The Space Review, MD 09-25-06 Exploring the social frontiers of spaceflight

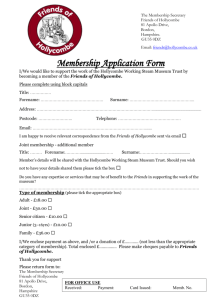

advertisement

The Space Review, MD 09-25-06 Exploring the social frontiers of spaceflight by Dwayne A. Day On September 19–21, the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum and the NASA history office co-hosted a conference titled the Societal Impact of Spaceflight in Washington, DC. The conference featured over thirty speakers on this little-covered topic in space history. The speakers included authors, professional historians, and other serious observers of the space program. What follows is a brief overview of a number of the presentations at the conference. This overview is neither comprehensive nor detailed. It will not include every presentation and only touches on some of the more interesting and intriguing comments (in my opinion) made by a few of the presenters. A number of presentations are excluded not because they were uninteresting, but because I was unable to take notes during the full two and a half days of presentations. Fortunately, the conference organizers intend to eventually produce conference proceedings that will include papers by many of the presenters that will certainly explore these subjects in greater detail. National Air and Space Museum Deputy Director Donald Lopez gave a brief opening talk where he mentioned two upcoming events at the museum. One is the plan to mount a 10-meter-long nose and fuselage section from a 747 to one of the walls of the museum. The museum’s impressive collection of aircraft lacks a vintage 747 and this new exhibit will close part of that gap. Another upcoming exhibition will cover 50 years of space art. The museum owns a vast collection of space art that rarely gets exhibited and this new display will commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the launch of Sputnik. McCurdy also noted that different cultures view space differently. While Americans have a positive image of the frontier, other cultures do not share this image or even the concept of a frontier, and certainly do not view it in the same romantic way as nineteenth century historian Jackson Turner. The keynote lecture was delivered by Howard McCurdy, a historian at American University and author of several books on NASA and social history. McCurdy noted that throughout history humans have changed how they define the world around them. For instance, for much of early American history the wilderness was a dangerous and forbidding place, hostile, and “full of bugs.” But Henry David Thoreau and other writers reimagined the wilderness as a wonderful place and today people visit national parks on their vacations. McCurdy proposed that the same has happened with spaceflight. Space is a hostile environment, more hostile than any place on Earth. And yet space activists and even politicians have portrayed it as a great frontier, a challenge for humanity to explore, rather than a place filled with danger. McCurdy also noted that different cultures view space differently. Discussing a theme that later speakers would revisit, he explained that Americans have a positive image of the frontier. Other cultures do not share this image or even the concept of a frontier, and certainly do not view it in the same romantic way as nineteenth century historian Jackson Turner. These different narratives can shape different policies and public attitudes towards space exploration and development. Roger Launius, chief of the Division of Space History at the Air and Space Museum, spoke about turning points in history. He said that this is one way that historians have of trying to define and shed light on history, but that the definition of a turning point is fuzzy and this tool can obscure as much as it can illuminate. For instance, one survey of American historians identified fifteen turning points in the 20th century. The dropping of the atomic bomb on Japan was number one, and humans landing on the Moon was second, followed by the attack on Pearl Harbor and the Wright Brothers’ airplane flight. However, Launius noted what was not on the list. Ballistic missiles, which made the possibility of instant annihilation possible, were not on this list, perhaps because they did not have a clearly defined moment in time but instead were developed over a period of years. It is important, Launius said, to not simply accept a master narrative that neatly sums up a history and shoves aside other important events and trends. James T. Andrews of Iowa State University spoke about his work writing a book about Konstantin Tsiolkovsky and how he has been used by various groups and people in Soviet society. Joseph Stalin recognized that Tsiolkovsky’s notoriety could be useful for enhancing the image of the Communist Party and the Soviet Union. But, surprisingly to Westerners, Soviet society was not monolithic during the 1950s and 1960s, and there was published criticism of the Soviet government’s campaign to place space on the national stage. Western commentators long noted that the Soviet command-driven economy could deny its citizens consumer goods in order to build rockets, but what has been little recognized was that there were people—artists, writers, and others—who criticized this decision, albeit within limits. Andrew Chaikin, who is perhaps best known for writing a history of the Apollo missions A Man on the Moon and serving as an advisor to the award-winning HBO miniseries From the Earth to the Moon, spoke about the Apollo program’s place in American mythology. Images from Apollo have taken hold in American culture, such as MTV’s appropriation of the image of an astronaut on the Moon. However, Chaikin also noted that the belief among some members of the public that the Moon landings were faked is not new, and as proof he showed a December 1969 article from the New York Times about people who claimed that the landings were actually filmed on a soundstage in the Nevada desert. He also asked a rhetorical question: is it possible that people were so preoccupied with other events during the 1960s—the war in Vietnam, the civil rights movement, assassinations. and social upheaval—that Americans did not celebrate the Apollo landings to the extent that they otherwise might have celebrated? He proposed that the lack of celebration of the event in the 1960s may have contributed to a desire to celebrate it later, noting that many of the people he worked with on the HBO miniseries were truly excited about paying homage to the Moon landing achievement. Is it possible that people were so preoccupied with other events during the 1960s—the war in Vietnam, the civil rights movement, assassinations. and social upheaval—that Americans did not celebrate the Apollo landings to the extent that they otherwise might have celebrated? Valerie Neal, a curator at the Division of Space History at the Air and Space Museum, discussed the popular image of the space shuttle over time. Since its inception in the early 1970s, the shuttle’s image has changed many times and Neal showed examples of NASA advertising over the years. The shuttle was touted as an amazing piece of hardware at first, and Neal noted the surprising lack of human figures in the early NASA artwork of the shuttle. It was supposed to usher in “a new era of routine spaceflight,” but was later billed as a boon to science, then a moneymaking business. When the Challenger was destroyed it had been carrying a communications satellite, yet President Ronald Reagan hailed the deceased astronauts as heroic explorers, resorting to a common theme of the space program even if it did not fit the reality. Later the shuttle was contributing to the goal of “permanent presence in space.” One image that Neal did not discuss is the popular media portrayal of the shuttle as a mistake or failure, an attitude adopted by many journalists after the Columbia accident and bound to dominate the discussion of the shuttle’s impending retirement. John Logsdon, director of the Space Policy Institute at the George Washington University, spoke about space in the post-Cold War environment and asked if the end of the Cold War had changed how the United States conducts its various space programs. Logsdon noted that at the end of the Cold War a “blue ribbon commission” addressed the issue of the future of the American space program and called for substantial changes in the way that the United States operated. For instance, the commission called for essentially ending the separation between the military and intelligence space programs, and reducing the security classification of much of the intelligence space program. This integration did not happen, although some declassification did occur. There were no major changes in the way that the space program was executed, although there were changes in goals and conditions. As one questioner pointed out, the space station was going to die and in many ways it was the end of the Cold War that saved it, making it possible for Russia to become a partner. Logsdon, though, noted that although there have been benefits to this partnership, it is currently American policy to slowly extricate the United States from it. James Hansen, a historian at Auburn University who is perhaps best known in the space community as the author of the Neil Armstrong biography First Man, spoke about how Chinese culture is adapting and developing to that country’s new human spaceflight program. When Yang Liwei was launched into space in late 2003, the Chinese government decided to turn him into a national hero and surprisingly played up his individual achievement in a society that almost never celebrates the individual. Hansen also pointed out that, in contrast to their treatment of Liwei, the Chinese government has kept the two taikonauts who flew on China’s second human spaceflight mission in relative obscurity. According to Hansen, the Chinese government put Liwei on a tour of various Chinese cities where he was often the centerpiece hero of major events attended by tens of thousands of people. When Liwei visited Hong Kong for a “human spaceflight exhibition,” local newspapers and business leaders criticized the visit as propaganda to designed to prop up the Communist government. Although the popular media was cynical about his trip, Hansen said that there was substantial evidence that local Hong Kong residents were excited about Liwei’s visit, and separated his individual achievement from government politics and propaganda. Hansen also said that the Chinese government played up Liwei’s relationship with his young son in a society where the father-son bond is a powerful tradition. Liwei’s son was featured in ceremonies and is himself a hero to children in China. Phil Scranton of Rutgers University talked about how the history of spaceflight has been practiced in the United States. In particular, Scranton noted that there has been almost no attention paid to corporate history in this area. Space achievements have been studied in terms of how NASA built and operated spacecraft, even though the majority of the design, development and manufacturing of spacecraft—and substantial parts of their operation—were done by contractors. Because Air Force leaders did not foresee the incredible range of uses that GPS was later put to, they had no reason to ensure that it advanced quickly. Henry Lambright of Syracuse University talked about the change in how NASA’s leadership viewed the agency’s mission. Throughout the 1960s NASA leaders viewed their mission as exploring space and were ambivalent about environmentalism. But in the early 1970s NASA administrator James Fletcher brought a Mormon’s view of stewardship to the agency and declared that NASA was an environmental agency. He changed the focus of the agency and developed Earth remote sensing programs. Soon NASA gained the “lead agency” role in Earth remote sensing. This was a gradual development with generally positive consequences for the nation as a whole, but somewhat mixed consequences for the agency itself. As Lambright and JPL historian Erik Conway noted, NASA’s increased role in Earth remote sensing also inserted it into the political debate, first about pollution and the Earth’s ozone hole (which conservative skeptics initially denied but later accepted) and then global warming (which conservative skeptics also initially denied, but have now generally accepted). Rick Sturdevant, the historian for Air Force Space Command, spoke about the development of the Global Positioning System (GPS). Sturdevant noted that several factors slowed the system’s progress, resulting in it only becoming fully operational in the early 1990s. One impediment to progress was the fact that GPS initially started primarily as a targeting system for precision weapons. Because Air Force leaders did not foresee the incredible range of uses that GPS was later put to, they had no reason to ensure that it advanced quickly. Another factor delaying its operational availability was the 1986 Challenger accident, which grounded the planned launch vehicle for GPS satellites and forced the Air Force to reopen production lines for expendable launch vehicles. Roger Handberg of the University of Central Florida discussed the bubble in space commerce. Handberg said that the United States used to be totally dominant in space commerce, but over the years has lost much of its lead. This decline has been self-inflicted, Handberg said, through limits on exports and other government policies that have either hindered American competition on the world stage or encouraged competitors to attempt to grab market share from the United States. Glenn Hastedt of James Madison University spoke about reconnaissance satellites and their role in globalization and stabilization. The problem today is that intelligence agencies have moved from looking for secrets to solving mysteries, and reconnaissance satellites are not well-suited to accomplishing this. But in response to a question, Hastedt said that human intelligence was not really the solution to the limitations of satellite reconnaissance. Human sources are difficult to develop and it can take decades to cultivate them. It is not possible to simply decide to acquire better human intelligence, and then go and do it in the short timespan needed to improve intelligence collection in the war on terror. Glen Asner of NASA’s History Division discussed the use of social history to interpret the societal impact of spaceflight. According to Asner, there is virtually no academic research on race relations in the aerospace industry, and he agreed with Philip Scranton that corporate aerospace history is almost nonexistent as well. Andrew Fraknoi, of the Foothill College & Astronomical Society of the Pacific, spoke about the changing attitude toward the study of astronomy in American education. At one time astronomy was a requirement in American schools. This was part of the “mental discipline” model of education, which was based on the belief that study of subjects like Latin, Greek, and astronomy was good for training students how to think, even if they would not later use the knowledge in their lives. However, American science education transformed into the study of biology, chemistry, and physics. Astronomy became a subset of physics, often ignored completely. Now, with the “No Child Left Behind” act, there is no room for astronomy in American schools because astronomy is not included in standardized tests that teachers must prepare their students to take. Margaret Weitekamp, of the Division of Space History at the National Air and Space Museum, spoke about her museum’s collection of “space collectibles.” The museum has over 3500 objects in this collection, which is growing constantly as collectors retire and donate their cherished collectibles to the museum. These objects can include everything from trading cards to dolls to mission pins and polo shirts. She said that she is currently struggling with deciding which objects to include in the museum’s collection and which ones to exclude. Weitekamp is also considering writing a book about why people have collected space objects and what they may signify. Mendell also warned of a potential generational gap in visions of space. Younger people no longer have the shared vision of those raised during the Apollo era. Space is no longer a frontier to be explored and conquered, but instead is a place from which to try and solve Earth’s problems. Asif Siddiqi of Fordham University spoke about pre-Sputnik Russian spaceflight culture and asked a provocative question: why does space achievement not resonate outside of the United States and Russia? Siddiqi noted that Konstantin Tsiolkovsky was a strong believer in eugenics and thought that it was necessary to exterminate imperfect plants and animals. His belief in perfecting humankind extended to his vision of a spacefaring civilization. But this was in many ways an extension of earlier Russian philosophical ideas about traveling into space to retrieve the souls of the dead. Ron Miller, a well-known space illustrator, discussed the role of early science fiction on popular understanding of spaceflight. Miller explained that there were many whimsical stories about journeys to the Moon, but it was Jules Verne who made the first serious effort to apply know scientific and engineering techniques to his fictional story about a journey to the Moon. Alexander Geppert, of the Free University of Berlin, discussed the European perception of spaceflight. Geppert also exhibited one of the more fascinating cultural images during the conference—an ad paid for by the German space industry as part of a 2005 national advertising campaign. Bemoaning the lack of government support for spaceflight, the ad stated “Berlin, wir haben ein Problem…” The phrase, which translates to “Berlin, we have a problem,” is an obvious homage to the famous Apollo 13 phrase. Wendell Mendell, of NASA’s Johnson Space Center, talked about how interest in spaceflight shares many characteristics with religion. He noted that for many years people who were interested in space from an economics standpoint were belittled by the believers. But in recent years we have seen the strange development of rich believers who have sufficient money to express their belief by funding entrepreneurial space companies. However, Mendell also warned of a potential generational gap in visions of space. Younger people no longer have the shared vision of those raised during the Apollo era. Space is no longer a frontier to be explored and conquered, but instead is a place from which to try and solve Earth’s problems. He also mentioned that over the years he has encountered numerous people who felt betrayed by the Apollo program. They believed that it was the beginning of something bold and exciting, but when it ended many of them lost their jobs and their dreams.