Chicago Tribune 12-07-06 Food-safety fears revived as Taco Bell pulls onions

advertisement

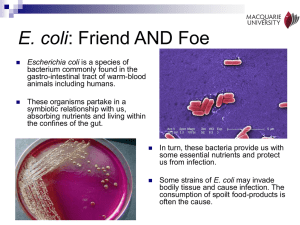

Chicago Tribune 12-07-06 Food-safety fears revived as Taco Bell pulls onions By John Schmeltzer, Tribune staff reporter. Tribune wire services contributed to this report As Taco Bell Corp. pulled green onions from all of its 5,800 U.S. restaurants Wednesday in the wake of an E. coli outbreak linked to some of its restaurants, questions emerged about whether the current testing procedures on produce entering the nation's food system are adequate. The fast-food chain said preliminary testing by an independent lab found three samples of green onions that tested positive for E. coli O157:H7, a potent strain of the bacteria. Taco Bell executives said the tests were not conclusive. But the chain was taking no chances Wednesday when it decided to remove the onions after at least 46 confirmed cases of E. coli sickness were linked to Taco Bells in New Jersey, New York and Pennsylvania over the past few weeks. "In an abundance of caution, we've decided to pull all green onions from our restaurants until we know conclusively whether they are the cause of the E. coli outbreak," said Greg Creed, Taco Bell's president. Taco Bell is a unit of Yum Brands Inc., one of the world's largest restaurant operators. It also operates KFC, Pizza Hut, Long John Silver's and A&W restaurants. Eighteen Taco Bell restaurants, including nine in suburban Philadelphia, three in New Jersey and a half-dozen on New York's Long Island, have been closed for decontamination. Some have reopened since the outbreak was first reported nearly three weeks ago. Taco Bell's E. coli problem comes four months after E. coli contamination forced the nationwide recall of packaged spinach from grocery store shelves and restaurants. Three people died and more than 200 fell ill in the outbreak that was traced to packaged, fresh spinach grown in California. While increased regular testing of the nation's meat supply during the past 20 years has reduced illnesses from meat consumption--a more likely place for E. coli contamination--produce is still tested randomly. Increasing testing may be key to improving the safety of produce, industry experts said. Risks may be greater Robert Tauxe, an official at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, said it may now be riskier to eat produce than in the past. "The outbreaks are bigger and more frequent than they were 20 or 30 or even 15 years ago," he said in the December issue of Nutrition Action, published by the Center for Science in the Public Interest. "Even though we can identify and control outbreaks better than we used to, when contamination does occur with lettuce, spinach, cantaloupe or tomatoes, we can have a big problem on our hands." Each year, the CDC estimates that as many as 33 million Americans become sick from food-borne illnesses. More than 325,000 are hospitalized and 5,000 die. It's estimated that the illnesses cost more than $10 billion in reduced productivity and medical expenses. In 2004, the latest year for which data are available, nearly 400 cases of illness caused by produce were recorded, while there were only 171 outbreaks caused by ground beef, according to data compiled by the Centers for Science in the Public Interest. That is unlikely to change much in the near term because the nation's produce industry can't use "chemical or heat intervention that would be used in other industries" to kill the organisms, according to Sam Beattie, a professor and food safety expert at Iowa State University. Recalls are only remedy Beattie said farmers and the industry can't prevent contamination of field crops. Removing or recalling problem produce at the end of the line is really the only remedy at this point, food safety experts say. "It is very difficult to control what walks across, lands in or slithers through a field. And all of these organisms can carry bacteria. They will deposit their excrement on the plant and it is difficult to detect. "There is precious little the consumer can do once the produce is contaminated and there is precious little the farmer can do to mitigate the contamination," he said. That could be a key reason why Taco Bell, the nation's largest Mexican restaurant chain, so swiftly ordered removal of the green onions from its restaurants. Acting fast after a contamination is about the only option food purveyors have. "Most of the big chains now will err on the side of being overly cautious," said Mac Brand, a consultant with the Hale Group, who said fast-food chains are advised to move swiftly to contain food-borne illnesses. Rob Hardy, another consultant with the Hale Group said, "All the chains realize the risk for the company and investors and so they have elaborate plans designed to prevent contaminated food from entering the distribution system" and even more detailed plans in how to react. Tainted green onions from Mexico were blamed for a 2003 outbreak of hepatitis A in western Pennsylvania that was traced to a Mexican restaurant. Four people died and more than 600 people were sickened after eating the green onions at a Chi-Chi's restaurant. Further tests planned McLane Co., which distributes food to the region's Taco Bells, said federal investigators planned to test green onions, regular onions, cilantro, tomatoes and lettuce from its southern New Jersey warehouse. Authorities also planned to look at a nearby facility of a produce processor, Ready Pac Produce, which handles lettuce, tomatoes, onions and other ingredients for Taco Bell. A Ready Pac spokesman did not immediately return calls. E. coli is found in the feces of humans and livestock. Most E. coli infections are associated with undercooked meat, but the bacteria also can be found on sprouts or leafy vegetables such as spinach. People can spread the germs if they do not thoroughly wash their hands after using the bathroom. E. coli, or Escherichia coli, is a common and ordinarily harmless bacteria, but certain strains can cause abdominal cramps, fever, bloody diarrhea, kidney failure, blindness, paralysis and death. ----------