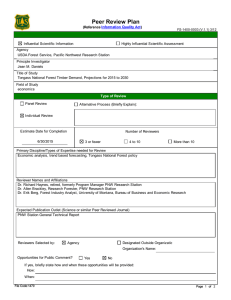

Alaska’s Timber Harvest and Forest Products Industry, 2011

advertisement