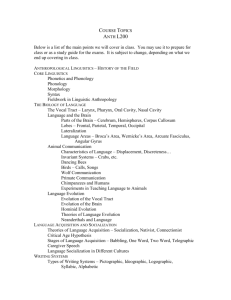

Paper Methodological foundations in linguistic ethnography

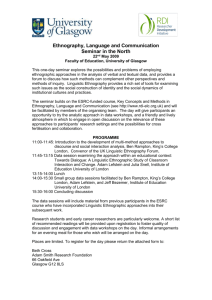

advertisement