Interjurisdictional Placement of Children in the Child Welfare System Improving the Process

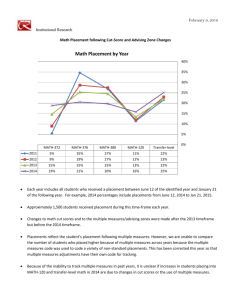

advertisement