Paper From fieldnotes to grammar Artefactual ideologies of language

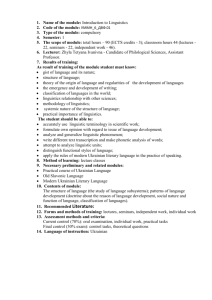

advertisement