Housing Prices and Entrepreneurship: Evidence for the Housing Collateral Channel in Australia

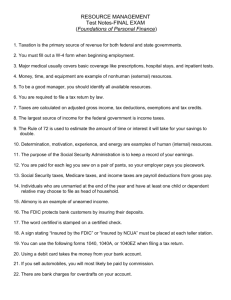

advertisement