Pittsburg Tribune-Review, PA 03-27-06 Cloned pigs to be used in omega-3 study

advertisement

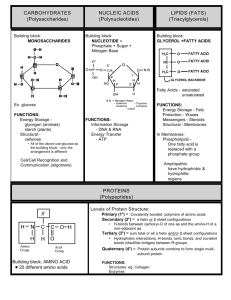

Pittsburg Tribune-Review, PA 03-27-06 Cloned pigs to be used in omega-3 study By Jennifer Bails TRIBUNE-REVIEW Health-conscious consumers might one day have the option of getting their fish fats from the other white meat. Scientists have announced they have cloned pigs carrying a gene necessary to produce omega-3 fatty acids, which are believed to protect against disease and regulate growth and development. Researchers will use the designer pigs to further investigate how omega-3 fatty acids work in the body. The pigs also could provide an alternative dietary source of these essential compounds, said study leader Dr. Yifan Dai, a surgery professor at the University of Pittsburgh. "We always should be looking for ways to improve the product for consumers, and this is clearly one avenue we can take to achieve that," said animal science expert Steven Lonergan of Iowa State University, who wasn't involved in the research. Omega-3 fatty acids are a form of polyunsaturated fats found in fatty fish and fish oils that might help prevent heart disease, cancer, diabetes, arthritis and even depression. More popular foods such as grains, plant-based oils and poultry have less beneficial omega-6 fatty acids. The federal government has no guidelines for intake of omega-3 fatty acids, but nutritionists encourage some people to eat fatty fish such as salmon and herring at least twice a week to balance the typical omega-6 rich American diet. Fatty fish, however, can contain dangerously high levels of toxic mercury. Overfishing threatens scarce marine resources, and rising prices make fish and fish products too expensive for many consumers and farmers. "Health recommendations advise increased consumption of oily fish and fish oils," wrote epidemiologist Eric Brunner of University College London in last week's issue of the British Medical Journal. "We probably do not have a sustainable supply of long chain omega-3 fats." Pork -- or other meat and poultry -- juiced up with fish fats might help resolve that. To achieve the biotech feat, Dai first inserted into pig cells an adapted version of a worm gene aptly named fat-1. The gene produces an enzyme to convert omega-6 fatty acids to omega-3 fatty acids. Dai then shipped his genetically modified pig cells to reproductive technology expert Randall Prather at University of Missouri-Columbia, who cloned the pigs. Results of the study were released Sunday in an online edition of the journal Nature Biotechnology and will be detailed in its April 8 publication.In the study, researchers implanted more than 1,600 embryos into 14 immature female pigs. Twelve of the pigs became pregnant, leading to the birth of six cloned piglets that carried the fat-1 gene. Muscle cells from one of these pigs, which died of heart failure, were used to reclone eight healthy piglets that also had the gene. Five still survive, Prather said.The concentration of omega-3 fatty acids in the cloned piglets was three times higher than in normal piglets but about 10 percent to 15 percent of the amount found in salmon, Dai said. The pigs also had a significantly lower ratio of abundant omega-6 fatty acids to beneficial omega-3 fatty acids.The scientists plan to breed more of these pigs for research purposes, because the benefits of omega-3 fatty acids are still under debate. But don't expect to buy omega-3-rich ham or bacon any time soon. The federal Food and Drug Administration does not allow cloned livestock to enter the food chain. The omega-3-rich pigs would need additional FDA clearance because they are genetically modified, and that is a long and expensive process, Prather said.Also, the pork industry will be reluctant to pursue the technology because of divided public opinion on genetically modified foods, said Iowa State University agriculture professor Max Rothschild, national pig genome coordinator for the U.S. Department of Agriculture."As a science issue, it's fantastic," he said. "As a consumer issue, the jury is still out and not likely to be positive." In the study, researchers implanted more than 1,600 embryos into 14 immature female pigs. Twelve of the pigs became pregnant, leading to the birth of six cloned piglets that carried the fat-1 gene. Muscle cells from one of these pigs, which died of heart failure, were used to reclone eight healthy piglets that also had the gene. Five still survive, Prather said. The concentration of omega-3 fatty acids in the cloned piglets was three times higher than in normal piglets but about 10 percent to 15 percent of the amount found in salmon, Dai said. The pigs also had a significantly lower ratio of abundant omega-6 fatty acids to beneficial omega-3 fatty acids. The scientists plan to breed more of these pigs for research purposes, because the benefits of omega-3 fatty acids are still under debate. But don't expect to buy omega-3-rich ham or bacon any time soon. The federal Food and Drug Administration does not allow cloned livestock to enter the food chain. The omega-3-rich pigs would need additional FDA clearance because they are genetically modified, and that is a long and expensive process, Prather said. Also, the pork industry will be reluctant to pursue the technology because of divided public opinion on genetically modified foods, said Iowa State University agriculture professor Max Rothschild, national pig genome coordinator for the U.S. Department of Agriculture. "As a science issue, it's fantastic," he said. "As a consumer issue, the jury is still out and not likely to be positive." Jennifer Bails can be reached at jbails@tribweb.com or (412) 320-7991.