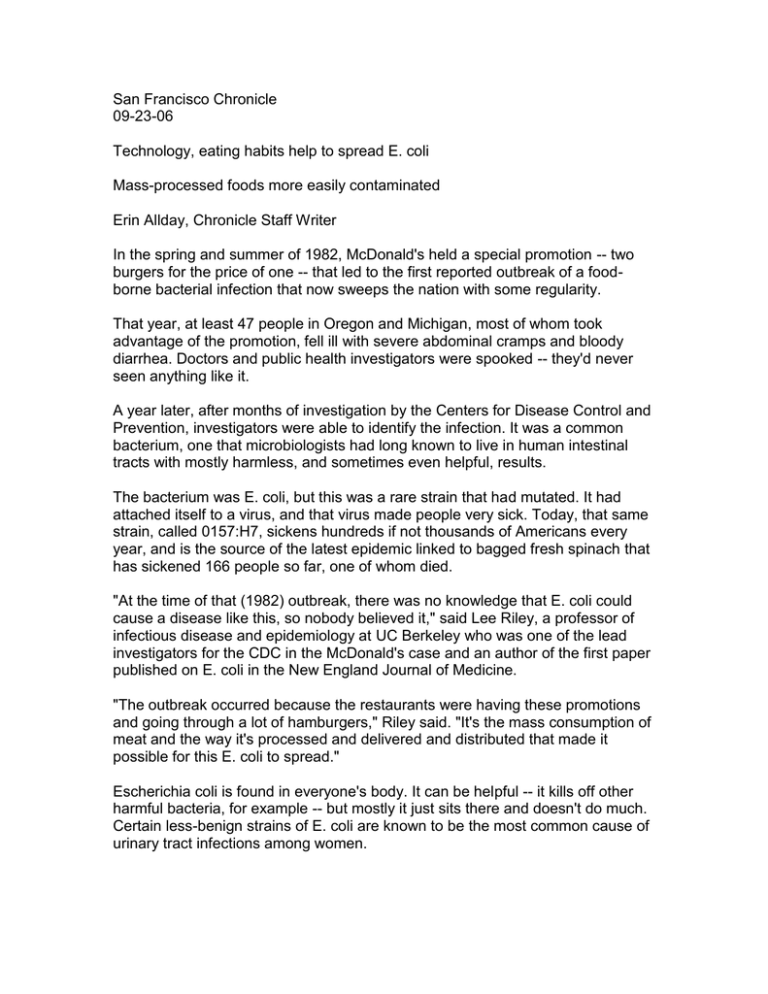

San Francisco Chronicle 09-23-06 Technology, eating habits help to spread E. coli

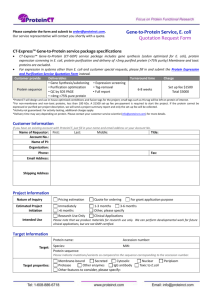

advertisement

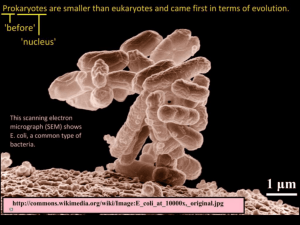

San Francisco Chronicle 09-23-06 Technology, eating habits help to spread E. coli Mass-processed foods more easily contaminated Erin Allday, Chronicle Staff Writer In the spring and summer of 1982, McDonald's held a special promotion -- two burgers for the price of one -- that led to the first reported outbreak of a foodborne bacterial infection that now sweeps the nation with some regularity. That year, at least 47 people in Oregon and Michigan, most of whom took advantage of the promotion, fell ill with severe abdominal cramps and bloody diarrhea. Doctors and public health investigators were spooked -- they'd never seen anything like it. A year later, after months of investigation by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, investigators were able to identify the infection. It was a common bacterium, one that microbiologists had long known to live in human intestinal tracts with mostly harmless, and sometimes even helpful, results. The bacterium was E. coli, but this was a rare strain that had mutated. It had attached itself to a virus, and that virus made people very sick. Today, that same strain, called 0157:H7, sickens hundreds if not thousands of Americans every year, and is the source of the latest epidemic linked to bagged fresh spinach that has sickened 166 people so far, one of whom died. "At the time of that (1982) outbreak, there was no knowledge that E. coli could cause a disease like this, so nobody believed it," said Lee Riley, a professor of infectious disease and epidemiology at UC Berkeley who was one of the lead investigators for the CDC in the McDonald's case and an author of the first paper published on E. coli in the New England Journal of Medicine. "The outbreak occurred because the restaurants were having these promotions and going through a lot of hamburgers," Riley said. "It's the mass consumption of meat and the way it's processed and delivered and distributed that made it possible for this E. coli to spread." Escherichia coli is found in everyone's body. It can be helpful -- it kills off other harmful bacteria, for example -- but mostly it just sits there and doesn't do much. Certain less-benign strains of E. coli are known to be the most common cause of urinary tract infections among women. The first noted case of 0157:H7 actually dates back to 1975, when a woman at Alameda Naval Air Station became mysteriously sick. Doctors at the time couldn't diagnose what ailed her, but they noted the rare E. coli found in her body and sent a sample to the CDC. When the 1982 outbreak occurred, investigators used that sample as further proof that E. coli was responsible for the sickness in the McDonald's cases. Public health officials say it's impossible to know how long E. coli 0157:H7 has been around. People probably were sickened by it for years, or even decades, before doctors identified it. But the reason outbreaks have become more common in the past 25 years, health officials agree, is because technology has been developed to identify and connect strains of bacteria and because the nation's eating habits have changed -- we eat mass-processed foods that make it easier for contaminated products to reach more people. Over the years, technology has become increasingly complex as federal health officials searched for ways to identify outbreaks more quickly. The technique used today, known as PulseNet, allows microbiologists to track the "paternity" of a unique strain of 0157:H7, and, thereby, tell if isolated cases that appear around the country are connected, said Dr. David Acheson, chief medical officer with the federal Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition at the Food and Drug Administration. The first E. coli outbreaks in the United States were in ground beef partly because E. coli bacteria live in cows, and partly because ground beef was among the first food products to be highly processed and mass-distributed via fast-food outlets. Beef from one tainted cow could be mixed with beef from hundreds of healthy cows, and the resulting hamburger patties would all be contaminated. The nation has endured a handful of outbreaks since 1982 -- including one notable outbreak involving hundreds of people who ate at Jack in the Box in 1993 -- but the meat and fast-food industries have adopted policies over the years that make such cases more unusual now. But in the 1990s, the source of the outbreaks spread to fruit and vegetables. In the past decade there have been 20 such outbreaks, including the most recent one. The last nine outbreaks involved leafy greens that were packaged into salad mixes. Those salad mixes have become increasingly popular as Americans, told they need to eat more vegetables, jumped at the convenience of prewashed lettuce and spinach. But the problem with those mixes is the same problem the meat industry ran into -- a very small amount of contaminated vegetable can spread the E. coli bacteria to hundreds or thousands of packages when it's mixed in a processing plant. That was the case with bagged spinach. "Spinach is brought in from many, many farms," Riley said. "So you have an opportunity for a lot of bagged spinach to become contaminated. It's just a massive spread of E. coli, even if the original contamination was limited to one farm." With meat, solving the problem meant simply cooking it at a high enough temperature to kill the bacteria. But raw vegetables may prove more challenging because there's not a lot that can be done once the produce has been contaminated. Washing produce isn't necessarily enough to get rid of E. coli. For now, federal and state investigators are searching farms in the Salinas Valley for clues as to what caused the contamination in spinach. But they may never know the answer. And to some degree, bacteria are always going to be living in our food supply. "We live in a microbial world," said Sam Beattie, a food safety extension specialist at Iowa State University. "Any time you go out into an agricultural field, can you really expect it to be a sterile environment? I don't think so." E-mail Erin Allday at eallday@sfchronicle.com.