The Timeliness Project Background Report

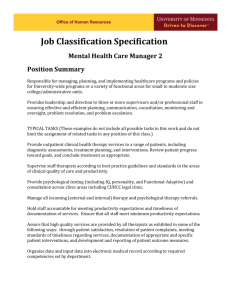

advertisement