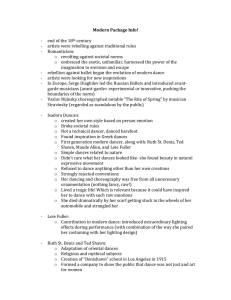

Dancing on the Horizon Laura Knott Bachelor of Arts 1987

advertisement