The Recreation Opportunity Spectrum: A Framework for Planning, Management, and

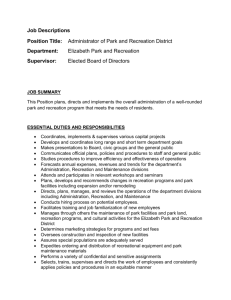

advertisement