داسف یرادا د ینوزرا وا ینراڅ د یدناړو رپ

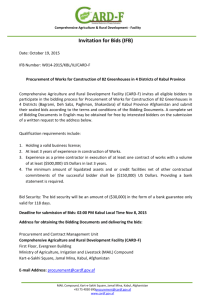

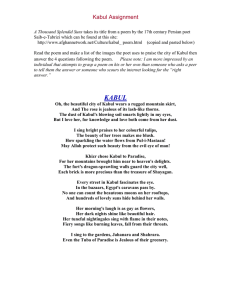

advertisement