by 1980 Diploma in Architecture, School of Architecture,

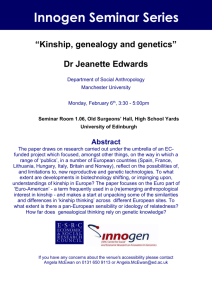

advertisement