Economic Assessment of Using a Mobile Micromill for Processing Small- ®

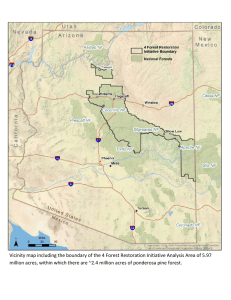

advertisement