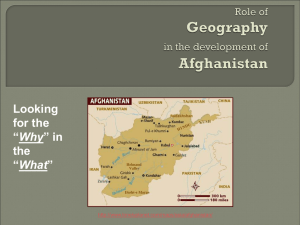

AFGHANISTAN HUMAN RIGHTS AND PROTECTION OF CIVILIANS IN ARMED CONFLICT

advertisement