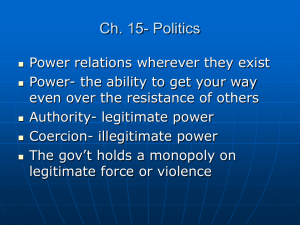

Supreme Court of the United States

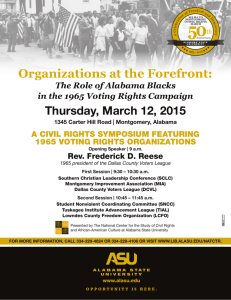

advertisement