Picking Empty Pockets Authors

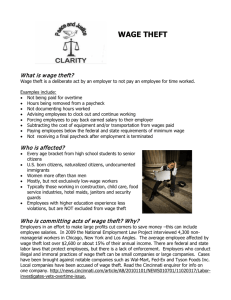

advertisement