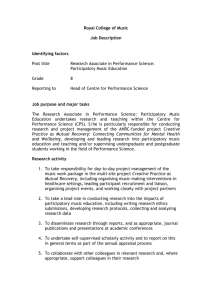

Challenges for participatory development in contemporary

advertisement