Document 10744471

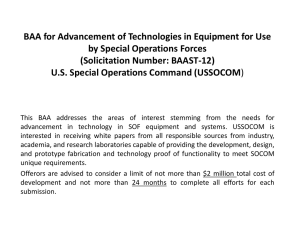

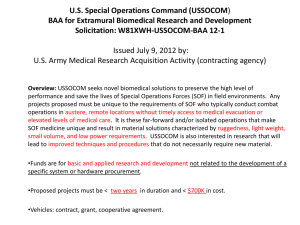

advertisement