Document 10744578

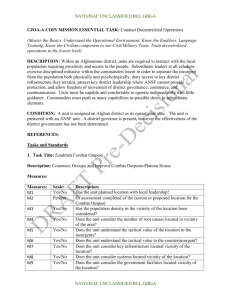

advertisement