Document 10758525

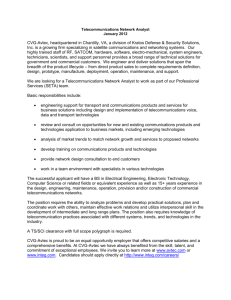

advertisement