Inside Higher Ed, DC 03-26-07 Paying by the Program

advertisement

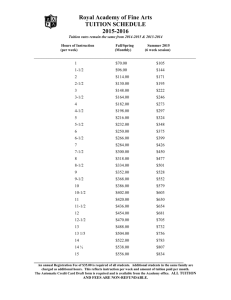

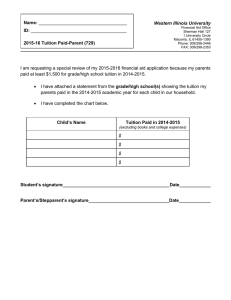

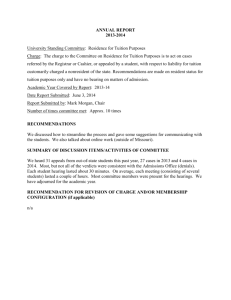

Inside Higher Ed, DC 03-26-07 Paying by the Program As state support lags, tuition rises. It’s a well established phenomenon. But what’s less discussed is the effect that flat state support might be having on the traditional undergraduate tuition model itself. The one-student, one-rate model is somewhat silently slipping away at many public universities nationwide, as institutions increasingly turn toward differential (read: higher) tuition rates for students pursuing specific majors, often those with higher costs of operation. Related stories Just a sample: At its March meeting, the Board of Regents at Arizona State University approved a $250 per semester tuition differential for upperclassmen in the journalism school – which, as of 2008 will be housed in a new, downtown Phoenix facility. At the University of Wisconsin at Madison, the Board of Regents will consider two differential tuition policies, one for the School of Business and the other for the College of Engineering, next month. To the east, UW Milwaukee — now in its third year of differential tuition for undergraduates studying the arts, engineering, business and nursing — just added differential tuition for its architecture students this academic year, and is set for a promised review of its tuition policy this fall. Iowa State University also added differential tuition for upperclassmen in the College of Engineering just this year. But these universities weren’t the pioneers. They join many institutions that already jumped on the pay-for-your-program bandwagon, such as the University of Kansas, which charges extra tuition for undergraduates studying architecture, business, education, engineering, fine arts, journalism and pharmacy, and the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. At Illinois, tuition is $834 more a year for fine arts students, plus $500 extra in books and supplies – and $3,462 extra per year for students studying biology, business, chemistry, engineering (including agricultural engineering), math and computer science, and physics. That means an Illinois resident pursuing one of those fields would be paying $13,428 for tuition annually, compared to the $9,966 paid by a political science major. The College Board, the keeper of all tuition data, doesn’t track variable tuition rates by major, with the figures in its annual report representing the amount paid by a “typical” undergraduate. But several economists tracking tuition policy say, anecdotally speaking, at least, that while differential tuition has been around for quite some time, there has been a significant surge in the introduction of majorspecific undergraduate differential tuition policies over the past five years. At university after university, the stated rationale is the same: Declining state support, administrators say, has forced them to raise more funds from the students who stand to directly benefit. Program or college-specific revenue streams, they argue, enable them to make continuous improvements and maintain competitive programs despite the fiscal straits their institutions may face. But at the same time, many administrators overseeing programs that benefit from differential tuition rates concede that they do worry about the approach — one they often describe as a tack they feel compelled to take. Do differential tuition policies at public universities nationwide, one here, another there, risk eroding some of the basic assumptions – about access, equity, exploration, and the unfettered pursuit of knowledge – that (ideally at least) underlie a traditional, broad-based approach to undergraduate education? “There always was differential tuition for graduate professional programs, these programs that promise great financial reward for students. That has increased a lot in recent years as well,” says Ronald G. Ehrenberg, director of the Cornell Higher Education Research Institute. “At the undergraduate level, the feeling always had been that there should be a single tuition because students should choose what they wanted to study based upon their interests and, if their interests changed, they should be free to shift without having to worry about being priced out.” “Institutions are looking more and more at ways of getting that last dollar out of tuition,” adds Donald E. Heller, associate professor of education and senior research associate at The Pennsylvania State University’s Center for the Study of Higher Education. “If they find out they can or it makes sense to charge students a different tuition, they’re going to see if that works.” “It’s a whole orientation that we’re seeing in higher education. Some people say it’s acting more like a business, and some of what businesses do is differential pricing.” Charging Paul More, or ‘Robbing’ Peter? The tuition structure for undergraduate education has traditionally been somewhat socialistically structured: All students pay the same rate, some subsidizing the more costly educations of others. Of course questions of subsidy can be looked at in multiple ways. Departments like engineering bring a lot of money in the form of research grants into a university. But departments like English tend to have teaching responsibilities for writing and general education that go to the entire student body. Proponents of differential tuition ask why English students should pay higher tuition to subsidize expensive improvements for engineering programs, and argue that in a climate of flat or declining public resources and rising tuition, the burden of funding expensive programs shouldn’t be placed on the typical undergraduate more than it is already. The cost of operating a program, the ability of a program to attract students and the earning potential of graduates all can play roles in setting differential tuition policies. But the worries are also real: Will differential tuition deter low-income students from entering certain fields, further entrenching existing class disparities — even if, as is often the case, the university earmarks a proportion of the new revenue for need-based scholarships? Should earning potential in engineering or the sciences be used as a rationale for adjusting the cost of an undergraduate degree, and what does it mean to charge extra for a major such as fine arts or journalism, where starting salaries are lower and jobs fewer and farther in between? And, if you’re looking at education from a public policy perspective, as a social good, will charging extra for engineering and chemistry majors deter students from entering those fields – just when every other week it seems there’s a new announcement about the need for America to shore up and strengthen its position in the sciences? That’s just the problem, says one dean overseeing a shift in tuition policy. College educations aren’t being viewed as social goods in the way they used to be. “Something happened, probably budgetary more than anything else, 10, 15 years ago. That concept that publicly funded education is a public good changed,” says Mark J. Kushner, dean of the College of Engineering at Iowa State, in its first year of a four-year plan to raise tuition for junior and senior engineering students by $1,750. Annual base tuition for Iowa residents at Iowa State is currently about $5,000. “It changed to ‘public education is an individual good because the students are going out and getting jobs that in large part benefit them as individuals’ as opposed to the big picture of, ‘Yes it does benefit them as individuals but by virtue of them having good jobs and being productive, society is better,’” says Kushner, who thinks the change in perception has helped to fuel decreases in state support. “As you get into that model, and the incremental dollar becomes extremely valuable, then it becomes a little bit more difficult to use the old [tuition] model where you just pool all the money,” says Kushner. The differential tuition for Iowa State’s College of Engineering will enable lab upgrades and major steps forward in faculty hiring. The college, which in a few years will stand to gain $3 to $3.5 million extra per year once the differential tuition plan is fully phased in, is looking to hire five to seven new faculty members every year for the next three to four years. But, those obvious benefits aside, Kushner says that he worries — “very much so” — about whether students there, many of whom do not come from affluent backgrounds, will see the extra cost of Iowa State’s engineering program as a reason to choose another path. “I do worry about equity; I worry about that a lot. Should students really have the opportunity to pay a certain fee and be able to use it for English or use it for history or use it for business?” asks Richard E. Sorensen, immediate past chair of the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business and dean of Virginia Tech’s Pamplin College of Business. Business schools nationwide have increasingly moved toward the differential tuition model in the past five years, especially, he says, as salary demands for business professors have skyrocketed. With no major rebound in public investment on the horizon, the trend, he thinks, will continue. But not all schools will follow suit, he predicts. “I still think there are going to be a lot of schools that don’t do it because they don’t think it’s right. Tuition is tuition is tuition.” Differential tuition at the undergraduate level is still a “minority pricing model,” as Penn State’s Heller puts it. But, in a very select number of fields, the norm may already be shifting. In the Big 10, every public university charges higher tuition for undergraduate business degrees except the University of Minnesota, says Steve Schroeder, director of the Undergraduate Career Center at UW Madison’s School of Business and an author of the proposal for a $500 per semester differential tuition rate there. If approved, it would go into effect this fall. “Yes, it’s competition, but it’s competition in terms of recruiting other faculty members,” says Schroeder, who says that many faculty have left Madison’s business school for offers so high the dean couldn’t even counter-offer. More revenue is needed, Schroeder says, to maintain the quality of the instructors. “It’s the competition, but we’re not proposing a differential tuition just so we can say that we have it and be with our peers. It’s really out of necessity.” “I can tell you with 100 percent certainty: If the chancellor or the governor or whomever decided to give the School of Business X amount of money on an ongoing basis, the dean would drop differential tuition.” Only a handful of students, about 15 total, attended a series of four forums held to discuss the proposed tuition shift at the business school, says Schroeder. Meanwhile, in Madison’s College of Engineering, about 30 to 35 students showed up at a recent session to learn about a similar plan, says Andrew Severance, a junior industrial engineering major who is against the differential tuition concept. “I’m not seeing the hard-pressed times that they’re saying we have. If it is a big problem, why doesn’t the entire university raise tuition,” asks Severance. “If I can be an engineer or I could be a computer scientist, and it would cost me $1,400 extra per year [to study engineering], why would I want to be an engineer?” “It seems,” he says, “like we’re sending the message that an engineering degree is more valuable than any other degree on campus.” Sorensen – whose business school at Virginia Tech does not charge differential tuition for undergraduates – says that, in his experience, students have typically accepted differential tuition policies so long as they’re properly explained. “The students don’t want to pay the extra money, but are going to pay it because they don’t want to get a lesser quality education either,” he says. Many administrators also stress the importance of involving students in how their money is spent, a common practice at colleges that choose to implement differential tuition policies. At UW Milwaukee, school-specific committees, mainly composed of students, propose how the money raised by the differential tuition within that school should be spent, says the associate vice chancellor, Ruth Williams. In the Peck School of the Arts, for instance, some of the funds are used to bring in more professional artists as instructors. UW Milwaukee officials will look closely at the question of whether the tuition changes have affected student choice, Williams says. But enrollment levels, at least, don’t immediately indicate that’s a problem. “This is not the best of all situations. Everybody would prefer that we have enough funding to provide [improvements] without students paying a differential,” Williams says. But, she wonders aloud what other options for continuously investing in improvements really exist within the current climate. “How are we going to be able to do this with campus funds? It’s robbing Peter to pay Paul; there’s no great source of money out there.” — Elizabeth Redden