FRENCH WHITE PAPER D E F E N C E

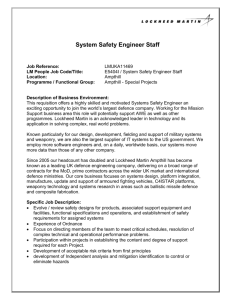

advertisement