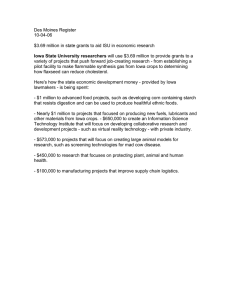

Iowa Farmer Today 12-02-06 Helping crops with self-defense

advertisement

Iowa Farmer Today 12-02-06 Helping crops with self-defense By Tim Hoskins, Iowa Farmer Today AMES -- Researcher Roger Wise is hot on the trail of the controlling agent that makes genes turn on at the correct time to help plants defend themselves. Like many detectives, he relies on what he knows and how it relates to what he doesn’t know. Wise works for USDA’s Agricultural Research Service and is a member of Iowa State University’s Plant Pathology Department. “We hope the work is transferable to corn, beans, rice and other crops,” he says. Wise knows quite a bit about barley and mildew in a state where the farmers grow very little barley. He has researched them for more than 20 years. However, he is the leader of a research team, sponsored by the National Science Foundation, studying how several genes within a plant interact to defend itself. Others on the project include: Steve Whitham, ISU plant pathology; Julie Dickerson, ISU electrical and computer engineering; Dan Nettleton, ISU statistics; and Patrick Schweizer with the Leibniz Institute of Plant Genetics and Crop Plant Research in Gatersleben, Germany. The research focuses on 150-200 genes that react differently, whether or not the plant has a primary-resistance gene. Wise says 160 genes which aid in a plant’s basic defense react to a pathogen with a similar response. “There is a reason that happens,” he says. Part of the project includes Arabidopsis and rice. Rice is a model for cereal crops, and Arabidopsis, a small flowering plant related to cabbage and mustard, is a model for studying plant diseases, genetics and development. Researchers are using those plants because their genomes are mapped. Also, that work might be able to be transferred to crops, such as soybeans and corn. This transference might be possible because some plants share the same genes and gene location. That is helpful when researchers are looking at a plant with nearly 50,000 genes and are trying to focus on 150-200 of them. The genome is mapped for rice. Using a Web site, researchers can map barley, wheat or corn genes to where a similar gene in rice is located. Overall, some of the lessons learned in the experiment might be able to be transferred to corn and soybeans. However, unlike some of these crops, the genomes for corn and soybeans have not entirely been mapped. Researchers are working on mapping corn and soybean genomes. Wise’s work might be useful for those crops after their genomes are mapped. In soybeans, it could help researchers protect the plants from Asian rust, soybean cyst nematode and sudden death syndrome. In addition to working on the gene interactions with pathogens, Wise is part of the Barley Coordinated Agricultural Project (CAP), sponsored by USDA-CSREES. “The goal (of the barley CAP) is to have molecular biologists, geneticists and breeders to work together,” Wise explains. Only one project like this is awarded per year. He says there is an effort to develop a soybean CAP program. Wise says even the barley CAP could yield benefits to Iowa farmers. Whenever there is some breakthrough in one crop, he says someone working in another crop is likely to come along and pick it up. “That is the way the competitive science works,” he says.