Bluefield Daily Telegraph, WV 02-09-07

Bluefield Daily Telegraph, WV

02-09-07

Helpful and harmful: Cell phones have changed the way we communicate

By JALETTA ALBRIGHT DESMOND for the Daily Telegraph

My daughters are apparently technologically disadvantaged. I say this with my tongue firmly planted in my cheek, despite claims from my middle-school-age offspring that she suffers from a debilitating social hindrance.

Many young people in my eldest daughter’s age group tote wireless technology that allows them to phone or send text messages. Even some children in the younger grades are carting around high-tech communications.

Text messaging is the premier choice among the younger set, rather than dialing the phone to talk. I think the rest of us find it much easier to use our digits to dial digits and speak the old-fashioned way.

I remember the good old days (groan, here we go) when we picked up the phone and heard intonation and inflection in our interchange with the person on the other end. They weren’t voiceless and abbreviated transmissions full of codes such as “g2g” (got to go) or “POS” (parent over shoulder).

All personality and mood — and most grammar — is now edited out of high-tech dialogue. Not to mention missing eye contact — which first disappeared with the invention of telephones. Now we even lack voice contact, which can easily lead to misunderstandings about written comments tinged with sarcasm or humor, despite the ending punctuation “LOL” (laugh out loud) or “JK” (just kidding or joke).

Stories are rampant about cyber bullying, with guys and girls using keypads to whittle away at the appearance, character or personality of a person sitting right next to them, by bashing them in a text message to a third party. Or there are the cases of kids cheating on exams under the watchful e ye of a teacher who doesn’t notice the flurry of fingers, inputting answers into their cells or PDAs.

Parents may purchase cell phones for children for the same reason I eventually intend to: to provide us both with a safety net of contact. But I also recognize that cell phones provide a certain amount of freedom that stretches that net beyond my comfortable reach: If not heavily monitored or controlled, they could be having 24-hour communications with anyone about anything and from anywhere.

It isn’t like my youth, when the furthest we could escape for privacy was into the other room with a long telephone cord, whispering into the mouthpiece, aware a

parent could walk in at any moment. Our home phone was just that: a phone for the whole home — a communal communication device for everyone, so everyone knew when, how and by whom it was being used.

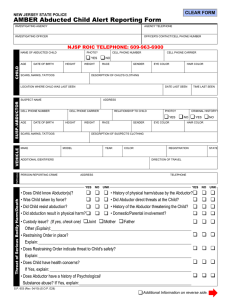

There are stories of how texting and cell phones saved lives in emergency situations. Most notably, a 14-year-old South Carolina girl swiped her alleged abductor’s phone while he slept and sent a text message to her mom saying,

“Hey, mom … I’m being held in a hole,” leading police to her earthen prison and later to her abductor, who faces kidnapping and first-degree criminal sexual conduct charges.

Despite the calls that assure us the kids are safely returning home or let us know school is getting out early, I am warily approaching my daughter’s move into modern communications. I may devise a plan that says, “Check your cell at the door” when she hosts friends because I see how cyber communications interfere with face-toface communications. I’ve noticed her and other young people ignore each other in person to communicate with an absent friend across town.

Adults are also guilty of virtual interruptions, taking phone calls or messages, and ignoring friends and family right across the table.

There is a certain amount of power these devices provide, according to Michael

J. Bugeja from the journalism and communication school at Iowa State

University : “When used appropriately or inappropriately, they reveal character and true genuine relationships. It’s a power we have not earned and we don’t yet know how to use.”

So, as a near techno-phobe parent who sometimes asks my savvier daughter to program my cell, I need to lea rn appropriate use and teach her “celliquette,” or the etiquette of cell use.

Because, as Miro Kazakoff, head of the handset research practice at Bostonbased Compete Inc., said, “It’s appropriate for certain situations. It doesn’t replace face to face.”

Jaletta Albright Desmond, of Bluefield, Va., is a syndicated columnist who writes about faith and family for the Daily Telegraph. Contact her at jdesmond@bdtonline.com.