- JOHN DOE The United States Social Security Retirement Benefit:

advertisement

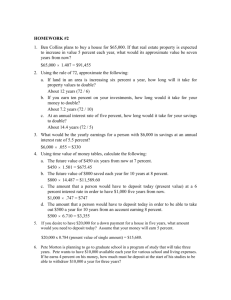

- The United States Social Security Retirement Benefit: Are We Getting Our Money's-Worth? . HAS BEEN ESTABLISHED fOR JOHN DOE SIGNATURE FOR SOCIAL SECURITY AND TAX PURPOSES-NOT fOR IDENTIFICATION An Honors Thesis (Honrs 499) - By Jeffrey J. Lane Ball State University Muncie, Indiana April, 1995 Expected Date Of Graduation: May 6, 1995 Sf Coil -11'1'( I'" !T '- • .1 - .1 Table Of Contents I'I I i c."~.~ Acknowledgements i Introduction 1 A Brief Overview Of The U.S. Social Security System 2 Necessary Assumptions 3 The Basic Procedure . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8 Tables: - . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. 11 Interest Rates . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .. 11 Annual Wages & Tax Amounts 12 Monthly Benefit Awards . . . . . 14 Life Expectancies At Retirement 15 Accumulated Tax Values . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16 Value Of Future Benefits . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17 Benefit/Tax Return Ratios 19 Conclusions . . - I References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 Interpretation Of Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25 - i Acknowledgements I I would like to thank Dr. John Beekman for his constant advice and support throughout the semester. His knowledge, enthusiasm, and willingness to help are a great asset to Ball State University. I would also like to thank the Honors College for giving me the opportunity to research a timely and relevant topic in the actuarial field. This project has been a good experience and can only help me in my future endeavors . .I - I I. Introduction Many Americans ask: Will I really get my money's-worth out of the U.S. Social Security system? People are curious as to whether or not they will get a full return on the dollars they have put into the program in the fo~ of payroll taxes. If one was to try and answer this question based only on stories that have made headlines as of late, undoubtedly the answer would be a resounding "no". In fact, if a person was to rely strictly on what the media has said about the condition of the Social Security program, they would feel lucky to get any return at all on their investment. The media, however, with its usual tendency to exaggerate a newsworthy story, paints a darker picture of the financial strength of the Social Security system than it should. The fact is, the majority of workers who retired in the past have received far more in benefits than they have payed in taxes. Single, average wage-earning men who retired in 1960, received nearly a 1500 percent return on the taxes they had payed! Clearly, this was an impossible situation that could not continue. Worker's returns on investment have been steadily decreasing ever since the unrealistic dividends of the 60's, with the benefit/tax ratios figuring to level out at about 160 percent for single average wage-earning males retiring in 2010 and later. - 2 ! II. A Brief Overview Of The U.S. Social Security System Social insurance is a byproduct of the Industrial Revolution of the 1700's and early 1800's. During that time, a great number of people migrated from rural areas to go to work in the cities. Most of these workers' wages were far too low to allow them to save for old-age, and disability or unemployment usually meant the financial devastation of a family. Our United States was one of the last major industrialized nations to implement a social security program. Only in 1935, after American workers had felt first hand the economic effects of the Great Depression, was Congress impelled to pass the Social Security Act. In the program's infancy, it provided cash benefits only to retiring workers in commerce and industry. Then in 1939, the act was amended to include wives and dependent children of retired workers and the widows and dependent children of deceased workers [5, p.557]. Today, over 91 percent of all workers in the United States are covered by Social Security [1, p.1]. The few exceptions are federal employees hired before 1984, who are generally covered by Civil Service Retirement, railroad workers covered by the Railroad Retirement System, and about 20 percent of the state and local government employees [2, p.5]. Social Security pays benefits to a worker and his/her family when he/she retires, - dies, or becomes disabled provided that all eligibility I requirements are met. These benefits are paid for through - 3 i payroll taxes. The total tax is split evenly between the employer and the employee. In 1993 41 million people were receiving Social Security benefits, while 134 million were paying into the system [2, p.2]. III. Necessary Assumptions Posing the question of whether or not individuals get their money's-worth from the Social Security taxes they pay is much easier to do than it is to answer that same question. There are almost an infinite number of variables and intangibles that make their way into the equation that might provide us an answer. Therefore, it is impossible to come up with a precise or definitive answer to this question. Any type of analysis must employ certain assumptions, and then employing these assumptions, approximate benefit/tax ratios can be calculated and used to make pertinent comparisons among the different classifications of workers. When nonactuaries tackle this type of problem, the resulting figures are often misleading. Nonactuaries may have poor methodology or may simply use inconsistent assumptions such as the use of interest rates that are too high when compared to assumed earnings growth. The key to accurate analysis lies in the use of assumptions - that are both consistent and realistic. i One of the most important factors in the final analysis of the problem, is - I 4 whether the benefit/tax ratios should be calculated using only payroll taxes payed by the employee himself or the combined employer-employee payroll taxes. Some would say that using the combined payroll tax would be more accurate because the employee ultimately pays for the employer's portion through lower wages. This may not be the case, however, when considered on an individual basis. Other people contend that the employer's portion is passed on to the consumer (who, in general, is either an employee or his/her family). However, one cannot determine whether or not the employees do in reality absorb this tax. For my analysis, only the employee payroll tax will be considered. Changing to the combined employer-employee tax consideration can be accomplished by simply halving all benefit/tax ratios. In all actuality, the real portion of the payroll tax to be considered would fall somewhere between these two points of view. Where exactly it would be, however, is anybody's guess and impossible to determine with any kind of accuracy. present another problem. payroll tax rates. Self-employed workers They pay the combined employer-employee They are also, however, allowed to deduct approximately 50 percent of these taxes on their tax returns [7, p.249]. In reality then, they are still only paying a rate roughly equal to that of the company employed worker. Another unavoidable problem that presents itself when attempting to evaluate the complex Social Security program, is how to take into account the entire benefit structure with regard to payroll taxes. The solution to this problem comes from Myers' and Schobel's "An Updated Money's-Worth Analysis of Social -- 5 I Security Retirement Benefits", "The failure to consider disability benefits, survivor benefits payable in the case of death before retirement age, and Hospital Insurance (HI) benefits can be mitigated to a considerable extent by taking into account only the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance (OASI) portion of the total payroll tax, which supports both the OASDI and the HI programs [7, p.249]." Therefore, for our purposes, only the retirement benefits will be considered. This allows for the simplification of the concepts and the calculations to be used. It also makes the analysis less technical and therefore, more easily understood by the general population. Because this analysis is based on the "generic" tax-payer - and worker, another assumption must be made concerning the value of benefits to those workers who die prior to attaining retirement age. However, because very few workers actually do die before reaching retirement age, the benefits paid out to their survivors have a relatively small impact on this analysis, so we will assume that no one dies before attaining retirement age [7, p.250]. Without this assumption there is no methodology that can simply be applied to this money's-worth analysis problem. The analysis would become too technical for nonactuaries to easily interpret, and the net effect of including the preretirement death benefits would be very minimal. Yet another problem which must be considered when attempting to accumulate the preretirement taxes paid and discount the - postretirement benefits is finding an appropriate interest rate. For the purposes of accumulating the preretirement taxes paid, - 6 I the nominal interest rates, compounded annually, will be used. A nominal interest rate of 2.3 percent will be assumed for the years 1937-1950 because the actual rates are difficult to calculate [6, p.535]. For the period from 1951-1992, however, the actual nominal rates are available, as are projected future rates (1993 and after) calculated under the intermediate assumptions of the 1993 OASDI Trustees Report. Calculating the present value of the postretirement benefits, however, will involve using an approximated "real" interest rate. The real interest rate is equivalent to the difference between the nominal interest rate (what most people think of when they think of "the interest rate") and annual increases in the Consumer Price Index (CPI). For example, if the CPI were four percent and the nominal rate 7.1 percent, the "real" interest rate would be 3.1 percent. For simplification purposes, a real interest rate, that when compounded monthly is equivalent to an annual rate of two percent will be used. This will be assumed and applied to the past, the present, and the future. The actual real interest rates did and will fluctuate above and below the two percent level, but two percent is generally accepted as a good approximation of the real interest rates [7, p. 251]. By using a reasonable approximation of the future real rates from the 1993 OASDI Trustees Report, postretirement benefit increases will automatically be taken into account, solving two problems at once. Other necessary assumptions must also be used as we make a "general" analysis of the benefit/tax ratio. All hypothetical workers are assumed to be steadily employed in a Social Security - 7 ! contributing job from age 21 through 65 excluding, of course, periods of unemployment. Unemployment would tend to reduce the amount of taxes paid, but would not necessarily reduce the benefits received. It would, however, be impossible to generalize its effect on the benefit/tax ratios with any certainty. All average earning and maximum earning workers, as defined by the intermediate assumptions of the 1993 OASDI Trustees Report, are also assumed to remain in the category of average earning or maximum earning over all years of their employment. These earning patterns are far from typical, but must be assumed in order to analyze the aforementioned "generic" worker. In reality, most workers tend to earn less than average at the beginning of their employment, are earning above average by the middle, and then decline again in their later years. Most maximum earning workers also earn less than the maximum in early years, usually reaching the maximum level for OASDI taxation around age 30 [6, p.537]. The net effect of these more typical earning patterns, however, is relatively small, and will therefore be ignored [7, p.256]. Our final assumptions also deal with the hypothetical worker being considered in this analYSis. It will be assumed that all workers retire at the Normal Retirement Age (NRA). This assumption is true for the most part and any effects from those workers retiring early are usually balanced by those retiring late. - It will also be necessary to assume in the case of married couples, that each individual will receive benefits based on their own earnings record. This generally the case now and will 8 be even more valid in the future. Therefore, no figures will be included for married couples and benefit/tax ratios will be calculated for the individual only, for both males and females. IV. The Basic Procedure This brings us to an explanation of the basic procedure to be used in calculating these benefit/tax ratios that we are so interested in. In order to compare the benefits received to the taxes that have been payed in, both amounts must be brought together to a common point in time. For the purposes of this paper, this point in time will be the date of retirement. - Therefore, we must accumulate the OASI taxes with interest to the retirement age and compare this to the present value of the future benefits to be received as of that same time. The present value of these future benefits would, of course, be different for each individual depending both on mortality and, as a result of the changes in the normal retirement age which are currently being implemented, the year of retirement. must come into our equation. Another assumption It will be assumed that all individuals retiring at the normal retirement age will live exactly as long as they are expected to. That is, their life expectancy will be based on the patterns of an age-specific mortality table, taking into consideration the decreases in - mortality rates that both have occurred and are expected to I 9 --I occur. Thus, we are allowing for the increased life spans of individuals in the future. The basic formula used for calculating the present value of the worker's future monthly benefits at the time of retirement is (Table VI) : [4, p. 59]. PV = PMT*aii i where 'n' is the number of monthly payments the worker could expect to receive and 'i' is the monthly interest rate equivalent to an annual rate of two percent. Using the infor.mation from the average wage-earning male retiring in 1960: PV = A $107.00*a-155 .16516 = $14,621.67 similar formula can be used to calculate the value of the accumulated taxes at the time of retirement (Table V) : [4, p. 60]. Again, using the infor.mation from the average wage-earning male - retiring in 1960: 1 10 FV = $11.50*(1.023)*(1.023)* ... *(1.026) + $10.53*(1.023)* (1.023)* ... *(1.026) + ... + $73.48*(1.026) + $86.76 = $976.21 This fo~ula is somewhat more complex because we can no longer use the constant interest rate assumption, and because the values we are accumulating vary from year to year. 11 - Table I Year - - I I 1937 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 Nominal Rate 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.3 2.3 2.5 2.5 2.6 2.6 2.9 3.8 3.9 3.9 4.1 4.2 4.9 5.0 5.5 6.6 7.3 6.0 5.9 6.6 7.5 7.4 CPI 3 3.6 -1.9 -1.4 1.0 5.0 10.7 6.1 1.7 2.3 8.5 14.4 7.8 -1.0 1.0 7.9 2.2 0.8 0.5 -0.4 1.5 3.6 2.7 0.8 1.6 1.0 1.2 1.2 1.3 1.6 3.0 2.8 4.2 5.4 5.9 4.3 3.3 6.2 11.0 9.1 '" I: Real Rate -1.3 4.2 3.7 1.3 -2.7 -8.4 -3.8 0.6 0.0 -6.2 -12.1 -5.5 3.3 1.3 -5.7 0.1 1.6 1.8 2.7 1.0 -1.1 -0.1 1.8 1.3 2.8 2.7 2.7 2.8 2.6 1.9 2.2 1.3 1.2 1.4 1.7 2.6 0.4 -3.5 -1.7 (1): Nominal rates 1937-1974 [7, pp. 254-255]. (2): CPI 1937-1974 [1, p. 57]. (3): Nominal rates and CPI 1975-2070 [10. p. 59]. Interest Rates Year Nominal Rate CPI Real Rate 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 2055 2060 2065 2070 7.1 7.1 8.2 9.1 11.0 13.3 12.8 11.0 12.4 10.8 8.0 8.4 8.8 8.7 8.6 8.0 7.1 6.3 5.9 5.9 6.0 6.0 6.1 6.3 6.4 6.3 6.3 6.3 6.3 6.3 6.3 6.3 6.3 6.3 6.3 6.3 6.3 6.3 6.3 5.7 6.5 7.7 11.4 13.4 10.3 6.0 3.0 3.5 3.5 1.6 3.6 4.0 4.8 5.2 4.0 2.9 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.5 3.7 3.9 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 4.0 1.4 0.6 0.5 -2.3 -2.4 3.0 6.8 8.0 8.9 7.3 6.4 4.8 4.8 3.9 3.4 4.0 4.2 3.3 2.8 2.7 2.7 2.5 2.4 2.4 2.4 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 2.3 Alternative II assumptions. , 12 - - I Table IIA: Year 1937 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 Annual Wages & Tax Amounts Average Earner's Maximum Earner's OASI Wage Tax Rate Taxes Taxes Waae 1.000% $1,150.45 $11.50 $3,000.00 $30.00 3,000.00 1.000 1,053.23 10.53 30.00 1.000 1,142.35 11.42 3,000.00 30.00 1,195.01 3,000.00 30.00 1.000 11.95 1,276.03 12.76 3,000.00 30.00 1.000 1.000 1,454.27 14.54 3,000.00 30.00 1.000 1,713.52 17.14 3,000.00 30.00 1.000 1,936.32 19.36 3,000.00 30.00 2,021.39 1.000 20.21 3,000.00 30.00 1.000 1,891.76 18.92 3,000.00 30.00 1.000 2,175.32 21.75 3,000.00 30.00 1.000 2,361.66 23.62 3,000.00 30.00 1.000 2,483.19 3,000.00 24.83 30.00 2,543.95 38.16 3,000.00 45.00 1.500 1.500 2,799.16 41.99 3,600.00 54.00 1.500 2,973.32 44.60 3,600.00 54.00 3,600.00 1.500 3,139.44 47.09 54.00 2.000 3,155.64 63.11 3,600.00 72.00 2.000 3,301.44 66.03 4,200.00 84.00 3,532.36 2.000 70.65 4,200.00 84.00 3,641.72 2.000 4,200.00 72.83 84.00 2.000 3,673.80 73.48 4,200.00 84.00 2.250 3,855.80 86.76 4,800.00 108.00 2.750 4,007.12 110.20 4,800.00 132.00 4,086.76 2.750 112.39 4,800.00 132.00 4,291.40 2.875 123.38 4,800.00 138.00 3.375 4,396.64 148.39 4,800.00 162.00 3.375 4,576.32 154.45 4,800.00 162.00 3.375 4,658.72 157.23 4,800.00 162.00 3.500 4,938.36 172.84 6,600.00 231.00 3.550 5,213.44 185.08 6,600.00 234.30 3.325 5,571.76 185.26 7,800.00 259.35 3.725 5,893.76 219.54 7,800.00 290.55 3.650 6,186.24 225.80 7,800.00 284.70 4.050 6,497.08 263.13 7,800.00 315.90 4.050 7,133.80 288.92 9,000.00 364.50 4.300 7,580.16 325.95 10,800.00 464.40 4.375 8,030.76 351.35 13,200.00 577.50 4.375 8,630.92 377.60 14,100.00 616.88 (1): Tax rates, wages, and tax amounts 1937-1975 [6. p. 538]. 13 - Table lIB: ! Year 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 2055 2060 2065 2070 - - I Annual Wages & Tax Amounts Average Earner's OASI Wage Taxes Tax Rate 9,226.48 403.66 4.375 9,779.44 427.85 4.375 4.275 10,556.03 451.27 497.06 4.330 11,479.46 12,513.46 565.61 4.520 13,773.10 647.34 4.700 4.575 14,531.34 664.81 727.67 4.775 15,239.24 16,135.07 839.02 5.200 16,822.51 874.77 5.200 5.200 17,321.82 900.73 958.18 5.200 18,426.51 5.530 19,334.04 1069.17 20,099.55 1111.51 5.530 21,027.98 1177.57 5.600 5.600 21,811.60 1221.45 5.600 22,935.42 1284.38 24,143.42 1352.03 5.600 5.600 25,384.98 1421.56 5.600 26,737.74 1497.31 5.600 28,141.28 1575.91 5.600 29,613.54 1658.36 5.600 31,147.78 1744.28 5.600 32,765.11 1834.85 5.490 34,464.16 1892.08 5.490 44,195.83 2426.35 5.490 56,675.43 3111.48 5.490 72,678.92 3990.07 5.490 93,201.31 5116.75 5.490 119,518.63 6561.57 5.490 153,267.18 8414.37 5.490 196,545.34 10790.34 5.490 252,043.98 13837.21 5.490 323,213.81 17744.44 5.490 414,479.91 22754.95 5.490 531,516.89 29180.28 5.490 681,601.67 37419.93 5.490 874,066.00 47986.22 5.490 1,120,876.61 61536.13 Maximum Earner's Wage Taxes 669.38 15,300.00 16,500.00 721.88 17,700.00 756.68 22,900.00 991.57 25,900.00 1170.68 29,700.00 1395.90 32,400.00 1482.30 35,700.00 1704.68 37,800.00 1965.60 39,600.00 2059.20 42,000.00 2184.00 2277.60 43,800.00 45,000.00 2488.50 48,000.00 2654.40 51,300.00 2872.80 53,400.00 2990.40 55,500.00 3108.00 57,600.00 3225.60 60,600.00 3393.60 64,200.00 3595.20 67,500.00 3780.00 71,100.00 3981.60 74,700.00 4183.20 78,600.00 4401.60 82,800.00 4545.72 106,200.00 5830.38 136,200.00 7477.38 174,600.00 9585.54 223,800.00 12286.62 286,800.00 15745.32 368,100.00 20208.69 472,000.00 25912.80 605,300.00 33230.97 776,200.00 42613.38 995,400.00 54647.46 1,276,500.00 70079.85 1,636,900.00 89865.81 2,099,200.00 115246.08 2,691,900.00 147785.31 I (1): Tax rates, wages, and tax amoWlts 1976-2070 [7, pp. 255-256]. 14 - I Table III: Year Of Retirement 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 - (1): (2): (3): (4): - Average Benefit 107.00 108.40 111.40 114.40 117.50 120.00 120.60 122.00 141.30 143.60 168.40 189.00 232.10 237.90 254.00 271.00 292.30 315.90 342.20 400.30 450.90 532.80 535.40 553.00 542.80 548.40 576.40 593.50 Monthly Benefit Awards Maximum Benefit 3 119.00 120.00 121.00 122.00 123.00 131.70 132.70 135.90 156.00 160.50 189.80 213.10 216.10 266.10 274.60 316.30 364.00 412.70 459.80 503.40 572.00 677.00 979.30 709.50 703.60 717.20 760.10 789.20 Average Benefit Year Of Retirement 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 2055 2060 2065 2070 626.50 668.50 720.40 751.10 794.90 820.20 829.50 867.30 905.50 945.30 986.90 1,030.30 1,075.60 1,386.50 1,824.10 2,339.80 3,020.80 4,029.40 5,167.20 6,627.00 8,498.30 10,898.30 13,975.40 17,922.60 22,983.40 29,473.90 37,796.60 Average earner's benefits 1960-1978 [6, p. 542]. Maximum earner's benefits 1960-1994 [8, p. 63]. Average earner's benefits 1979-1994 [3]. Average and maximum earner's benefits 1995-2070 [10, Alternative II assumptions. p. 189]. Maximum Benefit 4 838.60 899.60 975.00 1,022.90 1,088.70 1,128.80 1,147.50 1,210.30 1,273.70 1,340.30 1,410.50 1,484.30 1,562.20 2,088.00 2,835.40 3,698.30 4,787.50 6,376.20 8,176.10 10,477.80 13,415.60 17,193.20 22,052.30 28,287.90 36,283.60 46,536.60 59,682.30 15 - I Table IV: Year Of Retirement - 1937 1938 1939 1940 1941 1942 1943 1944 1945 1946 1947 1948 1949 1950 1951 1952 1953 1954 1955 1956 1957 1958 1959 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 I Life Expectancies At Retirement NRA Life Expectancy Female Male 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 11.8 12.1 12.0 11.9 12.2 12.4 12.1 12.5 12.6 12.9 12.6 12.7 12.8 12.8 12.8 13.0 12.9 13.2 13.1 13.0 12.9 12.9 13.1 12.9 13.1 12.9 12.7 13.0 12.9 12.9 13.0 12.8 13.0 13.1 13.1 13.1 13.2 13.5 13.7 (1): Life expectancies 1937-2070 [9, 13.1 13.4 13.4 13.4 13.8 14.1 13.7 14.1 14.4 14.6 14.5 14.7 14.9 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.3 15.7 15.6 15.7 15.6 15.7 15.9 15.9 16.1 16.0 16.0 16.3 16.3 16.3 16.6 16.6 16.9 17.1 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.7 18.0 p. 16]. Year Of Retirement NRA Life Expectancy Male Female 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 2055 2060 2065 2070 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:0 65:6 66:0 66:0 66:2 67:0 67:0 67:0 67:0 67:0 67:0 67:0 67:0 67:0 67:0 13.7 13.9 13.9 14.2 14.0 14.2 14.5 14.3 14.4 14.4 14.5 14.6 14.6 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.4 15.5 15.5 15.6 15.7 15.7 15.8 15.8 15.9 15.6 15.3 15.5 15.5 14.9 15.1 15.3 15.5 15.7 15.9 16.1 16.3 16.5 16.7 Alternative II assumptions. i 18.1 18.3 18.3 18.6 18.4 18.6 18.8 18.6 18.7 18.6 18.7 18.7 18.7 18.9 19.0 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.2 19.3 19.4 19.4 19.5 19.5 19.6 19.3 19.0 19.2 19.2 18.7 18.9 19.1 19.3 19.5 19.7 20.0 20.2 20.4 20.6 i 16 - Table V: I Accumulated Tax Values Year Of Retirement Accumulated Taxes Average Maximum Year Of Retirement 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 $976.21 $1,364.05 1,535.60 1,114.72 1,725.96 1,269.46 1,931.27 1,422.35 1,646.99 2,168.59 1,868.96 2,419.50 2,683.12 2,104.69 3,045.59 2,380.66 2,684.77 3,432.17 3,880.29 3,017.70 3,436.41 4,426.94 5,034.81 3,913.06 4,410.98 5,652.79 4,960.15 6,350.81 5,613.46 7,234.36 6,385.82 8,354.44 7,235.97 9,589.54 8,153.38 10,939.78 9,160.13 12,438.38 10,362.53 14,215.00 11,802.58 16,500.13 13,666.47 19,485.83 16,056.54 23,277.94 18,700.95 27,524.37 21,396.71 32,022.95 24,786.61 37,702.54 28,220.00 43,555.42 31,235.97 48,930.16 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 2055 2060 2065 2070 Accumulated Taxes Average Maximum 34,640.21 38,544.09 42,771.97 47,392.49 52,119.54 56,779.57 61,353.80 65,830.64 70,568.24 75,669.74 81,093.89 86,708.50 92,835.82 129,907.65 175,883.88 231,635.73 298,977.80 387,743.95 488,164.91 619,216.34 792,457.78 1,014,657.64 1,300,439.34 1,667,645.37 2,138,539.30 2,742,400.01 3,516,773.28 55,006.68 62,004.78 69,701.91 78,195.72 87,047.63 95,923.36 104,763.35 113,672.19 123,146.15 133,457.09 144,558.12 156,331.40 169,093.23 248,587.31 356,431.36 496,679.62 679,302.84 915,553.32 1,170,584.49 1,488,230.86 1,902,992.56 2,437,208.42 3,123,477.66 4,005,110.11 5,135,760.30 6,585,332.95 8,444,930.06 17 ~ I - - Table VIA: Year Of Retirement 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 Value Of Future Benefits At Time Of Retirement Average Earning Male Female $14,621.67 $17,515.04 17,980.71 15,063.96 18,316.44 15,222.94 18,809.70 15,455.58 16,147.34 19,660.36 20,078.67 16,398.13 20,179.06 16,480.13 16,765.75 20,765.00 24,049.95 19,199.39 19,734.11 24,750.10 23,401.94 29,384.69 26,264.65 32,979.26 32,254.10 40,664.86 33,243.10 41,849.83 36,077.05 45,578.60 39,111.89 49,199.31 42,186.00 53,474.56 46,072.06 58,231.86 49,907.75 63,079.90 59,591.79 74,898.97 66,102.70 83,430.37 79,316.77 99,690.67 80,911.12 100,915.21 82,740.25 103,470.23 81,622.11 101,936.18 82,464.20 102,609.54 87,107.16 108,246.16 90,579.89 111,457.48 Maximum Earning Male Female $16,261.48 $19,479.35 16,675.97 19,904.85 16,534.79 19,894.87 16,482.35 20,059.29 20,580.63 16,903.17 22,036.34 17,996.95 18,133.60 22,203.66 18,675.94 23,130.85 21,196.78 26,551.97 22,056.58 27,662.89 26,375.82 33,118.85 29,613.74 37,184.55 30,030.64 37,861.60 37,183.64 46,810.59 39,002.99 49,275.13 45,649.78 57,423.40 52,534.05 66,591.66 60,189.74 76,075.61 67,058.99 84,757.86 74,940.06 94,189.72 83,856.17 105,837.59 100,783.51 126,671.51 147,994.51 184,583.98 106,155.89 132,752.49 105,801.99 132,133.93 107,847.05 134,193.22 114,868.41 142,744.45 120,447.59 148,209.35 18 .--., -- - Table VIB: Year Of Retirement 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 2055 2060 2065 2070 Value Of Future Benefits At Time Of Retirement Average Male $95,616.34 105,503.32 114,225.97 119,647.23 126,624.39 131,257.99 132,746.29 140,068.46 146,900.62 153,357.43 160,827.54 167,900.11 176,067.11 223,918.97 289,227.64 374,442.15 483,423.74 623,977.83 811,672.19 1,050,771.10 1,359,997.30 1,768,047.50 2,287,661.10 2,972,888.40 3,845,633.50 4,974,190.50 6,460,293.70 Earning Female $117,654.78 126,462.28 136,774.88 142,603.57 152,008.00 157,406.33 159,191.11 167,036.81 175,010.35 182,702.69 191,413.69 199,831.31 210,075.93 267,031.63 346,322.95 449,035.99 579,728.15 756,708.99 977,495.75 1,267,275.20 1,636,721.90 2,113,774.20 2,738,993.50 3,548,836.30 4,597,168.70 5,934,783.20 7,686,050.60 Maximum Earning Male Female $127,987.01 $157,486.51 141,975.74 170,180.21 154,595.12 185,113.14 162,943.88 194,207.41 173,425.56 208,191.11 180,643.77 216,630.41 183,636.37 220,219.17 195,462.77 233,096.56 206,634.26 246,174.15 217,438.88 259,046.25 229,858.39 273,572.81 241,885.01 287,886.65 255,719.63 305,114.00 337,210.83 402,136.35 449,578.46 538,327.99 591,845.21 709,748.62 766,151.73 918,779.31 987,394.51 1,197,430.80 1,284,315.10 1,546,699.00 1,661,350.50 2,003,660.10 2,146,921.20 2,583,764.60 2,789,278.60 3,334,698.40 3,609,785.00 4,321,959.00 4,692,219.30 5,601,259.10 6,071,052.50 7,257,491.50 7,853,793.20 9,370,481.50 10,201,055.00 12,136,572.00 19 - . I Table VIlA: Year Of Retirement - - 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 Benefit/Tax Return Ratios BenefitlTax Return Ratios For: Average Male 1497.80% 1351.37 1199.17 1086.62 980.42 877.39 783.02 704.25 715.12 653.95 681.00 671.20 731.22 670.20 642.69 612.48 583.00 565.07 544.84 575.07 560.07 580.38 503.91 442.44 381.47 332.70 308.67 289.99 Average Female 1794.19% 1613.02 1442.85 1322.44 1193.71 1074.32 958.77 872.24 895.79 820.16 855.10 842.80 921.90 843.72 811.95 770.45 739.01 714.21 688.64 722.79 706.88 729.45 628.50 553.29 476.41 413.97 383.58 356.82 Maximum Male 1192.15% 1085.96 958.01 853.45 779.45 743.83 675.84 613.21 617.59 568.43 595.80 588.18 531.25 585.49 539.14 546.41 547.83 550.19 539.13 527.19 508.22 517.21 635.77 385.68 330.39 286.05 263.73 246.16 Maximum Female 1428.05% 1296.23 1152.68 1038.66 949.03 910.78 827.53 759.49 773.62 712.91 748.12 738.55 669.79 737.08 681.13 687.34 694.42 695.40 681.42 662.61 641.43 650.07 792.96 482.31 412.62 355.93 327.73 302.90 20 - I Table VIIB: Year Of Retirement 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2005 2010 2015 2020 2025 2030 2035 2040 2045 2050 2055 2060 2065 2070 - Benefit/Tax Return Ratios BenefitlTax Return Ratios For: Average Male 276.03% 273.72 267.06 252.46 242.95 231.17 216.36 212.77 208.17 202.67 198.32 193.64 189.65 172.37 164.44 161.65 161.69 160.93 166.27 169.69 171.62 174.25 175.91 178.27 179.83 181.38 183.70 Average Female 339.65% 328.10 319.78 300.90 291.65 277.22 259.46 253.74 248.00 241.45 236.04 230.46 226.29 205.55 196.90 193.85 193.90 195.16 200.24 204.66 206.54 208.32 210.62 212.81 214.97 216.41 218.55 Maximum Male 232.68% 228.98 221.79 208.38 199.23 188.32 175.29 171.95 167.80 162.93 159.01 154.73 151.23 135.65 126.13 119.16 112.79 107.85 109.72 111.63 112.82 114.45 115.57 117.16 118.21 119.26 120.80 Maximum Female 286.30% 274.46 265.58 248.36 239.17 225.84 210.21 205.06 199.90 194.10 189.25 184.15 180.44 161.77 151.03 142.90 135.25 130.79 132.13 134.63 135.77 136.82 138.37 139.85 141.31 142.29 143.71 - 21 I V. Interpretation Of Results The most striking result of this money's-worth analysis has to be that all of the return ratios are above 100 percent. Thus, under the assumptions of this paper, each hypothetical worker will receive more in benefits than he/she payed in taxes. A few important points must be made here. First of all, no program can survive when it pays out more than it takes in. Again, the argument about whether or not to include the employer portion of the payroll tax could come into play. If this extra tax was to be considered, the resulting ratios would be one half of the ratios calculated in this paper and would cause many of the projected ratios to fall below the 100 percent level. Even with this consideration, the financial position of the program is in question. The pecuniary instability of the United states Social Security system has been widely publicized in recent years, and the OASDI Board of Trustees readily acknowledges this fact. In their words, "the OASDI program does not meet the requirements for the long-range test (over the next 75 years) of close actuarial balance. Individually, the OASI and DI Trust Funds also fail the long-range test. Because of this, appropriate options to strengthen the long-range financing of these funds should be developed [10, pp. 5,7]." The "appropriate options" that the Board of Trustees is speaking of to counteract - some of the financial problems include increasing taxes, decreasing benefits, and other possible changes, much like what was done in 1983. This, of course, would have a great impact on 22 ~- I the benefit/tax ratios that have been calculated. These new ratios would likely fall well below the 100 percent level if the necessary changes for financial stability were implemented, especially for those retiring beyond the year 2000. It must also be kept in mind that all of the benefit/tax return ratios calculated beyond 1993 are in some way affected by future projections. While the projections do attempt to account for "marriage and divorce rates, birth rates, death rates, migration rates, labor force participation and unemployment rates, disability incidence and termination rates, retirement age patterns, productivity gains, wage increases, cost-of-living increases, and many other economic and demographic circumstances - affecting the program [10, p. 13]", no one can see into the future. These are simply best estimates given the information available. The actual experiences will likely differ from the projections, and with them, the resulting return ratios. These points do not render the results of this paper useless, however. Some very important relationships and conclusions can be drawn from this money's-worth analysis. Some of the more obvious inferences from the study include the fact that women receive greater returns than men and average wageearning individuals receive greater returns than those making the maximum taxable amounts. A woman will, in general, receive a greater return on the taxes she has payed simply because of the fact that women generally live longer than their male - counterparts. The greater return realized by lower wage-earning workers, however, is an essential part of the United States - 23 I Social Security system. The program is designed in such a way as to weight the monthly benefit awards in favor of those with lower incomes, the workers for whom Social Security was originally designed. Two other interesting outcomes resulting from our money'sworth analysis include a dip in the return ratios after the year 2000 and the similarity between the return ratios for the average and maximum wage-earning individuals in the late 1970's. The slight decline in the return ratios after the year 2000 are a result of an increase in the normal retirement age. From 2000 to 2025 the normal retirement age is expected to increase from 65 to 67. - As a result, workers will pay more taxes over their working lifetimes and, at the same time, should expect to collect fewer monthly benefits. The connection between the average and maximum return ratios of the late 70's is a direct consequence of the small differences between the average and maximum wages from 1951-1971, the period during which a person retiring in the late 1970's would pay the majority of his/her taxes. Another important reason for doing a study such as this is that we can see exactly where one of the major problems in the Social Security system lies. The huge returns experienced by those retiring in the 1960's and even beyond were unrealistic. I'm sure that those workers weren't complaining, but this was not a good thing in regard to maintaining the long-term health of the - . Social Security Trust Fund . 24 ~ I VI. Conclusions Because the Social Security system does not collect the necessary information to allow for a more precise study, an analysis such as the one contained in this paper is useful in pointing out past flaws and the possible effects of corrective changes. It would be interesting to see how the return ratios would change if payroll taxes were actually increased to a point where the system really would be self-supporting. I'm sure the results would be very depressing for individuals such as myself who still have a few years of work ahead of us. As I write this, Congress is taking a closer look at some of the financial problems infecting the United States Social Security system. We can only hope that the solutions they propose will not come at the expense of those for whom the system was originally designed. 25 --I REFERENCES [1] Andrews, George H. and John A. Beekman. (1987). Actuarial Projections for the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability Insurance Program of social securita in the United States of America. Ann Arbor, MI: E~wards Brothers, Inc [2] Detlefs, Dole R. and Robert J. Myers. (1992, November). 1993 Guide to Social Security and Medicare. Louisville, KY-:--William M. Mercer, Inc. [3] Grundmann, Herman. (1995, March 8). "Personal letter to the author" . [4] Kellison, Stephen G. (1991). The Theory of Interest. Boston, MA: Richard D. Irwin, Inc. [5] Munnell, Alicia H. (1994). "Social Security". The World Book Encyclopedia. Vol. 18. World Book, Inc. pp. 553-557. [6] Myers, Robert J. and Bruce D. Schobel. (1985). "A Money's Worth Analysis of Social Security Retirement Benefits". Transactions: Society of Actuaries. Vol. 35. St. Joseph, MI: Imperial Printing Company. pp. 533-545. [7] Myers, Robert J. and Bruce D. Schobel. (1993). "An Updated Money's Worth Analysis of Social Security Retirement Benefits". Transactions: Society of Actuaries. Vol. 44. St. Joseph, MI: Imperial Printing Company. pp. 247-270. [8] Social Security Administration Office of Research and Statistics. (1994, August). 1994 Annual Statistical Supplement to the Social Security Bulletin. Washington, DC: Social security Administration. [9] Social Security Administration Office of the Actuary. (1992, February). Social Security Area Population Projections: 1991. Baltimore, NO: Social security Administration. [10] United States. Congress. House. (1993). The Board of Trustees, Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Fund. The 1993 Annual Report of the Federal Old-Age and Survivors Insurance and Disability Insurance Trust Fund. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.