Changes in Agricultural Markets in Transition Economies.

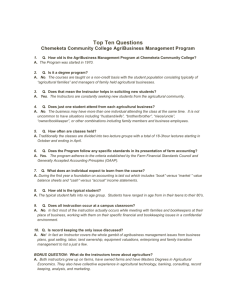

advertisement