Point Reyes Light, CA 12-15-06 US won't make cattle tracking mandatory

advertisement

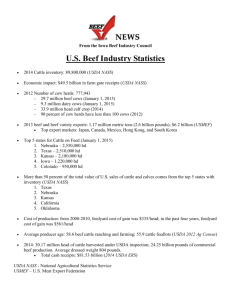

Point Reyes Light, CA 12-15-06 US won't make cattle tracking mandatory Shortly after the first case of mad cow disease was detected in the US in December 2003, Japan – then the largest importer of American beef – cut off business with US cattle producers. Since then, US beef exports have been cut in half, according to USA Today. Despite negative response to the perceived laxness of US regulatory measures – sixty-five nations now having full or partial restrictions on U.S. beef – the government opted recently to keep participation voluntary in its new animal identification and tracking program meant to manage outbreaks and monitor animal health. Participation is mandatory in similar programs in other industrialized nations. The new program, called the National Animal Identification System (NAIS), is designed to “track the births, deaths, co-mingling and all movements of all livestock in the US,” according to USDA. The program targets “animal agriculture”, including livestock and poultry, and could be used to monitor an animal’s medical and nutritional history. “The NAIS is a voluntary program at the federal level and will continue to be a voluntary program at the federal level”, said Ben Kaczmarski of the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service. The USDA made the decision after consulting farmers and ranchers across the country whose businesses are too diverse in their farming practices to make a universal program the optimal choice from an economic or regulatory standpoint, he said. Opposing views Indeed, not all cattle are treated equally. For the majority of US livestock, including West Marin livestock not fed exclusively on grassland, the trip from ranch to supermarket is often a long journey, passing through processing sites in other states before reaching the consumer, according to local ranchers. With organic farming practices such as they are, and with no recent outbreaks of mad cow disease in the US, some West Marin ranchers see little need to spend money monitoring their livestock. The industry estimates the system could cost about $100 million annually. An opposition website called NoNAIS.org posts even higher estimates. “If they’re concerned about the purity of the product, here I am,” said David Evans, owner of Marin Sun Farms. “I can take anyone out and show them where and how exactly my cattle are fed.” Others see the program as a benefit that will ensure foreign markets for US beef exports and bring higher premiums for beef products, in addition to protecting the industry from collapse following an outbreak. Producers selling livestock without age or source data are losing their competitive edge in international markets increasingly defined by quality-control regulations. Consolidate and streamline Though the NAIS is young, established in 2004, the origins of a national animal ID system date back half a century, said Kaczmarski. Smaller-scale tracking operations, like the one implemented in the 1960s to eradicate Brucellosis, an infectious disease which induces headaches and inconstant, or undulating, fevers, have existed for decades at the state and local level. The NAIS is an effort on the federal level to “consolidate and streamline” these smaller programs, he said, citing September 11 and earlier outbreaks of mad cow and foot-andmouth diseases as “approximate causes” for a new integrated federal program. The program, if it achieves full participation, will allow the government to trace the origin of an outbreak, down to the very cow or bird, within 48 hours. The NAIS has three components. The first involves “premises registration”, a process by which all land used to raise livestock receives an ID number. As of early December, 24 percent of lands are registered, close to the 25 percent goal set for January 2007, according to USDA statistics. The two other components of the system, to be driven at the state level, are “animal identification,” a process by which each animal or group of animals is given an ID number and tagged, and establishing onsite “tracing systems,” computer programs which store livestock data. Ranchers may now purchase tagging and tracking systems from the USDA. A global trend Most modern industrialized nations have already developed integrated animal identification systems. Australia and Europe were among the first, developing their infrastructure in the late 90s. Japan and Canada followed suit in the early 2000s. Other countries like Brazil, Uruguay, and Mexico are, like the US, in the process of developing there own systems – with the distinction that theirs are all mandatory. The US system would be alone in keeping participation voluntary. “When you are dealing with US you are dealing with much larger farming system than anywhere on the globe,” said Kaczmarski. America consumes about 95 percent of the beef produced within our borders, despite being the world’s largest importer of beef, according to John Lawrence, a Livestock Economist at Iowa State University and Director of the Iowa Beef Center. For countries where a larger fraction of the total output is exported, there is more financial incentive to regulate their product. “I am disappointed USDA has backed away from mandatory part,” said Lawrence, who believes the program is essential to the process of identifying, isolating and eliminating outbreaks. A voluntary program won’t ensure 100% traceability, “but it is still better than nothing, which is what we had two years ago,” he said. Lawrence also believes keeping participation in the program optional will also slow down innovation in the long run, preventing information that would make American beef products more valuable from circulating in the global marketplace. State and local Although state organizations like the California Cattlemen’s Association are endorsing participation in the program, West Marin cattle ranchers disagree about the value of NAIS. Besides the added cost associated with tagging each of the cattle, estimated at a few dollars a head, some believe it is unnecessary for cattle ranchers who already have high production standards. “I don’t need to hire the government to convince my customers my food is safe,” said Evans. Marin Sun Farms, which sells grass-fed beef locally, actually experienced an upswing after outbreaks because people know his product is safe, he said. Evans believes that the program is just another cost to be suffered by small producers who already have small margins and a comparative disadvantage in the marketplace. To bring his practice in line with the new ID standards was an easy transition for Kevin Lunny of Drakes Bay Family Farms. Lunny supports the program, though he does not believe mad cow disease is a big threat in the US. Even cattle raised on a feedlot in the conventional way in the US is a “good safe product,” he said. “We took a huge hit when the fears about mad cow hit,” with the impacts lasting about six months, said Lunny. Lunny believes the program is valuable from a marketing standpoint, as a way to assure buyers of the quality of the product. But the system’s primary use will be for disease tracking, not for consumer eduction, according to Kaczmarski. “If all the information is tracked, why can’t the consumer use the system as a tool to learn about where the food comes from?” asks Evans. “That would be true food consumerism,” he said.