost simultaneously with that of class type is the scheduling of instrumental classes. There are several variables l"hlch may affect a schedule.. Dorothy

Bondurant in her article "Scheduling Instruments Classes n mentions the following seven:

1 .. be.ckground, experience, and preference of the director,

~'. the number of days per can be at school,

,·reek that a director

; •• the time he -rTould lose going between schools" li,. location and size of the rehearsal

room,

~i. the effect a involved, schedule l-Tould have on

6. the number of students,

7' .. the time available.54 each class

~:lss Bondurant also describes in this article the

1::4..,.

-' '..uorothy Bondurant, r·1usic Education in Action, ad ..

Archie N. Jones (Boston: AllYn aii'dBa'C'Ori;In'C7. 19t)O " 63.

30 three common types of scheduling patterns that directors utilize: the set sohedule, rotating schedule, and departmental schedule. vd .. th a set schedule a def'in!t.te t~.me is 8Bsigned for each class during the year. The student 1s released at a time which Is convenient to the classroom teacher.

The I'o"'catlng schedule involves advancing the student one half hour each lesson so he does not mise the same class two times in successiono

The third system 1s the departmental schedule, in which the school 1s set up in periods for each class. This includes periods for music and/or arto In this situation th~ child would miss no classes.55 A possible difficulty with this system is that a whole class may not elect to take instrumental lessons, leaving any number of children in the class while the rest v'l6re in their int;,\trumental classes ..

If none of these systems is completely satisfactory, lessons may be given partially or completely outside of school time. Dykema and Cundiff recommend this sort of arrangement

~\f the ro·tating schedule Is not practical to a SChool o

56

The recommended number of times the class meets per week and the amount of time per lesson varies from author to author. All recommE-md holding class at least once a l-jeek, preferabl:r more. Dykema and Cundiff suggest two group rehear-

63-64. 56Dykema and Cundiff', 284.

88.18 por(.;e(~J:;: of foC'ty to sixty minutes eaoh, half in and half ont of school t5_me, plus tt,Q more rehearsals of small groups

In wh:;.chnore

~_J1dlv~Ldu2.1iz8d attention can be glvcll,,57

In any

CaE;€ > the princ1pal should be consul"ced in a.ll

Gchec1:ullng of classes.

01ass Routine or ~1e1;hod

TJ1€ fiu8.1 item to be cOIlHidered in this paper is the matertalpresented in the class and thG m~mner in which j. t i

8 presented.. Speci.fic techniques for the toaching of each :lnstrument are left to mo:~e technical and professional works, such as teachi::1g manuals accompanJ~lng the child' s instrumental instruction books.58

T~:lC me.TIner In "\'ih1ch the class 1s conducted will be discussed first. F-lfLl'l.Y of the referenoes 1·rhich serve as bases for this :[)aper feel that a set routine is "(jhe most efficient

means

of organizine; a class so that the director may be oonearned only 'i'i"l-Gh tho actual mattel"' of teaching., One means suggested -'Go aocomp:.lsh thiD is to organize the group as a club. Tho of'ficers would then :relieve the dlrector of several detail.s 0:: the clasfJ.

59 Another :i.n the class routine suggested by Hubbard.. Ftrst

H chIld is 8.ss~lgned o. chair to be his :for each leasouil At the beghll"1:'l.ng of each class period he takes his seat wIth his i!'}.st:r'umen-'c, at-tends to ini tio.l dl.ri:;ies of r.::~p

Jj

--

5e A good li8t of these materials is found in Robert

'o()ol'" 'rr"s'!'r""'Gil"-'''l t..

~I':r·,~C'l

..... ,=',.;: ...•

... ~~ t"chools pp c'

98 99

..,.. •

32

adjusting the should~r pad ~ roslnlng the bOI';, etc., and waits for the teacher to tune hiB instrument if he is not able yet to do it" At the end of the class he must oarefully put his instrument away and leave the music room in good order.

60

Once the cDild is accustomed to a routine~ the director can concern himself more 'tilth teaching. He 1'1111 f011011 a general pattern In teaching beginn1n13 strings" His first lessons teach the child about 11is instrument~ the names of the parts, hm·r to hold it, and hOi-I to produce a tone.. The director, as

1-laS st.ated before, w'ill tune the instruments at firEii; and 1"Ii11 teach the child to tune his instrument as soon as he adequately can. Next the director will teach simple m~locl1 es which the child can learn by rote (' As the director gives in13tructlons;) he i'Till be careful to use the simpleE1t lant,"'uage possible, at least f1 tting his vocabulary to the past musical (~xperience of the child.. He should adapt a halfindividual, half-group method of teaching by giving a general instruction to the class, then moving from child to child as they pIa;r t i l l all have mastered it"" The. piano should be used limitedly, and the director should let the children play throu.gh the music rather than alrlays playing for them. The director should close the class with a familiar songo

60George E ... Hub'bard, !11!si9.,

~lJlng,

.!,!l

~ grad~§.

(Neii York; lI .... llerican Book Company, 1934), p ..

1~7

..

33

Hubbard suggests a more rigorous routine, v;hlch -vTould be suit~ble for rul advanced elementary class. The initial actlon of a class period ls, of course, "I;uulng. Many of the ch:1.ldre:o. should b'3 able, by tbe beglnning of the second year ~ to tune their own instruments. Next there should be a review of the 'iV'ork presented in previous lessons<>, This ivould include

"technic al problems, problems "t,yl th the musio, and problems of notatio:1l and rhy'thrn" Then the director l'7ould lead the class in playing something of their own choosing~ After this he would l:i1troduce some new w-ork

J presenting the nel'1 technical problems, ne'w rhy'thmic, notational, or musical problems, and new problems of interpretation. Finallythe direotor would hold a recital perlod.

61

There are other methods of teaching advocated by some.

One of these is the method of teaching piano by films that is used in Paris. W:lth this method stUdents watch films of wellknown pIanists playing correctly. Students are able to see the correct method immediately without having to discover it for themselves. 62 This could be adapted, perhaps, for other instruments.

-

Another method is that mentioned earlier which is em-

......... .

61Ibl~c, 185-86~

62Louta structl(>n: The

]ducat~2.!b

A

Nouneberg, tlA Ne't-J' r':ethod of Instrumental In-

F5.lm as a Heans of Nusic Education," I-lusic

J.eport to the International Conference on and Plac:e of Musle in the Education of Youth and the

Adul ts , in

RDle

Brussels,

June 29 to July 9:,1953 (S'wltzerland: UNESCO, 1955)p p .. 2520

.~,

.

1

",(:.,.'

'

. ployed by Professor Shinlchi Suzukj. in teaching young childron to pl~y the violin. The professor teaches the mothers of these chlldreL to play the violin. The mothers then play simple

Bach gavottes and other classics before their children till each chi 1d l"rants to learn to play. The mot.i vat:lon has apparent-

1y been very successful. ~Che children learn ·~o play by listening to records and by cons~Gant repeti tlon. The children seem to gain sen.sitivity as well as technical abllity. Ahout five per cent of them decide to become professlonal ...

63

Suoh methods as these haye been tried in limited areas, and opinion of their l'iorth,l perhaps, should be reserved till more work with them has been successfully attempted. Till then the traditional approach 1'1'i11 probably be the most rarTarding ..

A fine example of uhat an instrumental program can offer to all ages of school children is exhibited at the Burris

Laboj'atory School, vlhich is associated i-Tli.;h

Ball state University, NUtlcie, Indiana. Elementary children are introduced to fine music from the begirlUing

1'11 th the emphasis on their enjoying playing their instruments. The~r director,

Dr.

John Cooley, recently conducted a string concert which demonstrated the full range of participating students; elementary through high schoolo

The elementary an~ junior sections of this April 30, 1965, concert ehoN's the progression of the str.ing program from fourth

- -.... -•• _ _ _ _ . . . . . . _ ..

• • .... _ _ _ _

35 to eigl1"~h grades.

Fourth Grade Strings

"Holy, Holy, Holy"

Glgue from "Sonata in

(4th grade violin solo)

"Black Havrlt vIal t zit

F"

Elementary String Orchestra

"Ting-A-Ling lt

(5th gra~e viola solo)

HDuet i11 G Maj ort!

(5th

grade cello duet)

Junior String Orchestra tlAllegro Spiritosoll

(4-5)

Isaac

Traditi.onal

Hohmann

Senallle

(6th grade violin solo)

Traditional

Handel tfBourree" Squires

(7th grade cello solo)

"1,1ummers tI

(8th

grade string bass solo)

Allegro from t'Eine Kleine Nachtmusik

(Junlor str1ng orchestra, tt

6 b.

Isaac l\1ozart

This paper has attempted to show the values of an lnstrumnntal program, part:tcularly of a string program to a child, the need for it in the schools, how such a program ol~nld be org8,nl zed

It and '-That its e::nphasi s should be.

It is 't~l'i tten froIT. a layman

IS vieivpolnt and 1s direoted to those who are in t€rested in \·jha t has been done and what might bEl dOlle in this area o

---------------------------------------------------------------

64

April 30,

11 The Burris Strings," dlr. Dr. John Cooley (Burris

Laboratory School, Muncie~ Indiana: Ball State University,

1965),

p. 20

APPENDIX

The folloiving letter appes.rs tn ;\.obert House

S s book

.!astrume:~ ~J...9. i l l 1'.£sL~y"'§. ~29..~, p .. 64. It offers a very thorough and :tnviting description of a very effective elementary instrumental program. The form~ which 1s to be returned by parents, is also from this book, pp. 64-65 ..

April 15

Dear Parent:

.t·1any of your child l s classmates 1'lil1 be electing beglnn:mg instrumental instruc'Gi(~n this fall or summer. lie hope your chtld '1'1111 also participate.. Groups will be formed that will meet 110nday through Friday this June 2-July 11. Other classes, meeting twice a week during school hours, will start in Septe:nber. There is no oharge for this instruction.

A.s soon as each pupil 1s ready I."? 1 there is an opening. tfl he will be adml1;ted to one of the performine; organizations, provided give all learn

It is dlfflcult to tell whether a child 1s musically talented.. A general estimate is provlded by

Volunteers, but a more reliable guide is the child's general success in to play is the most important faotor .. the test we school. HO~''iever, his adtual desire to ticular

It is even more difficult to determine the instrument

1'7hlch 1'T111 be most sultable for your child

:Lnstrument is desl red ~ ~"1e o

Unless a parwould like to advise you on the c11oice, using general. physique and future openings in our grou:?s as a basis. In some instances it becomes apparent after a time that a change "to another instrument :ts advisa.ble.

. For ti11s reason it is not rii sa for you to purchase an ins"C!'umeu'l; too soon.. The school owns several -::~"'hich may be

rented for one year at a moderate charge. The local music store v.*~.ll also arrange to rent you an instrument [sic) and

::,;n::r pa.ytlents may be applied to a lc.ter purchase.

We believe that learning to playa musical instrument can child's be one of the most cherished experiences in your l1.fe« Th.e 1m

01"11 cd ge and skill he acqui rSl3

Kill be useful

1:;0 hlm "V':hether i t becomes avocation,

Em avocation, or a memory to

1'li11 you con.sider the matter carefully and return the folJ.ow'lng questionnai:ce?

Sincerely,

~r '* '* * *

( Please mail or bring to the school music office by r~ay 1 st. )

Our

child lfOUler. li.ke to participate in the groups starting

- thi. s summer next fall

InstrumElut choice,

We would like to discuss the possibilities with you. Ou-r---c~h~i~id~d has a strong desire to learn the

$

In procuring the 1,nstrument, i'Ie prefer

________ to rent a school instrument, if available

_______ to arrange for an instrument independently age phone

HI B.1I OG~tAPHY

Berger, Go.lom'€!" f1T;9achlng Inetru.mellt2.l rlaying in GI'OUp~~. tl

I:aternatioL'ln.l .soc).et~r for iJlu.sic Education Journal ..

"~'4r:1f4:- ,",,'.-'~--'

Dykema.,

IIFiQ'dJi':"7, ""e g

J.Lr.' " u (March 23, 1964), 72.

Gehrkens:o Karl 1111Gon. Hu.sic in the Grade Schools.. Boston:

0 .. 01> Birc~la.X'd &~'-dO:':~ r?3~ ----~.

Hooper~ Great Britain:

Hubbard, George EOl

Ifl;;w York:

Jones~ JI.1.'ohi e N ~ ( ecL~ ) ~

Allyn a11d Bacon,

Boston:

Leonh£.rd., Charles. "The Place of Music in Our Elementary a:ud Second.ary Schools ..

If

NEA Journal, LII (1\.pr11,.

4.()-42

I)

~- ~':;M.""~£Q""'_ .

1963) ..

.". rili tchell ~ H", t!

(-that Ins-'..;rume'ut Should Your Ch5.1d PJ.ay? t1 lli~ .. ~.£. ~d,"~§.., X:':XVII {l~ovember, 1959), 135~

-

Er.8.2~e]. II ~ (eel ~ ) if

EdllC8.tio:n

[;;Oi.l:CCe

T9~r~r.;~"'~~~ ~~~~~~~r

N01.mt) berg: Lout;a" Ill\. J;;e\.;' Uethod of Instrttm6ntal Instruct1.on.:

The F:tlm as a

!Jl€a!l!3 of i.:iusic Education, tf

1·11.18:10 :i.n

.r ._.,,:~,.... '~"'<M

.!.i:ducatiOl1.o .f\. rep!):~ t to

~on""theRole

'the International Conference and Place of Yius:lc in 'the Education of

Youth and Adults, J'3ruaGels,:,

JUl18

2S' to July 9~ 1955",