High Plains Journal, KS 05-18-07 Managing alfalfa after the freeze

advertisement

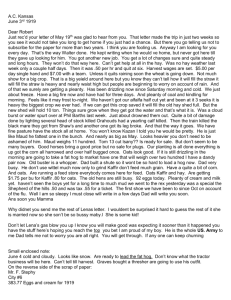

High Plains Journal, KS 05-18-07 Managing alfalfa after the freeze "The alfalfa is way behind. We will take our first cutting once the alfalfa shows buds or blooms. Hopefully it will recover nicely and we will still be able to have three more cuttings after that," said Ted Ewing. By Jennifer Bremer A widespread freeze on alfalfa across the Midwest has forced producers to make management decisions to deal with the loss of the first crop. Wayne County, Iowa producer Ted Ewing said that the first crop will be drastically reduced from normal, but he has a positive outlook for his hay crop for the rest of the year and in the future. "With the increase in ethanol and biodiesel more and more producers are putting land to corn and soybeans," he said. "The extra land that we have will be used for producing more hay." Ewing and his son, Jeff have about 600 acres of ground used for producing organic hay. Most of the hay is an alfalfa and grass mix because that is what their customers demand. "We do have quite a bit of damage from the Easter-time freeze. The alfalfa is way behind. We will take our first cutting once the alfalfa shows buds or blooms," said Ewing. "Hopefully it will recover nicely and we will still be able to have three more cuttings after that." Freeze damage needs to be assessed Iowa State University agronomist Steve Barnhart said that assessing the freeze damage will help producers make management decisions. "If cold injury to established stands only affected some of the early top growth, producers need to determine if the growing point of the stems has been damaged. If there was only leaf damage and the stem tip is recovering normally, follow your normal harvest plans," he explained. However, he said that if the stem tips are permanently damaged, more branches will likely form from the base of the plant. Barnhart said that if the frosted stems were less than 10 inches tall at the time of frost it will take them longer to recover. He recommended that those fields be harvested a week or so later than normal. "It is strongly recommended to dig up random plants to evaluate the condition of the plant crowns and taproots," he said. "Plant crowns should be firm and appear to be living tissue. Healthy taproots are creamy-white in color with a firm texture." Ewing said that he has seen widespread damage in most all his fields in southern Iowa near Russell, but the plants are looking better every day. Making management considerations Barnhart said that producers need to make management considerations for damaged or questionable stands. He suggested to take stem counts in several places in each field to see if there is viable new shoot growth. If there are fewer than 40 stems per square foot, a low, non-economical yield will result. If stem counts are 40 to 55 per square foot, the stand will likely produce less than full yields. An average of more than 55 stems per square foot indicates that the stand is at full production potential. "If a decision is made to terminate the stand either now or after one cutting, plan to follow with a grass-type crop that can benefit from the free fixed nitrogen left behind by the alfalfa," he said. Some suggestions would be to plant corn for silage, which would generate the highest tonnage. Planting oats, barley or spring triticale for forage may be a short-term supplemental forage alternative. Traditional summer annual forage crops, such as sudangrass or one of the millets, are a season-long option that won't need planted until mid-May. Ewing said that they did do some seeding this spring, but their seeding has always been based on need, which gives them the flexibility to spread seed where the stand is a little questionable. He said they have also considered rotating crops more on their farm in order to put more nutrients back in the ground. Since they are producing all organic hay, the only thing that is added to the ground is hog manure. In the future they hope to implement the following rotation having ground in soybeans for one year, corn the second year and follow that with four to five years of hay. "The organic practices already make the soil a higher quality, but by adding a crop rotation, more nutrients will be added to the land, putting more life back into the soil," said Ewing. Hog manure is supplied by three hog buildings located on Ewings' land. The buildings are leased to a former hired man and they use the hog manure as fertilizer on their hay ground. "The arrangement has worked out really well for us," Ewing added. They recently decided to purchase equipment to spread the manure themselves instead of having it custom applied. This will allow for a little more flexibility and will allow them to apply more manure this spring to boost regrowth. Extra acres for renewable fuels causes concern Ewing said he is concerned about a hay shortage this fall since so many farmers are putting their extra acres into corn or soybeans for the renewable fuels industry. "We will continue to raise hay because there will always be a need for hay in the livestock industry," he said. In fact, the additional acres that they will acquire this year from expired CRP contracts will also go toward producing more hay. "The nice thing about CRP acres is that they are already organic and we don't have to let them go through the three year transition to become certified," he added. To become organic the Ewings had to fill out applications and a plentiful amount of paperwork. Ewing credits his wife, Judy, for filling it out and keeping up with the bookwork. They must continually keep track of every little detail such as what seeding is done; how much manure is spread on each field; when it is cut, raked and baled; how it is stored; when it is sold; and how it is transported. "It's a lot of busy work, but there are benefits in the end," Judy Ewing added. Ewing likes to be able to get a 20 percent premium on the organic hay he sells, but when he does the billing he looks at the hay once it is loaded to determine just how good it looks on the truck. He wants his customers to be happy. And happy they must be, because he has repeat customers each year. Last year hay was sold to producers in Pennsylvania, Indiana, Ohio, Wisconsin, Arkansas, Missouri and Iowa. Most of their customers are organic dairy producers, but they will get others also. In a normal growing season, they will produce four to five tons per acre, but they are at the mercy of Mother Nature just like any other farmer. If hay gets rained on or damaged, they use it for their own use and feed it to their 200 head cow herd or the 400 to 500 head of cattle that they background each year. Some hay is also made into haylage and bagged for future feed use. If an insect problem occurs they have to just deal with the problem since organic producers can't spread pesticides. Ewing said that if insects are a problem they will cut the hay as soon as possible, which generally solves the problem. Bordering fields can also cause challenges if drifting of fertilizer, herbicides or pesticides occurs. In that case they keep the hay for their own use as well. Weed problems are also a challenge. Ewing said that they may see more weeds in the first cutting since the alfalfa is so far behind and won't be using up all the nutrients and moisture. He hopes that after the first cutting is baled some of the potential problems will be solved and their crop will grow back, recovering from the damage. In the long run, Ewing will continue to deal with the problems handed to him by Mother Nature and make management decisions to increase the efficiency and yield of his hay crop. Jennifer Bremer can be reached by phone at 641-938-2342 or by e-mail at jbremermaj@hotmail.com.