---

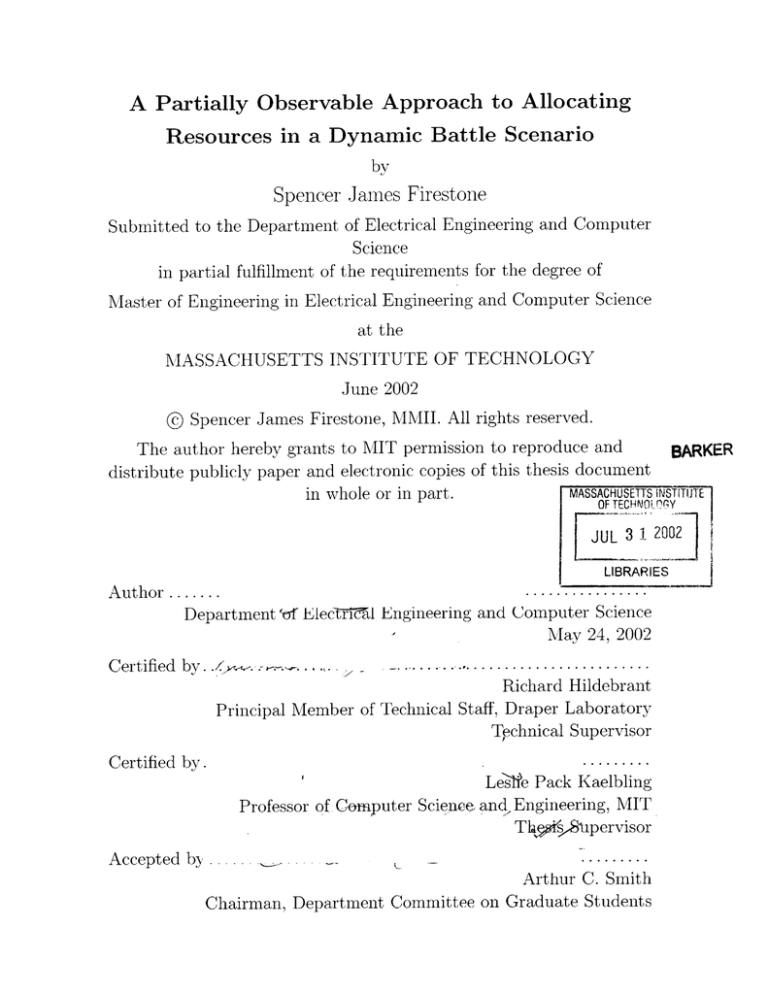

A Partially Observable Approach to Allocating

Resources in a Dynamic Battle Scenario

by

Spencer James Firestone

Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer

Science

in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of

Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

at the

MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

June 2002

@

Spencer James Firestone, MMII. All rights reserved.

The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and

distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document

MASSACHUSETTS

in whole or in part.

BARKER

INSTITUTE

OF TECHN0!L!7'Y

200j

JUL 3

LIBRARIES

. .........

..

A uthor .......

Department' of Elec1TMM1 Engineering and Computer Science

May 24, 2002

C ertified by.....w..

........................

--

Richard Hildebrant

Principal Member of Technical Staff, Draper Laboratory

Technical Supervisor

........

Certified by.

LesThfe Pack Kaelbling

Professor of Computer Science and Engineering, MIT

T9.sSipervisor

........

Arthur C. Smith

Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students

Accepted by -

2

A Partially Observable Approach to Allocating Resources in

a Dynamic Battle Scenario

by

Spencer James Firestone

Submitted to the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

on May 24, 2002, in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Master of Engineering in Electrical Engineering and Computer Science

Abstract

This thesis presents a new approach to allocating resources (weapons) in a partially

observable dynamic battle management scenario by combining partially observable

Markov decision process (POMDP) algorithmic techniques with an existing approach

for allocating resources when the state is completely observable. The existing approach computes values for target Markov decision processes offline, then uses these

values in an online loop to perform resource allocation and action assignment. The

state space of the POMDP is augmented in a novel way to address conservation of

resource constraints inherent to the problem. Though this state space augmentation

does not increase the total possible number of vectors in every time step, it does have

a significant impact on the offline running time. Different scenarios are constructed

and tested with the new model, and the results show the correctness of the model

and the relative importance of information.

Technical Supervisor: Richard Hildebrant

Title: Principal Member of Technical Staff, Draper Laboratory

Thesis Supervisor: Leslie Pack Kaelbling

Title: Professor of Computer Science and Engineering, MIT

3

4

Acknowledgments

This thesis was prepared at the Charles Stark Draper Laboratory, Inc., under Internal

Research and Development.

Publication of this report does not constitute approval by the Draper Laboratory

or any sponsor of the findings or conclusions contained herein. It is published for the

exchange and stimulation of ideas.

Permission is hereby granted by the author to the Massachusetts Institute of

Technology to reproduce any or all of this thesis.

Spencer Firestone

May 24, 2002

5

6

Contents

1

2

1.1

M otivation.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

1.2

Problem Statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

14

1.3

Problem Approaches

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

16

1.4

Thesis Approach

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

17

1.5

Thesis Roadmap

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

18

19

Background

2.1

2.2

2.3

3

13

Introduction

Markov Decision Processes . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

19

2.1.1

MDP Model . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

2.1.2

MDP Solution Method . . . . . . . . . . . .

21

PO M D P . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

22

2.2.1

POMDP Model Extension . . . . . . . . . .

22

2.2.2

POMDP Solutions

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

23

2.2.3

POMDP Solution Algorithms

. . . . . . . .

26

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .

28

2.3.1

Markov Task Decomposition . . . . . . . . .

28

2.3.2

Yost . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

31

2.3.3

Castafion

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

32

Other Approaches Details

Dynamic Completely Observable Implementation

3.1

35

Differences to MTD . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

Two-State vs. Multi-State . . . . . . . . . .

36

3.1.1

3.2

3.3

4

3.1.2

Damage Model

3.1.3

Multiple Target Types

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

37

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

39

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

39

3.2.1

Architecture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

41

3.2.2

Modelling

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

41

3.2.3

Offline-MDP Calculation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

46

3.2.4

Online-Resource Allocation and Simulation . . . . . . . . . .

46

Implementation

Implementation Optimization

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

51

3.3.1

Reducing the Number of MDPs Calculated . . . . . . . . . . .

51

3.3.2

Reducing the Computational Complexity of MDPs

. . . . . .

51

3.4

Implementation Flexibility . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

52

3.5

Experimental Comparison

53

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Dynamic Partially Observable Implementation

4.1

4.2

4.3

Additions to the Completely Observable Model

57

. . . . . . . . . . . .

58

4.1.1

POMDPs

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

58

4.1.2

Strike Actions vs. Sensor Actions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

59

4.1.3

Belief State and State Estimator

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

59

The Partially Observable Approach . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

61

4.2.1

Resource Constraint Problem

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

61

4.2.2

Impossible Action Problem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

64

4.2.3

Sensor Actions

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

66

4.2.4

Belief States . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

67

Implementation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

68

4.3.1

Architecture . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

68

4.3.2

Modelling . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

70

4.3.3

Offline-POMDP Calculations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

72

4.3.4

Online-Resource Allocation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

73

4.3.5

Online-Simulator

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

75

4.3.6

Online-State Estimator . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

75

8

4.4

4.5

5

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

77

4.4.1

Removing the Nothing Observation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

78

4.4.2

Calculating Maximum Action . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

78

4.4.3

Defining Maximum Allocation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

79

4.4.4

One Target Type, One POMDP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

80

4.4.5

Maximum Target Type Horizon . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

80

Experimental Results . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

81

4.5.1

Completely Observable Experiment . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

81

4.5.2

Monte Carlo Simulations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

83

Implementation Optimization

91

Conclusion

5.1

Thesis Contribution.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

92

5.2

Future Work . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

92

95

A Cassandra's POMDP Software

A .1

H eader . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

95

A.2

Transition Probabilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

96

A.3

Observation Probabilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

97

A.4 Rewards . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

97

Output files . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

97

A.6 Example-The Tiger Problem . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

98

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

101

A.5

A.7 Running the POMDP

A.8

Linear Program Solving

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

102

A.9

Porting Considerations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

104

9

10

List of Figures

. . . .

20

A second Markov chain . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . .

20

2-3

A combination of the two Markov chains . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . .

20

2-4

A belief state update . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . .

23

2-5

A sample two-state POMDP vector set . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . .

24

2-6

The corresponding two-state POMDP parsimonious set . . .

. . . .

25

2-7

The dynamic programming exact POMDP solution method.

. . . .

26

2-8

Architecture of the IIeuleau et al. approach

. . . . . . . . .

. . . .

30

2-9

Architecture of the Yost approach, from [9] . . . . . . . . . .

. . . .

31

2-10 Architecture of the Castafion approach . . . . . . . . . . . .

. . . .

32

2-1

A sample Markov chain. ....

2-2

.....................

3-1

A two-state target

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

3-2

A three-state target . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

36

3-3

The completely observable implementation architecture . . .

40

3-4

A sam ple target file . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

42

3-5

A sam ple world file . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

44

3-6

Timeline of sample targets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

45

3-7

A sam ple data file . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

47

3-8

A timeline depicting the three types of target windows

. . .

50

3-9

Meuleau et al.'s graph of optimal actions across time

. . . .

55

3-10 Optimal actions across time and allocation . . . . . . . . . .

56

4-1

The general state estimator

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

60

4-2

The state estimator for a strike action

. . . . . . . . . . . .

60

11

4-3

The state estimator for a sensor action . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

60

4-4

Expanded transition model for M = 3 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

63

4-5

Expanded transition model for M = 3 with the limbo state . . . . . .

65

4-6

The partially observable implementation architecture

. . . . . . . . .

69

4-7

A sample partially observable target file

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

71

4-8

Optimal policy for M = 11 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

82

4-9

Score histogram of a single POMDP target with no sensor action

. .

84

. . . . . . .

85

4-10 Score histogram of a single completely observable target

4-11 Score histogram of a single POMDP target with a perfect sensor action 86

4-12 Score histogram of a single POMDP target with a realistic sensor action 87

4-13 Score histogram of 100 POMDP targets with no sensor action

. . . .

88

4-14 Score histogram of 100 POMDP targets with a realistic sensor action

88

4-15 Score histogram of 100 POMDP targets with a perfect sensor action

89

4-16 Score histogram of 100 completely observable targets

. . . . . . . . .

89

A-1 The input file for the tiger POMDP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

99

A-2

The converged . alpha file for the tiger POMDP . . . . . . . . . . . .

100

A-3

The alpha vectors of the two-state tiger POMDP

. . . . . . . . . . .

101

A-4 A screenshot of the POMDP solver . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

103

12

Chapter 1

Introduction

The task of planning problems in which future actions are based on the current state

of objects is made difficult by a degree of uncertainty of the state. State knowledge

is often fundamentally uncertain, because objects are not necessarily in the same

location as the person or sensor making the observation. Problems of this type can

be found anywhere from business to the military [9, 5j.

For an example of a business application planning problem, consider a scenario

where a multinational corporation produces a product. This product is either liked or

disliked by the general populace. The company has an idea of how well the product

is liked based on sales, but this knowledge is uncertain because it is impossible to

ask every person how satisfied they are. The company wishes to know whether they

should produce more of the product, change the product in some way, or give up on

the product altogether. Of course, an improper action could be costly to the company.

To become more certain, the company can perform information actions such as polls

or surveys, then use this knowledge to guide its actions.

Military applications are even clearer examples of how partial knowledge can

present problems.

In a bombing scenario example, there are several targets with

a "degree of damage" state, anywhere from "undamaged" to "damaged". The goal

is to damage the targets with a finite amount of resources over a period of time.

Dropping a bomb on a damaged target is a waste of resources, while assuming a

target is damaged when it is not can cost lives. Unfortunately, misclassifications are

13

frequent [9]. This thesis will focus on a more developed battle management scenario

in a military application.

1.1

Motivation

Battle management consists of allocating resources among many targets over a period

of time and/or assessing the state of these targets. However, current models of a

battle management world are fairly specific. Some models are concerned only with

bombing targets, while others focus on target assessment.

Some calculate a plan

before the mission, while others update the actions and allocations based on realtime information.

However, a more realistic model could be created by combining

components of these models.

This new model could then be used to create more

accurate and effective battle plans.

1.2

Problem Statement

In a combat mission, the objective of the military is to maximize target damage in the

shortest time with the lowest cost. This thesis will examine a battle scenario where

there are several targets to which weapons can be allocated. The general problem to

be investigated has the following characteristics:

" Objective: The goal of the problem is to maximize the reward attained from

damaging targets over a mission time horizon. The reward is defined as the

value of the damage done to the target less the cost of the weapons used.

" Resources: The resources in this research are weapons of a single type. For

each individual problem, there is a finite number of weapons to be allocated,

Al. Once a weapon is used, it is consumed, and some cost is associated with its

use.

" Targets and States: For each individual problem, there is a finite number of

targets to be attacked. Each target is a particular type, and there are one or

14

more different target types. Each target type has a number of states. There are

at least two states: undamaged and destroyed.

" Time Horizons: The battle scenario exists over a discrete finite time horizon.

Each of the H discrete steps in this horizon is called a time step, t. Each

individual target is available for attacking over an individual discrete finite

time horizon. Target transitions and rewards can only be attained when the

target exists.

" Actions: There are two classes of actions. A strike action consists of using zero

or more weapons on a target in a given time step. There is also a sensor class

of actions, which does not affect the target's state, but instead determines more

information about its state. Sensor class actions are only necessary in certain

models, and this will be discussed in the Observations subsection. Sensor class

and strike class actions are mutually exclusive and cannot be done at the same

time. There are N actions at every time step, where N is the number of targets.

" State Transitions: Each individual weapon has a probability of damaging the

target. Using multiple weapons on a target increases the probability that the

target will be damaged. Damage is characterized by a transition from one state

to another. It is assumed that targets cannot repair themselves, so targets can

only transition from a state to a more damaged state, if they transition at all.

" Allocation: Allocation of resources to targets is dividing the total number of

resources among the different targets. However, allocating x resources does not

imply that all x resources will be used at that time step.

" Resource Constraints: For simplicity, it is assumed that there is no constraint

that limits the number of weapons that can be allocated to any one target at any

time step. The only resource constraint is that the sum of all targets' weapon

allocations is limited to the total number of current resources available.

" Rewards: Rewards are attached to the transitions from one state to another.

Different target classes can have different reward values.

15

* Observations: After each action, an observation is made as to the state of

each target. There are two cases: definitive knowledge of the state of the target,

called complete or total observability, or probabilistic knowledge of the state of

the target, called partial observability.

- Total Observability: In the totally observable class of planning problems, after every action, the state of the targets is implicitly known with

certainty. The next actions can then be planned based on this knowledge.

Only strike actions are necessary in this class of problems.

- Partial Observability: In the partially observable class of planning problems, after every action, there is a probabilistic degree of certainty that a

target is in a given state. It is assumed that a strike action returns no information about the state of the target. In addition, a strike action is not

coupled with a sensor action, so to determine more accurate information

about a target, an sensor class action must be used.

1.3

Problem Approaches

There are current solution methods to battle planning problems in totally observ-

able worlds [71, and solution methods in partially observable ones [9, 5]. However,

these solutions explore slightly different concepts and applications. There are other

differences in battle management solution approaches. Some solutions plan a policy

of actions determined without any real-time feedback [9]. When all calculations and

policies are determined before the mission begins, this is called offline planning. On

the other hand, some solutions dynamically change the policy based on observations

(completely accurate [7] or not [5]) from the world. When the process is iterative,

with observations from the real world or a simulator, this is called online planning.

Some solutions deal with strike actions [7], some focus on bomb damage assessment

(BDA) of targets, some do both [9], and others use related techniques to examine

different aspects of battle management [5].

16

This thesis will look at three seminal

papers which describe different ways to approach the battle management problem,

analyze them in some detail, and combine them into a more realistic model.

Meuleau et al. [7] examine a totally observable battle management world much

like the problem statement described above.

The model consists of an offline and

online portion, and considers only strike actions. The allocation algorithm used is

a simple greedy algorithm combined with Markov decision processes and dynamic

programming.

Yost's Ph.D. dissertation [9] executes much offline calculation and planning to

determine the best policy for allocation of weapons to damage targets and assess

their damage using sensors in a partially observable world. His allocation method is

a coupling of linear programming and partially observable Markov decision processes.

Castafion's [5] looks at a different aspect of the battle management world. His

focus is on intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), where target type

is identified.

This is closely related to determining the state of a target in a par-

tially observable world, which is the topic of this thesis. He uses online calculations

with partially observable Markov decision processes, dynamic programming, and Lagrangian relaxation to allocate sensor resources.

1.4

Thesis Approach

To establish a baseline for comparison, we begin by creating a simple totally observable model. The model will be almost identical to the one in Meuleau et al.'s paper,

with a few extensions and clarifications. The model will consist of both online and

offline phases. Examples similar to the paper will be run and compared to the paper's results. The model will be extended by expanding the initial implementation to

operate in a partially observable world with additional characteristics. Then we will

run experiments, analyze and compare results to prior work, and draw conclusions

from the experiments.

Another graduate student, Kin-Joe Sham, is concurrently working in the same

problem domain. However, he is focusing on improving the allocation algorithms and

17

adding additional constraints to make the model more realistic. We have collaborated

to implement the totally observable model, but from there, our extensions are separate, and the code we created diverges. Future work in this problem domain could

combine our two areas of research, as we shared code for the completely observable

implementation and started with the same model for our individual contributions.

1.5

Thesis Roadmap

The remainder of this thesis is laid out as follows: Chapter 2 gives background into

totally and partially observable Markov decision processes. It also describes the three

other papers in much more depth. Chapter 3 discusses the totally observable model

fashioned after Meuleau et al.'s research, including the differences between their approach and ours, additional considerations encountered while developing the model,

implementation optimizations, and experimental result comparisons. Chapter 4 develops the partially observable model, comparing it to the completely observable one

defined in the previous chapter. It discusses interesting new implementation optimizations and then presents experimental results and analysis of different real-world

scenarios.

Chapter 5 describes the conclusions drawn from this research and pos-

sible future extensions to the project. Appendix A contains a detailed description

Cassandra's POMDP solver application.

18

Chapter 2

Background

Our work is founded on totally and partially observable Markov decision processes,

so we begin with a description of them. With the understanding gained from those

descriptions, the other approaches can be explained in more detail.

2.1

Markov Decision Processes

A Markov decision process (MIDP) is used to model an agent interacting with the

world [6].

The agent will receive the state of the world as input, then generate

actions that modify the state of the world. The completely observable environment is

accessible, which means the agent's observation completely defines the current world

state [8].

A Markov decision process can be viewed as a combination of several similar

Markov chains with different transition probabilities. The sum of the probabilities on

the arcs out of each node must be 1. As an example, a sample Markov chain is shown

in Figure 2-1. In this chain, there are four states, a, b, c, and d, which are connected

with arcs labelled with transition probability from state i to

j,

Tj.

Figure 2-2

displays these same four states, but with different transition probabilities. If figure 21 is considered to be a Markov chain for action a 1 and figure 2-2 represents a chain

for action a 2 , the combination of the two is shown in figure 2-3. Now different paths

with different probabilities can be taken to get from one state to another by choosing

19

Pac

a

~

Pab=0.6

0-4

Pca=0.3

b=Id=09P

0.

cd

b

Figure 2-1: A sample Markov chain

Pac=7

pba=IPdI

I

b

b - -d

Pdc=.2

Figure 2-2: A second Markov chain

Pac1

0-4

Pac2=

PeP

Pb=11

ba2

Pab1=0.

=0

6

pIcd2I

Pdcl=0-9

Pbcl=

b

d

PdbI=

0

.IPc2=0.2

Figure 2-3: A combination of the two Markov chains

20

different actions. If the states have reward values, it is now possible to maximize

reward received for a transitions from state to state by choosing the appropriate

action with the highest expected reward. This is a simplification of an MDP.

2.1.1

MDP Model

An MDP model consists of four elements:

" S is a finite set of states of the world.

* A is a finite set of actions.

" T : S x A -

H(S) is a state transition function.

For every action a E A,

and state s E S, the transition function gives the probability that an object

will transition to state s' E S. This will be written as T(s, a, s'), where s is

the original state, a is the action performed on the object, and s' is the ending

state.

" R : S x S

-+

R is the reward function. For every state s E S, R is the reward

for a transition to state s' E S. This will be written as R(s, s').

2.1.2

MDP Solution Method

This thesis is concerned with problems of a finite horizon, defined as a fixed number

of discrete time steps in the MDP . Thus the desired solution is one in which a set of

optimal actions, or a policy, is found. An optimization criterion would be as follows:

-H-1~

maxE E rt,

t=O

where rj is the reward attained at time t. Since we assume that the time horizon is

known for every target, this model is appropriate.

To maximize the reward in an MDP, value iteration is employed. Value iteration

is a dynamic programming solution to the reward maximization problem. The procedure calculates the expected utility, or value, of being in a given state s. To do

21

this, for every possible s' it adds the immediate reward for being in s to the expected

value of being in the new state s'. Then value iteration takes the sum of these values,

weighted by their action transition probabilities, for a given action a. The expected

value, V(s) is set to be the maximum value produced across all possible actions:

V(s) = max

T(s, a, s')[R(s, s') + V(s')].

(2.1)

A dynamic programming concept is used to apply equation 2.1 to multiple time

steps. By definition, the value of being in any state in the final time step, H, is

zero, since there cannot be a reward for acting on a target after the time horizon

has expired. Next, the H - 1 time step's values are calculated. For this iteration of

equation 2.1, V(s') refers to the expected value in the next time step, H, which is

zero. The expected value for every state is calculated in time step H - 1, then these

values are used in time step H - 2. The value iteration equation is adjusted for time:

V(s) = max E T(s, a, s')[R(s, s') + 11(s')],

where VH(s) = 0. In this manner, all possible expected values are calculated from the

last time step to the first using the previously calculated results. The final optimal

policy is determined by listing the maximizing action for each time step.

2.2

POMDP

The world is rarely completely observable. In reality, the exact state of an object may

not be known because of some uncertain element, such as faulty sensors, blurred eyeglasses, or wrong results in a poll, for example. This uncertainty must be addressed.

2.2.1

POMDP Model Extension

A POMDP model has three more elements than that of the MDP:

. b is the belief state, which is a set of probability distributions over the states.

22

Observation

Action

__gon-

BStaee

Stat

Belief

State

Updater

Figure 2-4: A belief state update

Each element in the belief state b(s), for s E S contains the probability that

the world is in the corresponding state. The sum of all components of the belief

state is 1. A belief state is written as:

[ b(so) b(s1 ) b(s 2 )

...

b(slsl)

* Z is a finite set of all possible observations.

* 0 :SxA

-+

-I(Z) is the observation function, where O(s, a, z) is the probability

of receiving observation z when action a is taken, resulting in state s.

In the totally observable case, after every action there is an implied observation

that the agent is in a particular state with probability 1. But since state knowledge is

now uncertain, each action must have an associated set of observation probabilities,

though every observation does not necessarily need to correspond to a particular state.

After every action, the belief space gets updated dependent on the previous belief

space, the transition probabilities associated with the action, and the observation

probabilities associated with the action and the new state [3], as shown in figure 2-4.

2.2.2

POMDP Solutions

Solving a POMDP is not as straightforward as the dynamic programming value iteration used to solve an MDP. Value functions at every time step are now represented as

a set of ISI-dimensional vectors. The set is defined as parsimonious if every vector in

the set dominates all other vectors at some point in the ISI-dimensional belief space.

A vector is dominated when another vector produces a higher value at every point.

23

V(b)

72

7

0

...........

.

73................. ................

o

b1

(dead)

(alive)

Figure 2-5: A sample two-state POMDP vector set

Ft represents a set of vectors at time step t, -y represents an individual vector in the

set, and F* represents the parsimonious set at time t. The value of a target given a

belief state, V(b), is the maximum of the dot product of b and each -y in F*. There

will be one parsimonious set solution for each time step in the POMDP. Like MDPs,

POMDPs are solved from the final time step backwards, so there will be one 17* for

each time step t in the POMDP, and the solutions build off of the previous solution,

t-.

The value function of the parsimonious set is the set of vector segments that

comprise the maximum value for every point in the belief space. The value function

is always piecewise linear and convex [2].

Figure 2-5 shows a sample vector set for a two-state POMDP. With a two-state

POMDP, if the probability of being in one of the states is p, the probability of being

in the other state must be 1 - p. Therefore the entire space of belief states can be

represented as a line segment, and the solution can be depicted on a graph. In the

figure, the belief space is labelled with a 0 on the left and a 1 on the right. This is

the probability that the target is in state 1, dead. To the far left is the belief state

that the target is dead with probability 0, and thus alive with probability 1. To the

far right is the belief state that the target is dead with probability 1, and thus alive

24

V(b)

0

(dead)

(alive)

Figure 2-6: The corresponding two-state POMDP parsimonious set

with probability 0. Each vector has an action associated with it. Distinct vectors

can have the same action, as the vector represents the value of taking a particular

action at the current time step, and a policy of actions in the future time steps. The

dashed vectors represent action a1 , the dotted vectors represent action a2 , and the

solid vectors represent action a3 .

There are six vectors in this set, but not all are useful.

Both 'y4 and ye are

completely dominated, so are not be included in the final optimal value function. It

is useful to note that there are two types of vector domination. The first is complete

domination by one other vector, shown in the figure as 'y4 is completely dominated at

every point in the belief space by 73. The second is piecewise domination, shown in

the figure as

Y6

is dominated at various points in the belief space by 71i, 72 73 and

75 Various solution algorithms make use of the differences between these two types

of domination to optimize computation time.

Figure 2-6 shows the resulting parsimonious set and the sections that the vectors

partition the belief space into. In this particular problem, the belief space has been

partitioned into four sections, with a1 being the optimal action for the first and

fourth sections, a2 producing the optimal value for the second section, and a3 being

25

F*

t -11

a, z.a)VvE

ral

ral

al

-*-F

][aAl

a2j

iFa2P

f

e

e

ra

l

ra

A

][ fah

2

.

falAl

U

Figure 2-7: The dynamic programming exact POMDP solution method

the optimal action for the third. The heavy line at the top of the graph represents

the value function across the belief space.

2.2.3

POMDP Solution Algorithms

How the solutions for each time step are created is dependent on the POMDP solution

algorithm used. However, this thesis does not focus on POMDP solution algorithms,

but rather uses them as a tool to produce a parsimonious set of vectors. This section will discuss general POMDP solution algorithms at a high level, and also the

incremental pruning algorithm used in this research. Cassandra's website [2] has an

excellent overview of many solution algorithms.

General Algorithms

There are two types of POMDP solution algorithms: exact and approximate. Exact

algorithms tend to be more computationally expensive, but produce more accurate

solutions. Ve chose among several exact dynamic programming algorithms.

26

The current general solution method for an exact DP algorithm uses value iteration

for all vectors. The algorithm path can be seen in figure 2-7. Every -Y in the previously

calculated parsimonious set F*

is transformed to a new vector given an action a and

an observation :, according to a function defined as

(-y, a, -). These vectors are then

pruned, which means that all vectors in the set that are dominated are removed. This

produces the set of vectors F'. This is done for all possible actions and observations.

Next, for a given action a, all observations are considered, and the cross-sum, (,

of every F is calculated. This vector set is once again pruned, and this produces 1a.

This is done for all a C A. Finally, the algorithms take the union of every 1a set,

purge those vectors, and produce the parsimonious set F*.

The purging step involves creating linear programs which determine whether a

vector is dominated by any other vector at some point. However, this is optimized by

performing a domination check first. For every vector, the domination check compares

it against every other vector to determine if a single other vector dominates it at every

point in the belief space. If this is the case, the vector is removed from the set, making

the LPs more manageable.

Several algorithms were considered for this research. In 1971, Sondik proposed

a complete enumeration algorithm, then later that year updated it to the One-Pass

algorithm. Cheng used less strict constraints in his Linear Support algorithm in 1988.

In 1994, Littman et al. came up with the widely used Witness algorithm, which is the

basis for the above discussion of a general POMDP solution method. Finally, in 1996,

Zhang and Liu came up with an improvement on the Witness algorithm, calling it

incremental pruning. This is currently one of the fastest algorithms for solving most

classes of problems [4].

Incremental Pruning

The incremental pruning algorithm optimizes the calculation of the IF sets from the

17 sets. The way to get the F' sets is to take the cross sum of the action/observation

27

vector sets and prune the results, in the following manner:

T4purge

@ r

this is equivalent to:

purge(ra

2a

..

Za

IZI.

where k

Incremental pruning notes that this method takes the cross sum of all possible

vectors, creating a large set, then pruning this large set.

However, this is more

efficiently done if the calculation is done as follows:

p pruage(... purge(purge(1

9

1a7)

D r)

(D r

A more detailed description of the algorithm is contained in Cassandra et al.'s published paper

[4]

which reviews and analyzes the incremental pruning algorithm in

some depth.

2.3

Other Approaches Details

As mentioned before, three papers have looked at problems similar to the one this

thesis discusses. Each of these papers has had significant impact on the creation of

this model.

2.3.1

Markov Task Decomposition

Meuleau et al.'s paper focuses on solving a resource allocation problem in a completely

observable world.

Meuleau et al.

use a solution method they call Markov Task

Decomposition (MTD), in which there are two phases to solving the problem:

an

online and an offline phase, thus making it dynamic. The problem they choose to

solve is to optimally allocate resources (bombs) among several targets of the same

type such that at the end of the mission, the reward obtained is maximized. Each

28

target is accessible within a time window over the total mission time horizon, and

has two states: alive or dead. There is one type of action, a strike action, which is

to drop anywhere from 0 to M bombs on a target. Each bomb has a cost and an

associated probability of hitting the target, and the probability of a successful hit

goes up with the number of bombs dropped according to a noisy-or damage model,

which assumes each of the a bombs dropped has an independent chance of causing

the target to transition to the dead state.

The offline phase uses value iteration to calculate the maximum values for being

in a particular state given an allocation and a time step, for all states, allocations,

and time steps. The actions associated with these maximum values are stored for use

in online policy generation.

In the online phase, a greedy algorithm calculates the marginal reward of allocating

each remaining bomb to a target, using the previously calculated offline values. At the

end of this step, every target i will have an allocation mi. This vector of allocations

is passed to the next component of the online phase, the policy mapper. For each

target, the policy mapper looks up the optimal action for that target's time step

ti, mi, and state si. Then the policy mapper has a vector of actions consisting of

one action for each target. These actions are passed to a simulator which models

real world transitions. Every action has a probabilistic effect on the state, and the

simulator calculates each target's new state, puts them into a vector, then passes this

state vector back to the greedy algorithm.

The greedy algorithm then calculates a new allocation based on the updated

number of bombs remaining and the new states, the policy mapper gets the actions

for each target from the offline values, sends these actions to the simulator, and so

on. The online phase repeats in this loop until the final time step is reached.

Figure 2-8 shows the MTD architecture. The first step is the greedy algorithm.

For every target, the greedy algorithm phase uses the target's current state s and time

step t to calculate the marginal reward for adding a bomb to the target's allocation.

The target with the greatest marginal reward mA has its allocation incremented by

one. Once a bomb is allocated to target x, that target's marginal reward, mrn

29

is

Corresponding

actions 1

4

Policy

Actions

sMapper

s, t, m

indexes

Offline

World

Allocations

Dynamic

Programming

Corresponding

values,

P

4 -

s, t, mA

indexes

Greedy

Algorithm

States

Figure 2-8: Architecture of the Meuleau et al. approach

recalculated. When all bombs have been allocated, every target has an allocation. A

vector of allocations is then passed to the policy mapper module.

The policy mapper module in the figure uses the same s and t as the greedy

algorithm used, but now uses each target's allocation from the allocation vector. The

action corresponding to the maximum value for that target's s, t, and m is returned

to the policy mapper, which then creates a vector holding an optimal action for every

target. This vector is then passed to the world.

The world, whether it is a simulator or a real life scenario, will perform the

appropriate actions on each target. The states of these targets are changed by these

actions according to the actions' transition models. The world then returns these

states to the greedy algorithm, incrementing the time step by one. This loop repeats

until the final time step is reached.

The paper lists three different options for resource constraints. The first is the

no resource constraints option, in which each target is completely decoupled, and

there is no allocation involved, so only the offline part is necessary. Each target has

a set of bombs that will not change over the course of the problem. In the second

option, global constraints only, the only resource constraint observed is such that the

total number of bombs allocated must not be more than the total number of bombs

for the entire problem.

The third alternative is the instantaneous constraints only

30

Current object values,

resource marginal costs

Initial

Policies

POMDP

MASTER LP

(1 per object type)

available resources

object constraints

optimal policy for

current costs

Improving policies

Quit when no

improving policies

are found

Figure 2-9: Architecture of the Yost approach, from [9]

option, in which there are a limited number of weapons that can be simultaneously

delivered to any set of targets (i.e., plane capacity constraints). This thesis uses the

second option, global constraints only, based on its simplicity and the possibility for

interesting experiments.

2.3.2

Yost

Yost looks at the problem of allocating resources in a partially observable world.

However, all calculations are done offline. He solves a POMDP for every target, and

allocates resources based on the POMDPs' output. Then his approach uses a linear

program to determine if any resource constraints were violated. If there are resource

constraint violations, the LP adjusts the costs appropriately and solves the POMDPs

again, until the solution converges.

Figure 2-9 shows Yost's solution method. It shows that an initial policy is passed

into the Master LP, which then solves for constraint violations.

The new updated

rewards and costs are passed into a POMDP solver, which then calculates a new policy

based on these costs. This policy goes back into the Master LP, which optimizes the

costs, and so on, until the POMDP yields a policy that cannot be improved within

the problem parameters. This is all done completely offline, so it does not apply to a

dynamic scenario.

31

POMDP

Solver

Updated

costs

Corresponding

values

Actions

Initial

Information

Lagrangian

Relaxation

World

State

Observations

Figure 2-10: Architecture of the Castafion approach

2.3.3

Castafion

Castafion does not deal with strike actions, but instead uses observation actions to

classify targets. Each target can be one of several types, and the different observation

actions have different costs and accuracies. He uses the observations to determine the

next action based on the POMDP model, thus his problem is dynamic.

He has two types of constraint limitations. The first is, again, the total resource

constraint.

He also considers instantaneous constraints, where he has limited re-

sources at each time step. He uses Lagrangian relaxation to solve the resource constraint problems. The entire problem is to classify a large number of targets. However,

he decouples the problem into a large number of smaller subproblems, in which he

classifies each target. Then he uses resource constraints to loosely couple all targets.

But by doing the POMDP computation on the smaller subproblems, he reduces the

state space and is able to use POMDPs to determine optimal actions.

Figure 2-10 depicts Castafion's approach. An initial information state is passed

to the Lagrangian relaxation module.

This in turn decouples the problems into

one POMDP with common costs, rewards, and observation probabilities. Then the

POMDP is solved, and the relaxation phase creates a set of observation actions based

on the results. The world returns a set of observations and the relaxation phase then

uses this to craft another decoupled POMDP, and so on until the final time step.

32

This approach is conducted entirely online. Castaion has efficiently reduced the

number of POMDPs for all targets to one, but because the problem is dynamic, a

new POMDP must be solved at every time step. His problem is one of classification,

so the state of an object never changes. Thus, transition actions do not exist, and

observation actions cause a target's belief state to change.

33

34

Chapter 3

Dynamic Completely Observable

Implementation

To analyze a new partially observable approach to the resource allocation problem, we

begin by expanding the totally observable case. Though most of the ideas presented

in this chapter are from Meuleau et al.'s work, it is necessary to understand them, as

they are fundamental to the new approach presented in this thesis.

The problem that this chapter addresses is one in which there are several targets

to bomb and each is damaged independently. The problem could be modelled as an

MDP with an extremely large state space. However, this model would be too large

to solve with dynamic programming [7]. Thus, an individual MDP for each target is

computed offline, then the solutions are integrated online. The online process is to

make an overall allocation of total weapons to targets, then determine the number

of bombs to drop for each target. The first round of weapons are deployed to the

targets and the new states of the targets are determined. Bombs are then reallocated

to targets, a second round of weapons are deployed, and so on, until the mission

horizon is over.

35

S ={undamaged, damaged}

.5 ..

0

[0

1

'0

501

0

Figure 3-1: A two-state target

S ={undamaged, partially damaged, destroyed}

T =

.6 .3 .1

0 .7 .3j, R=

0 0 1

0 25 501

0 0 20

0 0 0

Figure 3-2: A three-state target

3.1

Differences to MTD

The research presented in Meuleau et al.'s paper is complete, and the problem domain

can be expanded to include partially observable states. However, other enhancements

were made to the problem domain, including implementing and testing with multistate targets (defined as targets with three or more states), updating the damage

model, and allowing for multiple target types.

3.1.1

Two-State vs. Multi-State

Though Meuleau et al.'s model and calculations are of a general nature and can

be used with multi-state targets, the paper only discusses a problem in which the

targets are one type; and this target type has two states: alive and dead. However,

in real-world problems, there will often be more than two states. A trivial example

is a 4-span bridge in which the states range from 0% damaged to 100% damaged in

25% increments [9]. The implementation presented in this thesis can handle multiple

states. It is simple enough to extend the model from two states to multiple states.

All that is involved is adding a state to the S set, increasing the dimensions of the

T matrix by one, and increasing the dimensions of the R matrix by one as well.

For example, figure 3-1 presents a simple target type with two states: undamaged

36

Description

State

Si

Undamaged

25% damaged

50% damaged

75% damaged

Destroyed

S2

S3

S4

S5

Table 3.1: Sample state descriptions

and damaged. Figure 3-2 presents a target with three states: undamaged, partially

damaged, and destroyed. The new T is a 3 x 3 matrix, and the R has more reward

possibilities as well.

3.1.2

Damage Model

Meuleau et al. use a noisy-or model, as described below, in which a single hit is

sufficient to damage the target, and individual weapons' hit probabilities are independent. The state transition model they use for a two state target with states u

undamaged and d = damaged is the following:

T(s, a, s') =

0

if s = d and s' = u

1

if s = d and s' = d

q

if s = u and s' = u

1

if s = u and s' = d

-

The transition probability for a target from state s to state s' upon dropping a bombs

is determined by the probability of missing, q = 1 - p, where p is the probability of

a hit.

To extend the model to multiple states, it is necessary to analyze what an action

actually does to the target. Consider a target with five states, si through s5 , as shown

in table 3.1. A state that is more damaged than a state si is said to be a "higher"

state, while a state that is less damaged is a "lower" state.

Each bomb causes a transition from one state to another based on its transition

matrix T. Since the damage from each bomb is independent and not additive, when

37

multiple bombs are dropped on a target, each bomb provides a "possible transition"

to a state. The actual transition is the maximum state of all possible transitions.

Consider a target that is in s1. If a bombs are dropped, what is the probability

that it will transition to S3? There are three possible results of this action:

" Case 1: At least one of the a bombs provided a possible transition to a state

greater than S3.

If this situation occurs, the target will not transition to S3,

no matter what possible transitions the other bombs provide, but will instead

transition to the higher state.

" Case 2: All a bombs provide possible transitions to lower states. Once again,

if this situation occurs, the target will not transition to S3, but will transition

to the maximum state dictated by the possible transitions.

" Case 3: Neither of the above cases occurs. This is the only situation in which

the target transitions to state s3.

The extended damage model is generalized as follows.

target transitions from state i to state

j

The probability that a

given action a is:

T(si, a, sj) = 1 - Pr(Case 1) - Pr(Case 2).

(3.1)

The probability of Case 1 is the sum of the transition probabilities for state si to all

states higher than sj for action a:

Is'

Pr(Case 1) =

T(si, a, 5m).

)

(3.2)

m=j+1

The probability of a single bomb triggering case 2 is the sum of the transition probabilities for state si to all states lower than sj for a = 1:

j-1

T(si, 1, Sk),

Pr(Case 21a = 1) =

(3.3)

k=1

where T(si,

1, sk)

is given in T. The generalized form of equation 3.3 is the probability

38

that all a bombs dropped transition to a state less than sj:

Pr(Case 2)

r ZT(si, 1,

sk)

(3.4)

_k=1I

Finally, the probability that Case 3 occurs, that a target transitions from si to sj

given action a is a combination of equations 3.1, 3.2, and 3.4:

-1

T(si, a, sj) = 1 -

Is

-a

1 T(si, 1, s)

-

E

T(s a, SM).

(3.5)

m=j+1

-k=1

Since equation 3.5 depends on previously calculated transition probabilities for Case

1, the damage model must be calculated using dynamic programming, starting at the

highest state. Thus, T(sj, a, sisI) must be solved first for a given a, then T(si, a, sIS_11),

and so on.

3.1.3

Multiple Target Types

Any realistic battle scenario will include targets of different types, each with its own

S, T, R, and A.

Each of these target types has an associated MDP. Each one of

these independent MDPs is solved using value iteration, and the optimal values and

actions are stored separately from other target types'.

In the resource allocation

phase, each target will have its target type MDP checked for marginal rewards and

optimal actions. Multiple MDPs now need to be solved to allow for multiple target

types.

3.2

Implementation

The following sections describe how the problem solution method described in Meuleau

et al.'s paper was designed, implemented, and updated.

39

Resource

Affoottion

SOrrsponding

actionsA

poiy

Data

Actions

World

Simulator

SAl- ions

Structures

~s~ Atgcthm

States

'ndexes

Offline

Dynamic

Programming

Target

File

World

W

File

Figure 3-3: The completely observable implementation architecture

40

3.2.1

Architecture

The architecture for the problem solution method is identical to the one discussed in

section 2.3.1. Specific to the implementation, however, are the input files and data

structures, which can be seen in relation to the entire architecture in figure 3-3. The

input files are translated into data structures and used by both the offline and online

parts of the implementation.

The offline calculation loads in the target and world files (1) and produces an

MDP solution data file for every target type (2). Next, the greedy algorithm loads in

the target and world files (3), then begins a loop (4) in which it calculates the optimal

allocation for each target. To do this, for each target i, the greedy algorithm looks

up a value in the data structures, using a state s, a time step t, and an allocation

m.A

as an index. The greedy algorithm uses these values to create a vector of target

allocations, which get passed to the policy mapper (5). For each target, the policy

mapper uses the target's state, time index, and recently calculated allocation to get

an optimal action (6). After calculating the best action for each target, the resource

allocation phase passes a vector of actions to the simulator (7). The simulator takes

in the actions for each target and outputs the new states for each target back to the

resource allocation phase (8), and the online loop (4 - 8) repeats until the final time

step is reached.

3.2.2

Modelling

The entire description of a battle scenario to be solved by this technique can be found

in the information in two data input types: a target file and a world file. All data

extracted from these files will be used in the online and offline portions of the model.

Target Files

The target file defines the costs, states, and probabilities associated with a given

target type. A sample target file is shown in figure 3-4.

The first element defined in a target file is the state set. Following the %states

41

%states

Undamaged

Damaged

%cost

1

%rewards

0 100

0 0

transProbs

.8 .2

0 1

%end

Figure 3-4: A sample target file

separator, every line is used to describe a different state. The order of the states is

significant, as the first state listed will be so, the second si, and so on.

After the states, the %cost separator is used to indicate that the next line will

contain the cost for dropping one bomb. This is actually a cost multiplier, as dropping

more than one bomb is just the number of bombs multiplied by this cost.

The %rewards separator is next, and this marks the beginning of the reward

matrix. The matrix size must be ISI x ISI, where ISI is the number of states that

were listed previously. The matrix value at (i, j) represents the reward obtained from

a transition from si to sj. Note that in this problem, it is assumed that targets never

transition from a more damaged state to a less damaged state, and so a default reward

value of zero is used. This makes the reward matrices upper triangular.

However,

this model allows for negative (or positive, if so desired) rewards for a "backward"

transition, as may occur when targets are repairable.

The transition matrix is defined next using the separator %transProbs.This is

another ISI x ISI matrix, as before, where the value at index (i, j) represents the

42

Target

tb

te

A

B

C

D

E

F

3

1

14

15

3

7

12

5

23

20

21

12

Table 3.2: Sample beginning and ending times of targets

probability of a transition from si to sj if one bomb is dropped. The sum of a row of

probabilities must equal 1. Note that once again, for the definition of the problem in

this research, there are no "backward" transitions, so this matrix is upper triangular.

This model also allows for targets transitioning from a higher damage state to a lower

one. The probability for a transition from si to sj given an action of dropping more

than one bomb is given according to the previously defined damage model. The file

is terminated with the %eind separator.

World Files

The world file defines the time horizon, the resources, and the type, horizon, and

state of each individual target. A sample world file is shown in figure 3-5.

The first definition in a world file is the time horizon, as indicated by the %horizon

separator, followed by an integer representing the total "mission" time horizon. When

a scenario is defined by a world file as having a horizon H, the scenario is divided

into H + 1 time steps, from 0 to H.

The next definition is the total available resources, as indicated by the %resources

separator, followed by an integer representing Al.

This is the total resource constraint

for the mission.

After the resources, the %targets separator is listed. After that, there are one or

more four-element sets. Each of these sets represent a target in the scenario. The first

of the four elements is the target's begin horizon, tb which ranges from 0 to H - 1.

This is when the target comes into "view". The next element is the end horizon, te,

which ranges from tb + 1 to H. Table 3.2 lists several targets with various individual

43

%horizon

25

%resources

50

%targets

3

12

Meuleau

Undamaged

1

5

Meuleau

Undamaged

14

23

Meuleau

Undamaged

15

20

Meuleau

Undamaged

3

21

Meuleau

Undamaged

7

12

Meuleau

Undamaged

%end

Figure 3-5: A sample world file

44

t--

F -- 1

E

D H--C

-

H- B -- i

H

0

-5

A

I

10

15

20

25

Figure 3-6: Timeline of sample targets

horizons. Figure 3-6 depicts these targets graphically on a timeline of H

25. On

this timeline, at any current time step, te, any target whose individual window ends

at or is strictly to the left of t, has already passed through the scenario and will

not return. Any target whose individual window begins at or exists during t, is in

view, and is available for attacking. Any target whose individual window is strictly

to the right of t, will be available in the future for attacking, but cannot be attacked

immediately.

The third element is the target type. This is a pointer to a target type, so a

target file of the same name must exist. The fourth element is the starting state of

the target. The starting state must be a valid state. Currently, upon initialization,

the application checks for a valid state then ignores this value. targets are defined to

start in the first state listed, however, the flexibility exists in this implementation to

start in different states. At the end of every four-element set, the world file is checked

for the %end separator, which signifies the end of the file.

Generating world files is accomplished through interaction with the user. Users

are queried for the scenario parameters: a total allocation M, a time horizon H, the

number of targets N, the number of types of targets, Y, and the target type names.

Then it creates a world file with the appropriate M and H, and N targets, each

of which will be one of the entered target types with probability 1/Y. In addition,

the targets will be given windows with random begin and end times within the time

horizon.

45

3.2.3

Offline-MDP Calculation

Each target has been defined to have a reward matrix, transition probabilities, states,

and so on. Thus, different targets will have different value structures. The purpose

of the offline calculations is to solve an MDP for each target type, which, given an

state, a time horizon, and an allocation, returns an expected value and an optimal

action associated with the value. The problem as defined in this thesis has a finite

time horizon, and the following value iteration equation applies for each target, i:

Vi(si, t, m) = max 1 T(si, a, s') [Ri(si, s') + Vi (s', t + 1, m - a)] - cia

(3.6)

a<m sesi

This equation computes the value of the target i as the probabilistically weighted

sum of the immediate reward for a transition to a new state s' and the value for being

in state s' in the next time step, with a fewer bombs allocated, minus the total cost

of dropping a bombs. This value is maximized over an action of dropping 0 to m

bombs. Each maximized value V (si, t, m) will have an associated optimal action, a.

Equation 3.6 is solved by beginning in the final time step, t = H. The values for

Vi(s', H, m - a) are zero, since there is no expected reward for being in the final time

step, regardless of allocation or state. Thus the values of V at t = H - 1 can be

calculated, then used to calculate the values of V at H - 2, and so on, until t = 0.

The solution is stored as value and action pairs indexed by allocation, time, and

state. A sample data file for a two-state target with a horizon of 15 and an allocation

of 10 is shown in figure 3-7.

3.2.4

Online-Resource Allocation and Simulation

The resource allocation algorithm used in this research is a greedy algorithm. This

algorithm begins by assigning all targets 0 bombs. Then for each target, it calculates

the marginal reward for adding one bomb to the target's allocation. It does this by

looking up the value in the offline results corresponding to that target's time index t,

46

STATE 0

TIME 0

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

TIME 1

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

TIME 15

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

STATE 1

TIME 0

ALLOCATION

ALLOCATION

0.0, a = 0

0:

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

=

0:

1:

V

V

=

0.0, a = 0

=

18.999999999999996, a = 0

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

V

V

V

V

0:

1:

2:

3:

4:

5:

6:

7:

8:

9:

10:

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

V

0:

1:

V = 0.0,

18.999999999999996, a = 0

= 34.199999999999996, a = 0

= 46.359999999999999, a = 0

= 56.087999999999994, a = 0

= 63.870399999999989, a = 0

= 70.096319999999992, a = 0

= 75.077055999999999, a = 0

= 79.061644799999996, a = 0

= 82.249315839999994, a = 0

V = 84.799452672000001, a = 0

=

67.785599999999988, a = 6

= 72.028479999999988, a = 7

= 75.22278399999999, a = 8

= 77.578227199999986, a = 9

V = 77.578227199999986, a = 9

=

0.0,

0.0,

= 0.0,

= 0.0,

= 0.0,

=

=

= 0.0,

=

0.0,

= 0.0,

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

= 0.0,

V = 0.0,

V = 0.0, a

V = 0.0,

= 0

= 0

= 0

= 0

= 0

= 0

= 0

= 0

= 0

= 0

=

0

a = 0

a = 0

Figure 3-7: A sample data file

47

state s, and m =1 allocation. It then subtracts the offline results value corresponding

to that target's t, s, and m = 0. This is the marginal reward for changing a target's

allocation from 0 bombs to 1 bomb.

Once all targets have had their marginal rewards calculated, the greedy algorithm

allocates a bomb to the target with the maximum marginal reward. It then calculates

the marginal reward for adding another bomb to that target. If there is another bomb

left, the target with the maximum marginal reward is allocated a bomb, and so on

until either all bombs are allocated or the marginal reward for all bombs is 0. The

marginal rewards for target i are calculated according to the following equation:

A

(Sim, t) = Vj(si, m + 1, t) - Vj(si, m, t)

(3.7)

Thus, given a state si, a time step t, and an allocation rn, the marginal reward equals

the difference between the expected reward at the current allocation and the expected

reward at the current allocation plus one bomb. The Vi(si, m, t) and VK(si, m + 1, t)

values are retrieved from the data calculated in the offline phase.

After this greedy algorithm is complete, each target will have a certain number

of bombs allocated to it. In the data structures calculated in the offline phase, the

actions are paired with a set of a time index, a state, and an allocation. Thus, given

each target's t, s, and recently calculated m, the optimal action a is determined

directly from the data structures and put into a vector of actions for the first time

step.

This vector is now passed to the simulator, and the sum of these bombing

actions are subtracted from the remaining bombs left.

The simulator takes these

actions and, based on the probabilities calculated in the damage model, assigns a

new state s' E S to each target i, then returns a vector of these new states.

After this is done once, the resource allocation algorithm runs for the next time

step, but this time the total available weapons counter is decreased by the sum of

actions from the previous step and the target states are updated. This loop continues

until the time step is equal to H.

One problem lies in calculating the valid t for equation 3.7. Each target exists

48

in an individual window, but the application only knows

tb

and t, for each target,

and the current time step, t. What value should be used to index the offline values?

There are three cases.

Target window type 1 is the simplest, corresponding to te < t, for the target. In

this case, the target already "existed", and now has disappeared. This could be if it

was a moving target and it has moved into and out of range. The marginal reward

is zero for this target, as it will never be possible to damage it again. The greedy

algorithm will not even consider these targets, since there is no benefit to allocating

a bomb to them, and the actions associated with these targets will be to drop zero

bombs.

Target window type 2 is if tb

t, < t,. In this case, the target exists, as the time

step falls in the target's individual window. In this case, the t value used is equal to

H - (te - tc). To understand this, it is important to remember that Vi is calculated

from the final time step. t, - t, corresponds to the number of time steps left before

the target's window closes. Thus, since the values in the data files were calculated

for a target whose window was of length H, the proper value for t is the value for the

same target type with the same number of time steps left in the window. Section 3.3.1

discusses the optimization implications of this implementation.

Target window type 3 is when t, < tb. In this case, the target has not "come into

view" yet. This could happen if a target is moving towards the attackers. It would

be very bad to do the same thing as in case 1, since no bombs would get allocated to

the target. For example, say this target has a reward of destruction of 1,000,000 and

another target, which is of type 2, has a reward of 10. If there is only one bomb, using

the naYve "type 3 = type 1" method, the greedy algorithm would allocate that bomb

to the type 2 target. Then it may drop that bomb, and not have any to allocate to

this target. To avoid this problem, it is noted that for a fixed s and m, as t decreases

in equation 3.6, the values are nondecreasing. This corresponds to the idea that it is

worth more to have the same allocation in the same state if there is more time left

in the target's window. Thus the time index for a type 3 target is t = H - te, or the

total horizon minus the end time. The action, however, for a type 3 target is always

49

Action dependent on

MDP solution

Action =0

Target considered

Targetnsidred

.for

alUocation

for allocation

Action =0

T5rget NOT

coidred for

for allotin

..I

Type 2

Type 3

Target

0

tb

tH

Figure 3-8: A timeline depicting the three types of target windows

drop zero bombs, since the target "does not exist" in the current time step, and all

bombs would by definition miss.

Figure 3-8 shows the progression of the types of a target over a horizon. The

target "exists" in the white part of the figure, when it is type 2. In this section,

the target is considered for the allocation of bombs, and its action is dependent on

the offline values. In the left grey area, the target does not exist yet, but will in the

future. The target is still significant to the problem as type 3, as it still needs to be

considered for weapon allocation. However, since the target does not exist yet, the

action for a type 3 target will always be to drop 0 bombs. Conversely, a type 1 target

in the right gray area no longer needs to be considered for weapon allocation. Again,

since the target does not exist, the action will always be to drop 0 bombs. For the

boundary cases, at tb and te, the target changes to the next class, as is shown in the

figure.

Determining the target indexes for the target types is simple. All target indexes

begin at t = H - te, and every time step, the index is incremented by one. When

t = H, the target window has passed, and the target is effectively removed from

resource allocation consideration.

50

3.3

Implementation Optimization

The first version of the totally observable resource allocation method took a great

deal of time to calculate the offline values. Optimization did not seem to be a luxury,

but rather a necessity to make the problem more tractable. It is possible to decrease

the total amount of calculation by exploiting certain aspects of the MDP.

3.3.1

Reducing the Number of MDPs Calculated

As mentioned in section 3.2.4, the value of two different targets of the same target

type is the same if they have the same time index, meaning only one MDP calculation

is required for each target type. At first, one MDP was calculated for each target.

This took a great deal of time and computation.

However, since the only thing

that changes for calculation of 1V between these MDPs is the t in equation 3.6, the

calculations were duplicated. However, the calculations need only be done once, for

a maximum horizon, H. Once the maximum horizon MDP has been calculated, the

online phase just needs to select t properly. Making this change reduced the number

of MDPs from the number of targets to the number of target types. Though this

does increase the size of the MDPs, in most realistic world scenarios, the increase

in computation caused by the increased number of time steps is much less than the

computation time to calculate an MDP for every target.

It would be possible to only calculate the MDP for the maximum target horizon

and then use those MDP values in the online phase. This actually optimizes the

solution method for one scenario. But a large horizon can be selected for compatibility

with future scenarios. If a horizon of 100 is calculated, then any problem with a