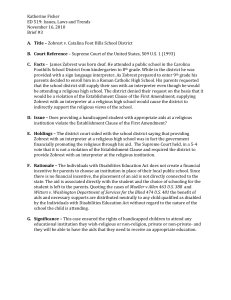

An Analysis of the Systemic Problems Regarding Foreign Language Interpretation in the North Carolina Court System and

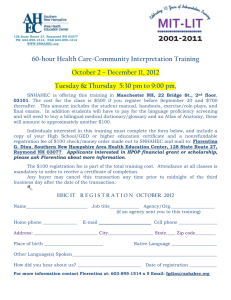

advertisement