Document 10744450

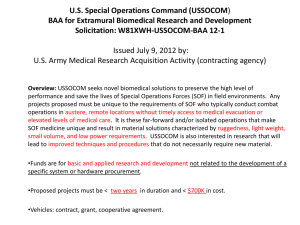

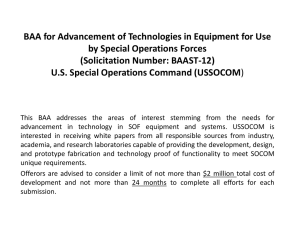

advertisement