Modeling and Assessing Secure

Voice over IP Performance

by

Cory L. Zue

Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degrees of

Bachelor of Science in Computer Science and Engineering

and Masters of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

at the Massacusetts Institute of Technology

May 24, 2005

IDE

-C*

IF

Copyright 2005 Cory L. Zue. All rights reserve

MASSACHUSETTS INSTiTUTE

TECHNOLOGY

JUL 18 2005

LIBRARIES

The author hereby grants to M.I.T. permission to reproduce and

distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis

and to grant others the right to do so.

Author

Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

May 24, 2005

Certified by

CrfebRobert K. Cunningham

Associate Leader - Information Systems Technology Group (Lincoln Lab)

Thesis Supervisor

Acceptedb

A e bArthur C. Smith

Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students

BARKER

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

2

Modeling and Assessing Secure

Voice over IP Performance

by

Cory L. Zue

Submitted to the

Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

May 25, 2005

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of

Bachelor of Science in Computer Science and Engineering

and Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

Abstract

Voice over Internet Protocol (VoIP) systems enable efficient communications over

data networks, but security of VoIP and the impact of that security on communications quality has not been quantitatively modeled. A conversational model is adapted

for VoIP and a computational model of communication quality - the Z-Model - is developed. VoIP conversations are simulated for networks with a range of performance

characteristics including differing bandwidth, latency and bit error rates to evaluate

the impact of security on communication quality. Results show that improving confidentiality via encryption of conversation data packets does not introduce significant

delays, but does increase bandwidth. In certain restricted-bandwidth environments

this results in dramatic reductions of perceived conversation quality.

Thesis Supervisor: Robert K. Cunningham

Title: Associate Leader, Information Systems Technology Group

This work is sponsored by the United States Air Force under Air Force Contract FA8721-05-C-0002.

Opinions, interpretations, conclusions and recommendations are those of the author and are not

necessarily endorsed by the United States Government.

3

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

4

Acknowledgements

There are several people whose work and input went into this thesis. First I'd like to

thank my parents, for putting me through college and supporting me both financially

and emotionally through some stressful times. From Lincoln Laboratory, I'd like to

thank Lenny Veytser for the use of his tool for analyzing network traffic, and Mark

Yeager for porting my VoIP traffic generating code into a scriptable format. I'd also

like to thank Aaron Beveridge for putting up with my constant requests for help in

various administrative tasks. Mostly, though, I'd like to thank my advisors: Rob

Cunningham, my official thesis advisor, and Cindy McLain, who, although her name

is not on the cover, put as much work into this thesis as any advisor could. Rob

was terrific in keeping me on task and seeing the big picture, while Cindy analyzed

my work with an incredible attention to detail, making sure facts were checked and

grammar rules were not broken. I feel very fortunate to have had not one, but two

excellent advisors willing to work extra hours and late nights to ensure that this thesis

got finished. To both of you I owe an incredible debt of gratitude, and probably a

few hours of sleep.

5

THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

6

Contents

1

Introduction

14

2

Background

16

2.1

Before VoIP: Telephones and the Public Switched Telephone Network

16

2.2

The Internet . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

17

3

Voice Over IP

19

3.1

System Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

3.2

History and Growth

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

20

3.3

M otivation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

3.4

VoIP Deployment Challenges

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

3.4.1

Infrastructure Requirements . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

3.4.2

Factors Affecting Conversation Quality . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

3.4.3

Security . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

24

4 VoIP Implementation Details

4.1

4.2

5

25

Call Setup Protocols . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

25

4.1.1

H .323

25

4.1.2

Session Initiation Protocol (SIP)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

27

4.1.3

SIP versus H.323: A Comparison

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

28

4.1.4

Others . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

30

Transport Protocols . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

30

4.2.1

Internet Protocol (IP)

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

30

4.2.2

User Datagram Protocol (UDP) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

31

4.2.3

Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

31

4.2.4

Real-Time Protocol (RTP) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

32

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

VoIP and Security

34

5.1

34

Internet Security Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

7

5.2

6

5.1.1

Definition of Security . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

34

5.1.2

Security Details . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

35

5.1.3

Security Implementation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

38

Security Applied to VoIP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

41

5.2.1

Confidentiality

41

5.2.2

Integrity and Non-Repudiation

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42

5.2.3

Availability . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42

5.2.4

Security and Quality of Service

43

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Measuring Conversation Quality

44

6.1

Mean Opinion Score (MOS) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

44

6.2

Perceptual Evaluation of Speech Quality (PESQ)

. . . . . . . . . . .

45

6.3

E-M odel . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

46

7 VoIP Conversation Modeling

48

7.1

M otivation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

48

7.2

Brady's Model for Two-Way Speech . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

49

7.2.1

One-Port versus Many-Port Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

49

7.2.2

The One-Port, Two-State Model

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

50

7.2.3

The One-Port, Four-State Model

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

50

7.2.4

The One-Port, Six-State Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

51

7.2.5

Model Parameters and Interpretation . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

51

7.2.6

Model Limitations

54

7.3

Applying Brady's Model to VoIP

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

54

Voice Activity Detection (VAD) . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

55

Revising Brady's Parameters . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

56

7.4.1

Correlating Brady's Data with the Switchboard Corpus . . . .

56

7.4.2

Comparing the Switchboard Corpus to VoIP . . . . . . . . . .

58

Developing User Models . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

60

7.3.1

7.4

7.5

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

8

7.6

8

7.5.1

The Average Speaker Pair . . . . . . . . .

62

7.5.2

The Authority Relationship

. . . . . . . .

62

7.5.3

An Alternating Protocol . . . . . . . . . .

65

Sum m ary

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

68

Adapting the E-Model to Secure VoIP Systems: The Z-Model

69

8.1

Using the E-Model for VoIP Communication . . .

69

8.1.1

Jitter . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

69

8.1.2

Echo . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

70

8.1.3

Error Rates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

71

Going from E-Model to Z-Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

72

8.2.1

72

8.2

8.3

Modeling the Effects of Security . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Incorporating Conversational Improvements

. . . . . . . . . . .

9 Resources

74

77

9.1

Traffic Generator . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

77

9.2

Link Emulator . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

77

9.3

Encryption Devices . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

78

9.4

Test Network

78

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

10 Methodology

80

10.1 Understanding the Performance of Secure VoIP

. . . . . . . . . . . .

10.1.1 Experiment 1: Performance Under Optimum Conditions

80

. . .

80

10.1.2 Experiment 2: Performance of Openswan with Increased Traffic

82

10.1.3 Experiment 3: Performance over Low-Bandwidth Links . . . .

84

10.1.4 Experiment 4: Performance over Links with High Loss and Error R ates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

86

10.2 Adding Security to the Z-Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

88

10.3 Evaluating the Performance of the Z-Model

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

91

10.3.1 Evaluating the Disagreement Factor as a Replacement for Absolute D elay . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

91

9

10.3.2 The Loss Due to Errors

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

93

10.3.3 Using the Z-Model to Estimate and Measure Overall Conversation Q uality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

94

11 Future Work

11.1 Conversation Modeling

98

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

98

11.2 Security . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

98

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

99

11.4 Voice Quality . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

99

11.3 Network Characteristics

12 Conclusion

100

10

List of Figures

1

A Typical VoIP Setup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

2

An H.323 Call Setup . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

26

3

A SIP Call Setup and Takedown

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

29

4

Evaluating VoIP with the PESQ Model

. . . . . . . . . . . .

45

5

R-Values and MOS for Varying Conversation Quality[58] . . .

47

6

A Two-State Conversation Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

50

7

A Four-State Conversation Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

51

8

A Six-State Conversation Model

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

52

9

Probability Distribution of Time Spent in a State . . . . . . .

53

10

Six-State Conversation Model with ur and 3 Parameters

53

11

Talking On/Off Patterns versus Time for a Single Speaker in a Conversatio n.

12

Time in Each State for Brady's Data[32] and the Switchboard Speech Corpus[34] 58

13

Time in Each State for 3 Calls from the Switchboard Corpus

. . . . . . . .

61

14

Simulated Talking On/Off Patterns versus Time for a Single Conversation

with a Pair of Average Speakers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

63

Real Talking On/Off Patterns versus Time for a Single Conversation with a

Pair of Average Speakers . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

64

Simulated Talking On/Off Patterns versus Time for a Conversation with a

Dominant Speaker . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

66

Simulated Talking On/Off Patterns versus Time for a Conversation with an

Alternating Protocol . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

67

18

Agreement and Disagreement Time with ta Shorter than State Lengths

76

19

Agreement and Disagreement Time with ta Shorter than State Lengths

76

20

Test Network for Experimentation

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

79

21

End-to-End Delays for 128-bit, Uncompressed AES and Clear Communication with Varying Levels of Traffic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

83

15

16

17

. . .

57

22

Loss Rates for 128-bit, Uncompressed AES and Clear Communication with

128 Kbps Bandwidth and Varying Background Traffic (End-to-end throughput) 84

23

Loss Rates for 128-bit, Uncompressed AES and Clear Communication with

128 Kbps Bandwidth and Varying Background Traffic (Actual Packet Sizes)

85

Introduced Loss Rates for Clear and Encrypted Communication . . . . . . .

86

24

11

25

Loss Rates versus Bit Error Rates for Clear and Encrypted Communication

87

26

Disagreement Factor for Varying Two-Way Latencies . . . . . . . . . . . . .

92

27

Expected and Observed Loss Rates versus Bit Error Rates for Clear and

Encrypted Communication . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

94

12

List of Tables

1

Sample and Bandwidth Information for Various Voice Codecs . . . . . . . .

20

2

The MOS Quality Scale . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

44

3

Brady's Parameters for the Six-State Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

54

4

Statistics of Brady's Parameters for the Switchboard Data . . . . . . . . . .

59

5

Statistics of Brady's Parameters for the Switchboard Data with Buffer . . .

59

6

Brady's Parameters for a Dominant and Passive Speaker . . . . . . . . . . .

65

7

Brady's Parameters for an Alternating Protocol . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

68

8

Characteristics used to Simulate Various Airborne Links . . . . . . . . . . .

78

9

Baseline Per-Packet Delays for Various Encryption Algorithms in Openswan

81

10

Factors Contributing to R score for Various Links . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

97

13

1

Introduction

The rapid growth and scope of the Internet has had a tremendous impact on the way

people communicate. E-Mail and instant messaging have revolutionized the speed and

cost of written correspondence, and allowed people separated by great geographical

distances to write to each other much faster and cheaper than previously possible.

Phone conversations, on the other hand, have not experienced a significant change

with the advent of the Internet until only recently. In the past five years, though, the

spread of technology that allows communicating over the Internet, called Voice Over

IP, has demonstrated that this is rapidly changing.

The slow adoption of Voice Over IP, or VoIP, has largely been a result of poor quality

of service. The Internet is subject to delays and bandwidth limitations that, until

recently, have made VoIP unattractive to typical users. In sending e-mail, or browsing

websites, delays of a few seconds do not significantly hamper a user's experience, but

in a verbal conversation it makes things quite difficult.

A second challenge facing VoIP is security. The traditional phone system, the public

switched telephone network or PSTN, consists of a series of dedicated circuits that are

really owned by a few select bodies. This makes it difficult for others to "tap in" and

listen to particular calls. The Internet, on the other hand, spans countless switches,

lines, and routers, and in any given connection is very difficult to know exactly where

data is being sent, or who can see it. For this reason, the privacy that people have

come to expect from their communications is not guaranteed in VoIP systems.

Providing privacy in an Internet setting generally relies on mathematical cryptographic algorithms that encode data before it is sent out in a way that only the

intended recipient can decode. These algorithms, however, introduce an overhead in

both time and bandwidth. If people are to have an equivalent level of privacy from

VoIP systems as that provided by the PSTN, the overhead introduced by applying

security features must not reduce the conversation quality below the point of usability.

The main goal of this research is to develop a methodology for objectively estimating

the quality of VoIP communication in a given network environment. Security should

be incorporated into this model, as well as unique network characteristics that may

arise in less than ideal situations. Some Internet communication runs over links with

limited bandwidth or above average latency, and it is important to understand how

VoIP performs in these environments. Of particular interest is the performance of

VoIP over encrypted wireless airborne networks.

To explore the feasibility of secure VoIP in various network environments, an understanding of behavior of VoIP systems is first necessary. The size and rate of packets

sent, as well as the on/off spurts of VoIP speech are studied so that an accurate

model of a VoIP user can be developed. There has been quite a lot of exploration of

VoIP traffic generation in the commercial sector, with emphasis on testing the limits

14

of infrastructure capacity. These commercial tools, however, such as Hammer VoIP

Test Solution [1] and IxVoice[2], do not use complex conversational models, but rather

send pre-generated traffic streams, or use very simple exponential on/off models[37].

A second task of this thesis is to explore the various ways of providing security in

an Internet setting. There are several ways to ensure security, including different

encryption algorithms, and at which network layer they are applied.

Finally, a metric for conversation quality that incorporates network characteristics

and security implementation should be developed. Conversation quality is largely a

subjective concept. Different people may have different standards of what a "good"

quality conversation is. Being able to objectively estimate voice quality is essential

in estimating the performance of a particular proposed VoIP setup. The focus of this

thesis was on the evaluation of conversation quality, and the impact of security and

unfavorable network links on call setup was not considered, although some information

about the latter is included for completeness.

Section 2 provides some background information about the public switched telephone

network and the Internet. Sections 3 and 4 present VoIP in more detail, discussing

it in a historical context, providing implementation details, and reviewing the protocols involved. Section 5 provides an overview of Internet security, with emphasis

on security's role in the context of VoIP. It also explains why we chose IPSec as the

security layer for our experiments.

Section 6 gets into the various methods of evaluating speech quality, and justifies

the choice of the International Communications Union's E-Model as an appropriate

performance measurement tool. In Section 7 the techniques for conversation modeling

are explored, as well as a methodology for adapting a PSTN conversation model to

mimic VoIP behavior.

The main focus of this thesis is in Sections 8 and 9. In Section 8 the Z-Model is

introduced, a computational model, based on the E-Model, that incorporates security

and fine-tunes the E-Model in the context of VoIP systems. Section 9 discusses the

experiments performed in designing and evaluating the Z-Model as an appropriate

tool for measuring VoIP quality.

Finally, Section 11 discusses the limitations of this research and explores areas for

further study. Section 12 offers some concluding remarks.

15

2

Background

Before delving into the world of VoIP and security, it is appropriate to know a little bit

about VoIP's predecessors. This section will discuss the telephone and the network

built to support telephony: the public switched telephone network. It will also briefly

discuss the advent of the Internet, the network VoIP was built to run over.

2.1

Before VoIP: Telephones and the Public Switched Telephone Network

The Internet has connected people further and faster than ever before in history. But

before the Internet, the telephone was the global method of communicating across

large distances. The first voice transmission was sent by Alexander Graham Bell in

1876[3]. Bell did not have a phone number to dial or an e-mail address, he simply

picked up the phone and the person on the other end could hear what he said. For

a long time, this was the model used by the telephone: a user had to have a direct

connection to whoever he wanted to call.

As phones became more widespread, a new model was required in which each person

had a connection to a central switch. To reach someone else, a caller would ask

the operator of the switch to physically connect the appropriate lines, which would

establish a circuit for the duration of the call[3].

Over time the shape and mechanisms of the phone network changed. Operators were

replaced by a signaling code (i.e. your phone number) that allowed calls to be routed

and connected automatically. As the network grew, it developed hierarchical layers

of switches, each one supporting more traffic. The resulting network is known as the

public switched telephone network (PSTN).

The PSTN is excellent at providing high quality communications. Except in times

of extreme usage, such as a natural disaster or holiday, when many people are trying

to communicate at the same time, people can reach each other whenever they want.

Typically the PSTN is up 99.999% of the time[4]. In addition, the typical sound

quality of PSTN calls is very good. This is because the PSTN calls are circuitswitched. That means that a dedicated circuit is created during the setup phase of

the call, and this circuit continues to serve the call in an exclusive manner until it

completes. Each call is guaranteed a fixed amount of continuous bandwidth, no more

and no less, for the duration of the call.

Circuit-switching also has its disadvantages. First of all, it is bandwidth inefficient;

the circuit is tied up by a conversation, regardless of whether or not either of the

parties happens to be talking. Additionally, this fixed bandwidth makes it difficult to

add new features. Typically, a single home has a 56-kbps phone line, which is simply

16

not enough bandwidth to support Internet, phone, and video at the same time[3].

The alternative to a circuit-switched network is a packet switched network, in which

each chunk of data is individually routed. Packet switched networks, such as the

Internet, make more efficient use of bandwidth. For this reason, the people who hope

to converge the phone and data networks believe that voice should be migrated to

packet networks and not the other way around. As it currently stands, many people

still use the phone network and a modem for data transfers, such as e-mail and web

browsing. As the demand for data and bandwidth continues to increase, the use of

the PSTN for data becomes increasingly infeasible, and the need to migrate voice to

the data network becomes apparent.

2.2

The Internet

In this section we provide a brief history of the Internet. It is not meant to be an

exhaustive study of the Internet details, but rather a context for comparing VoIP to

PSTN calls.

The origins of the Internet go back to a 1969 project of the U.S. Department of Defense. At that time, the PSTN was the only available nation-wide communications

system. The government realized that because of its dependence on circuit switching, switching stations could be targeted during an attack and effectively take down

communication channels of an entire region[5]. The government wanted to build a

network that would dynamically route each piece of traffic (called packets) depending

on the availability of links. The result of this project was the ARPANET, which

would later develop into the Internet[6].

At the heart of the ARPANET was packet switching. This was a way that allowed

data to travel from one point to another in the network without setting up a connection or establishing a fixed path. Each node on the network had its own unique

address, known as an IP (for Internet Protocol) address. Then each packet could be

labeled with a source and destination address, and the routers could look up where

to send the packet to reach that address. One problem with this protocol is that it

is unreliable; packets are not guaranteed to reach their destination. For this reason,

other protocols run over the Internet, such as Transmission Control Protocol (TCP),

and User Datagram Protocol (UDP), that can provide varying levels of connection

control. These protocols are discussed in Section 4.2.

There are several nice things about packet switching. One is that it allows bandwidth

to be used only when it is needed. Low bandwidth applications, such as e-mail, can

share links with voice or video at the same time as long as bandwidth supports it.

Packet switching also allows data to be dynamically routed, so connections can be

maintained even as intermediate links and hosts go up and down. Dynamic routing

also allows bandwidth to be spread across different links in times of congestion.

17

There are some disadvantages to packet switching as well. In particular, it is difficult

to guarantee a particular level of service to users; a task that is readily accomplished

by circuit switched networks. Additionally, the Internet was designed such that the

majority of network control is placed at the endpoints. This can cause network

management to be a difficult task.

Despite its shortcomings, the Internet has experienced incredible growth since the

development of the ARPANET. As recently as 1983 there were fewer than 600 registered hosts on the ARPANET, most of whom were universities and military research

sites[5]. Now the Internet has countless hosts and supports incredible volumes of

traffic. Thus, there is plenty of room on the Internet for voice traffic.

18

Voice Over IP

3

Voice over IP (VoIP) is the transmission of voice data over packet-switched networks,

such as the Internet. This section provides an overview of VoIP technology and discusses why VoIP is an important topic to study. Section 3.1 provides a quick overview

of VoIP systems. Section 3.2 discusses the historical context of VoIP. Section 3.3 discusses the motivation behind implementing VoIP instead of traditional PSTN technology, and Section 3.4 discusses some of the challenges facing VoIP, several of which

are addressed in the rest of this thesis.

3.1

System Overview

A typical VoIP architecture is shown in Figure 1. Each user has a device, called a

"Voice Terminal" that performs the operation of translating speech to data packets

that can be sent over the Internet. Voice Terminals can be a stand-alone piece of

hardware (known as an IP phone), software running on a PC, or a regular phone

running through an adaptor and plugged into the Internet.

Analog to

converter

Dt

copesn

Alice

RTP Packet

UOP Packet

Internet

[T Pce]

Bob's Voice Terminal

Alice's Voice Terminal

(Software or Hardware Phone)

Figure 1: A Typical VoIP Setup

The first element of the Voice Terminal is an analog to digital (A/D) converter.

This device takes in the analog audio signal, either from a phone handset or PC

microphone, and converts it to digital data that can be processed by a computer

chip. Once the speech has been digitized it is usually compressed by a device or

program known as a codec. Compression allows the data to take up less memory, while

sometimes resulting in loss of information and quality. There are several standard

codecs for voice that offer varying levels of compression and quality, and an overview of

the most popular codecs can be found in Table 1[16]. In addition to being compressed,

19

Codec and

Bit

Rate

(Kbps)

G.711 (64)

G.729 (8)

G.723.1 (6.3)

G.723.1 (5.3)

G.726 (32)

G.726 (24)

G.728 (16)

Codec

Sample

Size

(Bytes)

80

10

24

20

20

15

10

Codec

Sample

Interval

(ms)

10

10

30

30

5

5

5

Voice

Payload

Size

(Bytes)

60

20

24

20

80

60

60

Voice

Payload

Size

(ms)

20

20

30

30

20

20

30

Packets

Per

Second

(PPS)

50

50

34

34

50

50

34

Bandwidth

MP

or

FRF.12

(Kbps)

82.8

26.8

18.9

17.9

50.8

42.8

28.5

Bandwidth

Ethernet

(Kbps)

87.2

31.2

21.9

20.8

55.2

47.2

31.5

Table 1: Sample and Bandwidth Information for Various Voice Codecs

the codec also breaks the audio into data values, known as samples, taken at small,

discrete timesteps apart from each other. The exact timestep and size of these samples

depends on the codec used.

The compressed audio data is then wrapped inside a Real-Time Protocol (RTP)

packet[71]. Depending on the codec, one or more samples will be put inside a single

RTP packet. The purpose of the RTP is to provide information on the codec used,

as well as additional sequencing and timing information that allow the allow the

stream of packets to be converted back to audio. Details of how this is accomplished

are discussed in Section 4.2.4. The RTP packet is then put into a User Datagram

Protocol (UDP) packet[69], to be sent over the Internet. UDP provides information

about source and destination addressing so that routers in the Internet that handle

the packet know where to send it. The choice of UDP over TCP is discussed in

Section 4.2.2.

The packet is then shipped over the Internet (or, in some cases a Local Area Network

(LAN)) to the receiving user. This user has his own Voice Terminal that can perform

the inverse operations on the packet. This involves first removing the UDP headers

and parsing the RTP data to determine the codec and ordering of the packet. Then,

the packet is decoded with the appropriate codec, and is passed through a digital

to analog (D/A) converter, where the resulting analog signal can be played (either

through a handset or a computer's speakers). Because both parties in a two-way

conversation need to encode and decode the data, both functions are needed in each

host's voice terminal.

3.2

History and Growth

Although VoIP has recently emerged as one of the hottest topics in technology, it

has actually been researched and developed for quite a long time. In 1978 the first

packet-switched teleconference was held on the ARPANET, with members including

20

Cliff Weinstein of MIT's Lincoln Laboratory[8]. Weinstein et. al. later published

a paper describing sending speech over packet networks in 1983[9]. Additionally,

the first functional VoIP software was released by VocalTec Inc. in 1995[10]. This

software was designed to run on a PC, but, unfortunately, insufficient processor speed,

Internet bandwidth, and other factors prevented VoIP from being a viable option to

PSTN telephony.

Since then, however, advances in processor speeds and a drastic increase in Internet

bandwidth and reliability have allowed VoIP to be a reasonable alternative to PSTN.

As a result, VoIP has experienced tremendous growth. This can be seen in the rate

at which Cisco, the leading manufacturer of IP phones, has sold its products. Cisco

shipped its 1 millionth phone in August of 2002, representing three and a half years

of sales. It shipped its 2 millionth phone just 12 months after that, in July of 2003,

and its 3 millionth phone in April of 2004, only 8 months later[11].

Cisco is not the only company reflecting the growth in this industry. According to

research done by the Yankee Group, 54 percent of businesses are currently testing or

evaluating the potential of VoIP[13]. Another study, by Juniper Research, estimates

that by 2009, 10% of all US households and 40% of business lines will be using VoIP.

They also estimate that the global VoIP market in that year will be $32 billion[14].

From this information it seems clear that VoIP is an important industry and technology. The next section discusses motivations for switching to VoIP. Section 3.4 goes on

to discuss some problems that should be addressed before employing a VoIP system.

3.3

Motivation

The largest reason why many people and businesses are switching from PSTNs to

VoIP is cost. The discrepancy of cost between these technologies lies in the inherent

difference between circuit and packet switched networks. Making a PSTN call requires "renting" bandwidth on a circuit controlled by a few large corporations for the

duration of the call. Internet bandwidth, on the other hand, is a largely underutilized

resource, and typically users are charged a fixed amount for connectivity regardless

of bandwidth use. This makes VoIP extremely cheap. Additionally, while there are

many regulatory charges for long distance and international phone calls over PSTNs,

packet switched networks, like the Internet, are currently completely unregulated[17].

As a result, many sites exist today that offer free VoIP to consumers (Skype and

EarthLink are two), while countless other providers offer unlimited long-distance dialing over IP for a small monthly fee (AT&T, CableVision, Net2Phone). Since IP

bandwidth is extremely cheap compared to PSTN lines, this is an economically sound

option for both providers and users of VoIP systems.

For corporations, the switch to VoIP can be even more economical. Since VoIP

uses the same underlying architecture as data networks, a complete switch to VoIP

21

can eliminate the need for a company to have a separate voice network, saving cost

and resources. This consolidation of networks makes internal phone lines obsolete, a

change that could save companies up to 20% when compared to PSTN[15].

There are also non-economic advantages to VoIP. One advantage emerging recently

is the elegance and philosophy of "everything over IP." Merrill Lynch and Vonage

have recently released a study[18] that claims that VoIP is a first step towards a day

when all communication technologies (Internet, phone, television, radio, etc.) will

run over IP. This convergence has economic advantages, but also creates simplicity in

merging different mediums; only one set of communication lines and protocols would

be necessary.

VoIP also allows users to be free of ties to a physical location. In this way, VoIP

resembles a cellular phone; a user can plug his IP phone into any Internet jack in the

world and have his phone respond to the same number. Wireless IP networks make

this comparison even more viable. Another benefit is that telephone addresses are no

longer confined to 10-digit numerical codes, but could take nearly any form (e-mail

addresses with a special marker, for example).

Despite these advantages, there are still several problems with VoIP that need to be

addressed. These are discussed next.

3.4

VoIP Deployment Challenges

VoIP, like any new technology, comes with a set of challenges that must be addressed before it can be widely and safely used. These challenges fall into three main

categories: setting up a VoIP infrastructure capable of interfacing with the existing phone network and supporting VoIP systems from different vendors, maintaining

conversation quality that users are accustomed to, and providing security through authentication and privacy. These challenges are discussed individually in the following

sections.

3.4.1

Infrastructure Requirements

The most obvious problem when employing a new communications technology like

VoIP is building an infrastructure that will allow it to run smoothly and integrate

with existing technologies. Luckily this problem has, for the most part, already been

addressed.

One nice thing about VoIP is that it runs over IP, so the existing Internet backbone

can be used to transport data and new lines are not necessary.

For addressing, call setup, and interfacing with the PSTN, several protocols have been

suggested, with two of them, H.323 and SIP, emerging as the most popular[64]. At

22

some point a standard for VoIP will have to be accepted, but until then the various

protocols must be able to interface not only with each other, but also with the existing

PSTN. For this purpose there exist boxes, known as gateways, that allow translation

from IP to PSTN for various VoIP signaling protocols.

Thus, two very important aspects of a VoIP infrastructure are already in place. First,

a VoIP network can run almost exclusively as a layer over IP, so the connecting

network is already set up. Second, this network can readily interface with the PSTN,

so users can switch to VoIP one at a time without being disconnected from the

existing phone network. This allows VoIP to be incrementally deployable, a crucial

characteristic if it is to be incorporated smoothly into the telecom architecture.

3.4.2

Factors Affecting Conversation Quality

A second major concern with VoIP has been the issue of conversation quality. Users of

any kind of telephone system are accustomed to a certain level of quality, below which

the usability of the system quickly degrades. It is therefore important to assure that

the conversation quality provided by VoIP systems equal to that of PSTN systems.

Until recently this has been a difficult task.

There are several factors that can influence conversation quality. One is the problem of

delay. Sources disagree on the acceptable amount of delay before which quality rapidly

deteriorates, but most place this value somewhere between 100 and 400ms[17, 53].

Delays can come from a number of sources. Computationally, there are delays at each

step of the way. The A/D and D/A conversion take time, as does compression by

the codec, packetizing and depacketizing the data, and decompression by the codec.

Clearly, these delays are directly related to the processor speed of the voice terminals.

For modern computers and IP phones they are typically quite small, but for a long

time they made VoIP unusable[17]. Additionally, data routed over the Internet can

travel through several routers, each of which may have a packet queue that can add

to delays. Finally, there is also a delay associated with sending a signal over a wire

that is proportional to the distance and the speed of light. This is a physical barrier

that cannot be avoided or significantly reduced for VoIP or PSTN conversations.

A second problem facing VoIP is that of bandwidth. Any live streaming application,

by nature, will require a significant amount of bandwidth. Even after compression

and employing Voice Activity Detection (which prevents packets from being sent in

periods of silence), nearly all VoIP applications require at least 20 Kilobits per second

of bandwidth on the network[16]. Only recently have most homes and businesses had

this kind of consistent bandwidth at their disposal.

Another factor that affects VoIP quality is jitter, which is the variance of interarrival

times between packets. For a real-time application such as VoIP, it is important

23

that packets arrive in a relatively smooth and uniform rate. Jitter can drastically

reduce conversation quality if measures are not taken to counter it. In many cases

this problem can be mitigated through the use of a jitter buffer[50].

Several other factors affect VoIP quality, including packet drops and transmission

errors over the network. With the combination of all of these factors, it has turned out

that only in the last decade or so have computer systems and a network infrastructure

capable of supporting high-quality and ubiquitous VoJP been in place[58].

There are several ways of estimating conversation quality. One model that has been

introduced by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) is the E-Model

[53], which attempts to determine a quality score based on delay, jitter, codec, and

several other transmission factors. Evaluating conversation quality is the subject of

Section 6, and the E-Model details, as well as an overview of other quality models,

can be found there.

3.4.3

Security

In addition to challenges concerning conversation quality, a second concern for VoIP

relates to security. In contrast to the PSTN, which is largely considered to be a

secure, private network, the Internet is open to eavesdropping, impersonation, and

denial of service (DoS).

A key problem with VoIP security is that many of the protocols and techniques used

(see Section 5.1.2) to protect data networks have not been widely used or tested in

VoIP networks. Firewalls, for example, are known to create problems with VoIP callsetup protocols[27]. Additionally, adding security inevitably increases packet sizes

(thus bandwidth) and delays, as the mathematical encryption algorithms take time

to be performed. Security issues with VoIP are discussed in more detail in Section 5,

and how security affects conversation quality is the subject of Section 8.

24

4

VoIP Implementation Details

Section 3.1 provided a brief overview of Voice over IP systems. This section expands

on that topic in more detail. In particular, it addresses the various protocols used

in VoIP systems. These break down into two main categories: protocols used for

setting up calls and building a VoIP infrastructure (discussed in Section 4.1), and

protocols for transporting the speech data over the Internet (Section 4.2). While the

focus of this thesis is on conversation quality, the call setup and teardown protocols

are discussed for completeness.

4.1

Call Setup Protocols

One of the most important needs for VoIP systems was a well-defined and accepted

protocol for managing the VoIP infrastructure. Since VoIP devices are associated with

an IP address that may change over time (if a laptop user plugs into the Internet from

two different locations, for example) there must be a dynamic process of associating

a particular user with an IP address. Additionally, there needs to be an established

signaling process that allows users to call each other, be connected, receive busy signals, and leave voice-mail; anything users expect from traditional phones should be

supported by VoIP. Finally, there should be a well-defined way to interface between

VoIP and traditional PSTN phones and networks. Several protocols have been introduced to accomplish these tasks, with the two most important ones being H.323 and

Session Initiation Protocol (SIP).

4.1.1

H.323

H.323 was the first widely used standard for VoIP[17]. The first version of H.323

was developed and endorsed by the International Telecommunications Union in 1996,

and subsequent versions have been released in 1998, 1999, 2000, and 2003[7]. There

are four basic components in an H.323 system, a terminal, gateway, gatekeeper, and

multipoint control unit.

The terminal is the endpoint device that provides a user interface to the system,

similar to the voice terminal block in Figure 1. Terminals can be a dedicated piece of

hardware known as an IP phone, a software program running on a personal computer

(PC), or a normal telephone running through a network adaptor.

The gateway is a device that provides a protocol conversion between the H.323 IP network and other types of networks (PSTNs, for example). This allows the H.323 phones

to communicate with devices running different protocols, such as PSTN phones, or

VoIP devices running over a non-H.323 protocol (e.g. SIP). Gateways are maintained

by a VoIP provider, or by a company to allow their users to interface with other

25

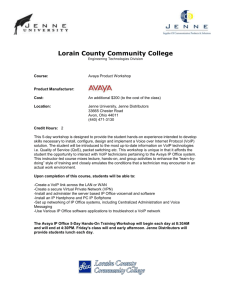

Calling Party A

TA-.SYN 3alling

C

98.76.54.32

, provides

TCP Pert

trty

a

TCP Port

H.225 SETUP

ALERT

PA11-225

B

1234ek

ta

dg6789

A

P2

11.225 CONNECL TCP P.,

TCP Port

___________

U8

wpRSYN

T,.245 TrminatConptilut.

party)

eb.st.h

Set

party)

Set

ta ails fithe

Hf246 t

14.245 6ndwmnal Capahilitive Set ACI( AIMacicr

SHt ACK tB Srt.

bs

Capalsiti.

11.245 Tera

iL 246 Open L.~*.. C~ae.'.I (44*.

r

Op.. Lthe

d24

rt biis fe..ue'

pTatPoeria)

0...)

Aditnay

yp

tp,

a

a..

d(

conet

H.

snt

ort

spDPaPt

hrougalls them

route

Figure 2: An H.323 Call Setup

communication networks.

The third H.323 device, the gatekeeper, provides call control, bandwidth management, and address translation for connections between H.323 endpoints. Calls are

initiated through gatekeepers, which are responsible for translating a phone number

to an IP address, and also may monitor call times for billing and tracking purposes.

Gatekeepers, again, are maintained by a provider or corporation, and users simply

route calls through them.

The final device, known as a multipoint control unit, enables three or more terminals

or gateways to establish a multipoint conference. Three-way calls are currently outside

of the scope of this thesis, and so details of the multipoint control unit are not

discussed.

One major drawback of H.323 is that many control messages and protocols are used

to initiate and terminate calls. Figure 2 shows the control messages required to setup

an H.323 call between two parties. It can be seen that H.323 relies on several other

protocols including H.225 (to set up the connection), and H.245 (to determine the

capabilities of each user's terminal). Additionally, connections on two separate ports

are required for the setup of a single call.

Another criticism of H.323 is that the protocol is binary-encoded, that is, it encodes

information in numbers as opposed to text. This encoding is frustrating for programmers debugging H.323 applications because it is difficult to easily observe what the

problems are. The binary encoding also makes H.323 less extensible, as information

26

must be contained in a very specific part of the packet with a fixed size. For these

reasons many people have recently moved away from H.323 and accepted SIP as the

standard for VoIP.

4.1.2

Session Initiation Protocol (SIP)

Session Initiation Protocol[72], commonly known as SIP, has recently become the

accepted standard for multimedia Internet applications, including VoIP, for the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF). It was developed and accepted by the IETF, a

body that oversees many of the Internet's standard protocols, as part of the Internet

Multimedia Conferencing Architecture. In addition to being used for VoIP, SIP can

also be used for video conferencing, instant messaging, and chat.

In SIP each user is associated with an address known as a uniform resource indicator

(URI). The URI (sometimes called a SIP URI, or SIP address) is analogous to uniform

resource locators (URLs) of websites, with the key difference that they are meant to

be dynamic[22]. URI's are not meant to be tied to a particular physical device, but

to a logical entity that might move or exist in multiple places.

A SIP architecture has several similarities to an H.323 architecture. Two similar

elements are SIP user agents (UAs) and SIP gateways. A SIP UA is analogous to an

H.323 terminal; it is a hardware or software device that allows a user to make VoIP

calls using SIP. SIP UAs can take the form of dedicated hardware phones, networkadapted analog phones, or software applications running on an Internet-enabled PC.

SIP gateways are also analogous to H.323 gateways; they provide translation between

protocols. Two common gateways are SIP/PSTN gateways, which allow SIP devices

to interface with traditional phone systems, and SIP/H.323 gateways, which interface

SIP and H.323 devices together. Like H.323 gateways, these are part of the infrastructure backbone, and are generally maintained by service providers or corporations.

SIP architecture also requires a number of SIP servers, devices that handle SIP messages, and each one serves a different function. The three types of SIP servers are

proxy servers, redirect servers, and registration servers. They are discussed below.

Proxy Servers

The role of a proxy server is to handle SIP messages on behalf of SIP user agents.

Proxy servers usually have access to a database or location service to help determine

what to do with the request. For example, a UA might try to initiate a call to a person

who's SIP URI is alicedbigcompany.com. The UA sends a SIP INVITE request to

a proxy, and the proxy attempts to determine the IP associated with Alice's address

by querying its database or location service. The proxy server then forwards the

request to wherever it determines the best location for Alice is, or responds with a

"not found" error message. Proxies, in general, do not create new messages, they

27

merely forward and respond to requests as they see fit.

Redirect Servers

A redirect server is a SIP server that responds to requests, but never forwards them.

Like the proxy server, it usually queries a database or location service to determine an

appropriate response, but unlike the proxy it will never forward a message. Redirect

servers usually inform the requesting UA of the location of someone, but leave it up

to the UA to contact that location on its own.

Registration Servers

A registration server, or registrar, only accepts one type of SIP message, a SIP REGISTER request. The registrar then keeps state of the users registered to it for a

particular domain, allowing the proxy and redirect servers to query it for location

information. Registration servers usually perform user authentication, although this

isn't required. Authentication ensures that only valid SIP users in the registrar's

domain are registered and serviced, and prevents outside users from placing and receiving calls through another domain's servers.

While each server is logically separate from the other two, any and all three servers

can reside in the same physical location, and many open-source and commercially

available SIP servers perform all three functions[27].

One advantage to SIP is that it is a text-encoded protocol. This means that the information is sent over the Internet as human-readable text. Other text-based protocols

include Hyper-Text Transfer Protocol (HTTP) and Simple Mail Transport Protocol

(SMTP), which World Wide Web and e-mail systems use, respectively[73, 74]. The

advantage to a text-based protocol is that it is much easier to program, analyze, and

debug. A simple traffic sniffing tool can be used on the network to easily understand

what information is being sent - a task not nearly as straightforward in H.323 systems.

Another advantage is that, SIP call setup is quite simple, as can be seen in Figure 3.

This figure, as compared to Figure 2, represents all the signaling required for a complete call (Figure 2 is only an H.323 setup), and shows a call being routed through a

SIP proxy server. SIP calls only require the establishment of a single TCP connection, and SIP can even bypass TCP and run entirely over UDP (a discussion of TCP

versus UDP can be found later in this section). In SIP, all of the codec negotiation

is done in the INVITE and OK messages, bypassing the need for the series of H.245

"terminal capabilities" messages seen in Figure 2.

4.1.3

SIP versus H.323: A Comparison

Several sources[22, 27] have provided a comparison of SIP and H.323. Both protocols

have their own merits, which are discussed here.

28

Bob

Proxy Server(s)

Alice

INVITE Alice

INVITE Alice123.45.67.8

from Alice@123.45.67.8

rA

4.OK

OK fromn Alicve 123.45.67.9

ACK Alice with route

Alice a123.45.6 7.8

BRY 1 A Iicc

ACK AliceI23.45.67.8

123. 4-5.678

E

OK

BYE Alice

123.45.67.8

OK

o

Figure 3: A SIP Call Setup and Takedown

The difference in H.323 and SIP is largely a product of where they were developed.

H.323 was developed by the International Telecommunications Union (ITU), and so

it largely resembles other telecommunications protocols. H.323 even reuses parts of

ISDN signaling, reflecting its roots in the telecom industry. SIP, on the other hand,

was designed by the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF), and so it resembles

other Internet protocols like HTTP and SMTP.

One aspect of SIP that is highly advantageous is its use of a common universal

addressing scheme: the SIP URI. Because of this it allows a single SIP user to have

different SIP-enabled devices at multiple end-points that are all associated with that

user. A SIP phone, videoconferencing tool, and instant messaging client could all

be tied to a single URI; one of the reasons SIP is said to be more scalable than

H.323. Additionally, SIP's text-based encoding, when compared to H.323's binary

encoding, is an advantage in both clarity and extensibility. New fields can be added

incrementally to SIP, a task that is more difficult to accomplish in H.323.

It is unclear when (if ever) a true standard will emerge, but while H.323 arrived and

was widely implemented first, SIP's simplicity and versatility have caused it to gain

great momentum in the IP telephony world. SIP has now become widely backed

by major companies including Microsoft, Cisco, and Nortel, and appears to be the

growing trend.

An interesting side note about the two protocols is that as time has progressed, they

have grown more and more alike[22]. For example, SIP was designed to support DNS

(domain name service) from the start, a feature that was added in later versions of

29

H.323. Conversely, a system similar H.323's multipoint control units, which allowed

for 3-way calling, is currently being added to SIP.

Alan Johnston[22] provides a nice summary of the current situation. "While there

are some similarities between the protocols in call setup, and some niche markets that

H.323 currently dominates, SIP, with its text encoding, presence and instant message

extensions, and Internet architecture, is poised to be the signaling and 'rendezvous'

protocol of choice for Internet devices in the future." For these reasons, SIP was

chosen as the protocol to use in our experiments.

4.1.4

Others

SIP and H.323 are not the only protocols that have been proposed for IP telephony.

Others include Megaco, MGCP, and Skinny. While these protocols are used in some

areas today, it is believed that either SIP or H.323 (or both) will become the standard

for VoIP and so a detailed discussion of these protocols is not provided here. Please

refer to the references[78, 79, 67] for more information about these protocols.

4.2

Transport Protocols

While SIP and H.323 perform call setup and takedown signaling, they do not provide

any means of actually transmitting information over the Internet, nor do they handle

the media streams containing the actual audio data. For this task several existing

protocols are employed, including IP, UDP, TCP, and RTP. Both SIP and H.323,

for example, must run over either TCP or UDP. Additionally, the audio data of the

conversation uses RTP running over UDP for delivery. Finally, all of these protocols

run over IP. An explanation of what these different transport protocols provide is

found below.

4.2.1

Internet Protocol (IP)

Internet Protocol[68] (IP) is used to route packets across a data network, such as the

Internet. It provides connectionless, best-effort packet delivery, meaning that packets

might be lost, delayed, arrive out of sequence, or contain errors.

Each location on the network is associated with a particular address, known as an IP

address. The current most-employed standard for IP addresses is IP version 4 (IPv4),

in which addresses consist of four numbers between 0 and 255, separated by periods.

123.45.67.8 is an example of an IPv4 address, as is 11.0.0.255. A new version of IP,

IP version 6 (IPv6) has been developed by the IETF to allow for longer addresses,

because the IP address space is rapidly running out. The increased address space

30

provided by IPv6 is necessary if every telephone in the world is to have a unique IP

address. That said, IPv6, while an important emerging technology, is largely outside

the scope of this document, and we performed all our experiments with the more

common IPv4 protocol.

IP addresses are assigned by the Internet Assigned Number Association[22] (IANA),

and so they are globally unique. This ensures consistency; packets destined for a

particular unicast address should always arrive at one and only one unique machine.'.

An IP address is a lot like a street address. In the same way that any piece of mail

with a specific address on it can be dropped in any mailbox and should find its way to

that address, any IP packet with a specific destination IP address, sent to any router

on the Internet, should find its way to that computer.

4.2.2

User Datagram Protocol (UDP)

User Datagram Protocol[69] (UDP) provides a small step up in complexity from

IP. It is also a connectionless, best-effort protocol, meaning packets can be lost or

dropped, but it provides a checksum, allowing errors to be detected. Additionally,

UDP specifies not only an IP address, but also a port. Certain communications run

over specific, well-known ports (for example, HTTP uses port 80, and SIP uses port

5060). In this way, UDP allows multiple logical channels of communication to exist

between two computers. In the case of VoIP, SIP could be handling the call setup

over port 5060, while the actual data streams are traveling over some other (usually

determined at call-setup) port.

4.2.3

Transmission Control Protocol (TCP)

Transmission Control Protocol[70] (TCP) also runs over IP, but provides the reliability and guaranteed delivery of data that IP and UDP do not. It does this by

using acknowledgements and sequence numbers. Every TCP packet that is sent has

a header representing which bytes of the overall stream of data the packet represents.

This header allows the receiver to recognize when information is missing and ask the

sender to resend. It also allows the receiver to reconstruct information in the correct

order, even though packets may arrive out of order.

TCP is a good transport protocol to use when guaranteed and reliable delivery is

required. Most traffic, including World Wide Web, e-mail, and File Transfer Protocol

(FTP) use TCP. A problem with TCP, however, is that it can make things slow.

Retransmission takes time (usually more than double the round-trip time (RTT)

between sender and receiver) and in live streaming applications (like VoIP) a delay

'Actually, this isn't always the case because of dynamically assigned IP addresses and network

address translators (NATs), but can generally be considered true.

31

as small as a second can severely detract from conversation quality. Additionally,

TCP has problems with long latencies, since it drastically reduces the transmission

rate when packets are lost. For these reasons, TCP is generally not used for media

streams, although it can be used for call-setup. As mentioned previously, currently

SIP and H.323 support delivery over both TCP and UDP.

4.2.4

Real-Time Protocol (RTP)

VoIP and other media streaming applications are a unique type of traffic with very

specific requirements. More than any other service these applications are extremely

time-sensitive. Delays larger than a few fractions of a second are simply unacceptable.

Fortunately, these applications do not need guaranteed delivery of every packet. Audio and video applications can usually interpolate a value for a missing data point and

end-users likely won't notice a loss in quality. A final requirement of these applications

is that ordering should be preserved. Users don't want to hear words out of place in a

conversation. Moreover, many voice and video codecs use differences rather than absolute values to encode data, and a reordering of information can make it completely

useless. To summarize, VoIP requires a quick delivery of data along with ordering

information, but doesn't require guaranteed delivery. Real-Time Protocol[71] (RTP)

was developed to meet these characteristics.

RTP runs over UDP, and is therefore a connectionless, best-effort protocol. This

ensures the fastest possible delivery over the Internet, and also means that some

packets will be dropped or arrive out of order. In addition to the UDP checksum,

which alerts the receiver if the data in the packet is contains errors, it also provides

several multimedia-specific features.

One of these features is sequencing. As mentioned above, sequencing is important

in streaming applications. Typical VoIP applications actually hold on to packets

for a certain amount of time (known as the jitter buffer, and mentioned earlier in

Section 3.4.2) before delivering them to the end-user. This allows some packets that

arrive late or out of order to be correctly placed in the stream, and has been shown to

drastically increase conversation quality[50]. The sequencing feature of RTP allows

this to be accomplished.

In addition to sequencing RTP also provides other valuable media-specific features. It

has a built-in field to represent the codec used according to a defined list of standard

codecs that is kept by the IANA[30]. It also provides a timestamp when the packet is

created (used by RTCP, see below), and a marker bit, which is usually used to signal

the start of a new audio stream, or a special type of packet.

RTP runs together with RTCP (Real-Time Control Protocol). RTCP is a protocol in

which the two endpoints communicate things like delay, packet loss, and jitter to each

other over the network. Some applications may use RTCP to renegotiate a media

32

connection depending on the integrity of the channel. For example, if bandwidth

seems to be creating excessive delays and packet losses, a new codec can be used that

represents a lower voice quality, but requires less bandwidth.

33

5

VoIP and Security

This section discusses the role of security in VoIP systems. Section 5.1 provides

an overview of Internet security in the context of VoIP systems. Following that,

Section 5.2 moves onto issues specific to VoIP systems. Since the main focus of this

thesis is the effect of security on conversation quality, this section is only a brief

summary of Internet security and how it applies to VoIP. The reader is referred to

the references for more information on the topic of Internet security.

5.1

Internet Security Overview

In the early development of the Internet, security was hardly in anyone's thoughts.

The Internet at that stage was the ARPANET, which was a network of computers on

which everyone knew everyone else who was connected. Thus, the need for security

was overlooked; at that time the entire ARPANET was basically a private network[28].

However, as the ARPANET evolved into the public Internet, the need for security

became recognized. As a result security usually became a layer that ran over the

existing non-secure protocols, such as TCP and UDP. This Section first discusses

exactly what is meant by Internet security, and then moves on to the details of how

security is generally accomplished today.

5.1.1

Definition of Security

In general, Internet security can be divided into four central issues. These issues are:

confidentiality (privacy), integrity, availability, and non-repudiation.

Confidentiality or Privacy

Confidentiality means keeping your information private. Confidentiality can be extremely important for military, business, or personal reasons. A user should be able

to control who has access to information he wants to keep private. Confidentiality

in the context of VoIP means that a person who isn't involved in the conversation

should not be able to determine who is talking to whom, or what is being said.

Integrity

Integrity implies that information has not been modified or concealed. It also means

that the source of information cannot be changed. Integrity basically means that

whatever information you receive is guaranteed to be what you think it is. A malicious

attacker cannot modify the information without you knowing, and can't pretend to be

someone he is not. Integrity in VoIP systems implies that the person you are talking

to is who they claim to be, and their words cannot be altered in transit. Integrity

is also important in communicating with VoIP servers that may route or track your

34

calls.

A second, more subtle aspect of integrity is that the conversation should not be able

to be replayed at some date as though it is live. This aspect is known as replay

protection.

Availability

Availability means that an attacker should not be able to prevent a person from using

a system. A compromise of availability is usually accomplished through a denial of

service (DoS) attack. DoS attacks can be specifically targeted at a single point or can

take down an entire system. For VoIP systems to maintain availability it should be

impossible for attackers to prevent a single person from using VoIP. A less stringent

definition of availability implies that attackers should not be able to take down crucial

components of the VoIP architecture (e.g. SIP Servers).

Defending availability is the most difficult security task to accomplish because of the

large number, distributed location, and shared functionality of the network devices

that participate in a single call. Additionally, any denial of service attack on the

Internet could potentially affect VoIP users. One example of such an attack occurred

in 2001, when the "Code Red" worm took down significant portions of the Internet for

extended periods of time, costing industry and government an estimated $2.6 billion

in damages[12].

Non-Repudiation

Non-repudiation means preventing the sender of a message from denying it was transmitted by them. Non-repudiation prevents a user who promised something from

denying he made the promise. In the context of VoIP, non-repudiation means that a

person shouldn't be able to deny making a call he has made; there should be some

proof that would contradict this claim.

5.1.2

Security Details

The four elements of security are accomplished through various mechanisms. Two

important mechanisms are authentication and encryption. Both of these mechanisms

rely on the use of secret keys, which are usually large numbers known only to a

particular user or group of users. A password is another common type of secret key.

In this section, we are not discussing the mathematics of security per se, but more

the general principles involved with shared secret and public key cryptography. Then

we will discuss authentication and encryption in the context of these mechanisms.

Finally, we'll go over a few specific implementations of security. This section is not

meant to be a comprehensive guide to Internet Security, but merely a review to

provide enough information necessary to understand security in the context of this

thesis. Reference [24] is an excellent source of comprehensive information about

35

cryptography systems.

Shared Secret vs. Public Key

As mentioned previously, there are two main cryptographic mechanisms, shared-secret

and public key. Both of these mechanisms rely on the use of large, "secret" numbers,

but they differ slightly in how they work.

In shared-secret, or symmetric systems, all parties must know the value of the key.

The key becomes the "shared secret", and anyone who knows the key is assumed

to be a trusted party. One of the challenges that faces shared-secret systems is key

distribution. Everyone must be able to determine the value of the secret key, but

this must be done in a way that prevents non-trusted parties from also learning the

secret. Because of this, shared keys have to be placed manually in systems.

In contrast, public key schemes, originally developed by Ron Rivest of MIT, use a

single secret per user, along with a "public key" for that user that is viewable by

anyone[26]. This prevents the need for key-exchange, but does represent a problem,

as a database or record of all public-keys must be maintained.

Another problem with public key encryption is that is computationally more expensive than shared secret encryption. Many applications get around this problem by

using public key encryption to authenticate a Diffie-Hellman key exchange. DiffieHellman key exchange[25] was introduced in 1976 as a way to use two private individual keys to arrive at a single shared secret. Diffie-Hellman key exchange, on its own,

does not provide authentication, but by combining Diffie-Hellman with public-key

authentication, a shared secret can be securely negotiated. This negotiated key, can

then be used for the remainder of the communication, allowing it to be more efficient.

To more closely understand the difference between these two mechanisms, we will

look at them in the context of authentication and encryption schemes.

Authentication

Authentication is a technique that allows a user to ensure that certain messages are

authentic. Authentication can be used to provide both integrity and non-repudiation

of data. In addition, password protecting access to certain files can ensure their confidentiality, although if the files are transmitted over the Internet additional measures

must also be taken.

One method of authentication is digital signatures. Digital signatures use a mathematical function that is dependent on both the data being sent and the secret key

of the sender. This function is called a one-way function or hash function, and has

the special property that it is easy to compute in one direction, but computationally

infeasible to compute the other way.

In a shared-secret system, when a piece of data is transmitted, the hash function is

used with a key to generate a digital signature that is attached to the data. The

36

receiver of the data can then compute the signature if he knows the key, and verify

that it matches. This makes it nearly impossible for a malicious attacker to change

the message, because it would change the signature in an unpredictable way. Of

course, if the attacker knew the key it would be possible to create a new message and

signature pair, but most security systems rely on the assumption that the key is not

known.

In a public key system, authentication works much the same way. The signature is

only creatable by the private key, known only to the signer. Anyone, however, can

use his public key, with a different mathematical function, to verify that the signature

was created with the original data and private key.

Authentication proves that the message has not been tampered with and that the

sender of the message knew the key. This ensures that the data's integrity is intact. By

authenticating a sequence number replay attacks can also be prevented. Additionally,

in a public-key system, the sender cannot deny sending the message, ensuring nonrepudiation. There is, however, no non-repudiation for a shared key system, as any

party involved in the communication is capable of sending and receiving all messages

with the single key.

There are various algorithms used to compute hash functions. Two of the more common ones are MD5, which was developed by MIT Professor Ron Rivest[61] and SHAl

(Secure Hash Algorithm, Version 1) [62], which was part of the U.S. Government's

Capstone project[63], a project that attempted to develop a set of cryptographic

standards.

Encryption

Encryption is the technique that is commonly used to provide confidentiality, particularly when data is in transit over a non-trusted network, such as the Internet. Typical

encryption mechanisms use a one-way cryptographic function to convert readable data

into seemingly random values, again using a secret key. In a shared-secret system, the

data can then only be decrypted by anyone who knows the secret key using another

function. In public key systems, data can be encrypted with the public key, and only

someone who knows the secret key is able to decrypt it. By encrypting information

before sending it over a network and decrypting it on the receiving side, the data is

kept private from anyone on the network who doesn't know the key, thus ensuring

confidentiality.

There are also various encryption algorithms employed in different areas. In 2000,

the National Institute of Standards (NIST) held a competition to determine the

new encryption standard. Ultimately an algorithm known as Rijndael became the

Advanced Encryption Standard (AES, as it is also now known), beating out other

algorithms including Ron Rivest's RC6, MARS, Twofish, and Serpent[52]. Still, AES

is not the only encryption algorithm used, and the older 3DES and RC5 are also

widely employed.

37

5.1.3

Security Implementation