THE RESTORATIVE ECONOMY Following Jesus where the need is greatest

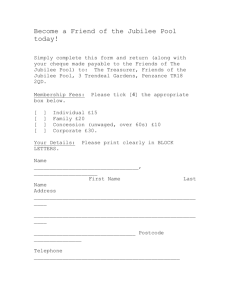

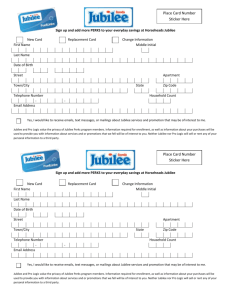

advertisement