OL1NTIAL AGEIC Ui2URAL RSOURCS by AkB NAKAJUD OOLLGi

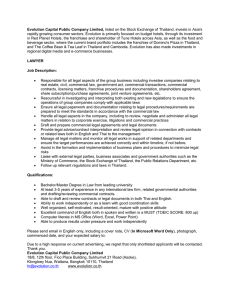

advertisement