Document 10747856

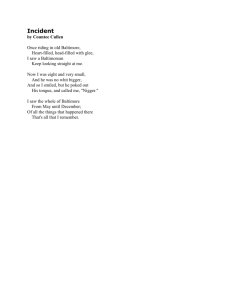

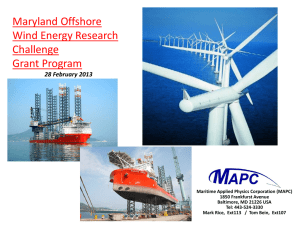

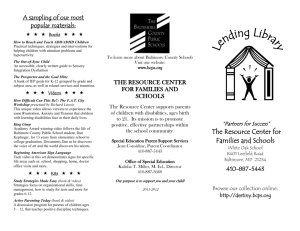

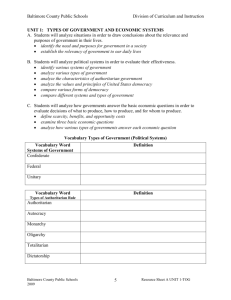

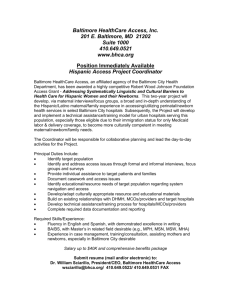

advertisement