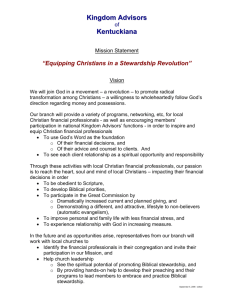

The mission of the church and the role of advocacy

advertisement