Examining the Generalizability of Problem-Solving Appraisal in Black South Africans

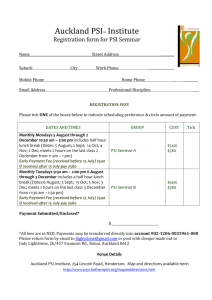

advertisement