HANDBOOK Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures U.S. UNCLASSIFIED

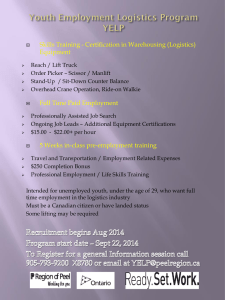

advertisement