Paper The aesthetics of microblogging: How the Chinese state controls Weibo

advertisement

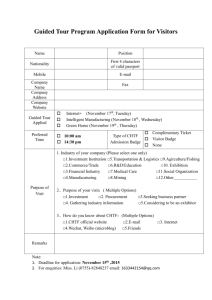

Paper The aesthetics of microblogging: How the Chinese state controls Weibo by Jonathan Benney © (University of Oklahoma) jbenney@gmail.com © July 2013 The aesthetics of microblogging: How the Chinese state controls Weibo Jonathan Benney, University of Oklahoma1 Key words: Weibo, microblogging, interface aesthetics, human-computer interaction, China Biography: Jonathan Benney is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Oklahoma’s Institute for USChina Issues. His research interests are centred on social activism, political communication, and the use for political purposes of new media in contemporary China. His first book, Defending Rights in Contemporary China, was published by Routledge in 2013. He has a doctorate from the University of Melbourne, and has most recently worked as a research fellow at the Asia Research Institute at the National University of Singapore, and as a visiting fellow at the Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany. Author email: jbenney@gmail.com Mailing address: Institute for U.S.-China Issues, University of Oklahoma, 338 Cate Center Dr., Norman OK 73019, USA Abstract: Microblogs, epitomized by Twitter in the West and Weibo in China, have attracted considerable attention over the past few years. There have been a number of optimistic accounts about their potential to stimulate political activism and social change, juxtaposed with suggestions that their networks are too weak and that they are too easily censored for such change to occur. Yet in this debate, little attention has been paid to the medium itself; microblogs have too often been treated as mere conduits for information, and the practical and aesthetic experience of microblogging has been marginalised. This article addresses this imbalance in two ways. First, it argues that the microblog is a distinctive medium with special potential for political communication. It applies Rancière's “politics of aesthetics” and Baudrillard's “private telematics” to microblogs, suggesting that the particularly immersive quality of microblogs provide new and distinct opportunities for the promotion of opinions and social movements. Second, it argues that by allowing, remodelling, monitoring and censoring the Weibo service, the Chinese party-state is deliberately manipulating the medium of the microblog to reduce the risk of activism, controversial use, and network formation. Thus, the medium of Weibo differs from Twitter in several important ways, each of which, the article argues, are intended to maximise the cacophonous spectacle of entertainment and to minimise reasoned discussion and debate. Furthermore, while pure censorship of information can be evaded in many ways, it is more difficult for dissenters to evade state control when it is applied to the medium itself. ================== 1 In a much earlier form, this paper was originally presented to the Asia’s Civil Spheres: New Media, Urban Public Space, Social Movements conference, held at the National University of Singapore in September 2011. I offer my sincere thanks to Tripta Chandola and Peter Marolt, together with two anonymous referees, for their comments on drafts of this paper. 1 Implicit in the term “media” — and even more in “new media” — is the suggestion that the world of communication is composed of various different means of presenting information, each its own “medium”. What distinguishes one medium from another are qualities which can largely be described as aesthetic: matters of design, organization, styles of language, and so on. These aesthetic factors are inherently visible to those people who work in the practical and technical side of each medium — web designers, camera operators, or radio technicians, to give a few examples — but for academics in the social sciences, one substantial risk is to regard the media as mere conduits for information, and to ignore the aesthetic and technical aspects of the presentation of data. In the study of microblogs (those websites such as Twitter (twitter.com) in the West and Sina Weibo (weibo.com) in China, which allow users to make 140-character posts), this problem is especially acute, particularly in terms of political communication and debate. On current trends it is possible that one billion people will have microblog accounts in a few years2, but little attention has been paid to the aesthetic reasons for the growth of the medium, or the ways in which the design and use of microblogs differs from place to place. Previous scholarship on the microblog has largely taken two forms: analyses of the growth of the medium and its response to particular events (Java et al, 2007; Hughes and Palen, 2010; Brown et al, 2011; Bruns and Burgess, 2011; Wayant et al, 2012), and teleological debates which argue about the potential of microblogs to effect substantive political outcomes (Morozov, 2011; Benney, 2011; Sullivan, 2011). Comparisons of Twitter and Sina Weibo (Chen et al, 2011; Gao et al, 2012) have largely been technical in focus. Overall, I would suggest, the work on microblogs, and Sina Weibo in particular, has been characterized by an over-emphasis on flows of data (that is, how individual posts travel across the microblog network, and who views them), specific events (how people use microblogs in response to controversies or disasters), and hypothetical outcomes (whether the use of microblogs has the potential to effect political or social change). It has consequently marginalized questions of design and aesthetics, of human-computer interaction, and of the role of the state. In the case of China, where the state devotes particular effort to surveillance and control of the Internet, and where a distinctive Internet aesthetic has developed, this is an especially serious omission. In this article, I address this problem by demonstrating that the Chinese party-state has manipulated the medium of Weibo, at an aesthetic level, to stifle political communication and, at a broader level, dissent and activism. In making this argument I draw particularly from three conceptual sources: Jacques Rancière’s “politics of aesthetics”, the technical field of human-computer interaction, and the nascent field of interface aesthetics. The empirical argument that this aesthetic manipulation has been facilitated by the state is made first by illustrating the clientelist relationship between the Sina Corporation, which operates Sina Weibo, and the state, and second by demonstrating the differences in design and operation between Sina Weibo and other microblogs, in particular Twitter. 2 In late 2012, Twitter claims over 500 million registered users (O’Carroll, 2012), while Sina Weibo claims over 400 million (Ong, 2012). Collectively, in 2011, the Sina and Tencent Weibo services claimed over 550 million (Russell, 2011). It is likely, therefore, that the one billion mark will be passed sooner rather than later, if it has not already been passed. However, it is important to distinguish accounts from actual users. Vast numbers of these registered accounts, however, may be so-called “zombies”, registered en masse by spammers or sold to users to inflate their numbers of followers. Fu and Chau (2013) discuss this further. 2 How do Internet aesthetics work in China? The Chinese Internet has two obvious special characteristics: first, it has greater than normal state control (both in terms of censorship and the relatively close links between state and market), and second, almost uniquely, it uses a language based wholly on characters with little or no alphabetic element. These, plus a range of historical and practical factors, have shaped the aesthetic appearance of the Chinese Internet. Attempts to characterize this particular aesthetic, however, have been limited. Common Western critiques of Chinese websites suggest that they are visually unappealing, unnecessarily complex, full of hyperlinks and text, crude, garish, and “busy” in their design, and difficult to navigate (backboneitgroup,com, 2011; teamtreehouse.com, 2011; Tan, 2011). Figure 1, below, demonstrates how this tendency can be seen in the popular portal website 163.com. Less judgmental analyses characterize the Chinese Internet as having an “aesthetics of abundance” and a relatively “flat” hierarchy of information, leading to masses of complicated information being placed on single pages (Ess, 2007, p. 186). But, other than from the world of web design and marketing, attempts to describe the nexus between the appearance of the Chinese Internet and its full range of functions are almost impossible to find. Figure 1: 163.com front page, accessed 10 July 2013. For the purposes of this article I concentrate on the links between Internet aesthetics, particularly in China, and political communication. In particular, I rely on Jacques Rancière’s framework for understanding politics, aesthetics, and social change. Rancière defines “politics” as forms of intervention into a “distribution of the sensible” (that is, the way in which acceptable forms of public discourse are distinguished from unacceptable forms) by those who are normally outside of or excluded from the community (Rockhill, 2004, p. 3). Politics, then, is framed as a struggle for control of what is “sayable”, where “equality” (between all members of the community) sporadically reappears through disturbances in the set systems of social inequalities. 3 In Rancière’s analysis, such interventions are closely linked to matters of aesthetics: to him, the modern historical narrative has been deeply shaped and influenced by the development of new forms of art and literature, each of which has disturbed the sensible by framing ideas in novel ways (Rancière, 2004, pp. 32-33). As Benjamin Bratton has put it, the existence of a new way of arranging data “asks how it is that we may sense the world, or how the sensibility of the world might be distributed… or organized, instrumentalized, and activated to become a part of the way the commons understands and narrates itself. It is not only an image… it is a tool for a politics that doesn’t yet exist. “ (Bratton and Jeremijenko, 2009, p. 36) In studying the Chinese Internet, Rancière’s emphasis on conflicts and interventions as the core of politics is especially fruitful, first because it acknowledges the size and complexity of China and its Internet, and second because it complements the more frequently used ideas of state surveillance of the Internet: that is, the Foucauldian “technologies of control” discussed, for example, by Xiao (2011). Rancière himself suggests that his work is phrased “in terms of internal division and transgression”, in contrast to the emphasis of Foucault (and therefore of much of the previous academic analysis of censorship on the Chinese Internet) on “limits, closure and exclusion” (Rancière et al, 2000, p.13). This approach allows us to come to terms with a paradox of the Chinese Internet: that it is both very free and diverse and very highly policed. As I indicate below, Rancière’s analytical framework is borne out by the use of state strategies which use strategies of aesthetics as well as surveillance. In Rancière’s terms, then, the political possibility of a new aesthetic form (in this case, microblogs in China) is that it might challenge the normal distribution of the sensible (thus “doing” politics), facilitate equality (speaking for the “people”, those normally “invisible and inaudible”), and disturb the “organizational system” (what Rancière calls the “police”). This provokes two questions. First, how do aesthetic practices work on the Chinese Internet, and specifically in the case of Weibo? Second, given the high level of state involvement, what means do the Chinese “police” use to control Internet aesthetics? Questions of aesthetics, design, and human-computer interaction on the Chinese Internet have been discussed largely through two frameworks. The first framework is technical and pragmatic, suggesting that the aesthetic choices made by the designers of Internet systems are based on limited design expertise and minimal resources (Wang, 2003; Tan, 2011), a claim often used to rebut the suggestion that Chinese Internet aesthetics are ugly or confusing (backboneitgroup.com, 2010). The second method relies on the “cultural dimensional” approach adopted by Hall and Hall (1990) and Hofstede (1980). This method of analysis posits various characteristics which it is asserted can be applied to China as a whole, and suggests that these characteristics are either visible in Chinese information systems, or that they should be used in designing Chinese user interfaces (Würtz, 2005; Hsu, 2007, p. 276). On the whole, both of these explanations are insufficient. This is first because the aesthetic and cultural qualities which are deemed to be important to Internet design tend to be arbitrary: Chui Chui Tan (2011) for example, suggests that the Chinese concept of “face” means that web designers want to cram large amounts of information onto single pages, and that, as “China is an expressive society”, icons and animation are common. Both the suggestion that “face” and “expressiveness” are key to Chinese society, and the idea that these qualities would naturally be expressed through long pages and icons, are essentialist and poorly reasoned. But even more importantly, the existing discussion of Chinese Internet aesthetics marginalizes the state. In tandem with Rancière’s work, the field of interface aesthetics 4 (pioneered by Berthelsen and Pold (2004) and Andersen and Pold (2010)) brings the idea of the hegemon back into analysis of Chinese Internet design. Arns (2010) suggests that the quality of “transparency”, a frequent aim of interface designers in the sense that the aesthetic qualities of the interface are not consciously perceived or detected by the user, is closely linked with “control societies” which aim to survey and monitor the acts of their subjects without this surveillance being visible: “The age of transparency is marked by a dual structure of the panoptical and post-optical.” (Arns, 2010, p. 260) This idea runs in parallel with Hoofd’s argument that a “speed-elite” is using certain aesthetic qualities of online communication to stifle activist debate (Hoofd, 2012), and, furthermore, with the overwhelming empirical fact that, at a macro-level, large corporate bodies and states exercise high levels of control over communications networks (Arns, 2010, pp. 264-267). What I propose to do in the sections below, then, is to identify certain “transparent” features of the microblog interface — qualities which can be described both as aesthetic features and as features of the human-computer interface — which I suggest have been manipulated by the Chinese party-state as a means of exercising forms of social control which are intended to maximize loyalty to state ideologies and minimize dissent. One part of my reasoning relates to ways in which Sina Weibo differs from Twitter, the original microblog; comparisons with Twitter are the most useful way of highlighting the relevant differences of Sina Weibo. Such comparisons are not intended to suggest that Twitter is free of state influence, of political motivations, or of commercial avarice. The evidence suggests that it is not. However, below I suggest that — in relative terms — Twitter has developed on internationalized lines and has been responsive to its users as well as to corporations and the state. Sina Weibo cannot be said to have done these. Sina Weibo as a state-approved microblog Before performing an analysis of the microblog interface, it is important to establish clearly that Sina Weibo, and consequently its interface design, have close links with the Chinese party-state. This can be done in a number of ways. First, it is clear that non-approved microblogs are routinely censored. Although Twitter was occasionally unavailable in China before 2009, it was only after large-scale riots in Xinjiang in mid-2009 that the site was permanently blocked (Wauters, 2009; Bamman et al, 2012). By 2010, individuals using Twitter were being targeted and detained on the basis of posts they had made (Shahid, 2010). However, other native Chinese microblog services, such as Fanfou and Digu, were also being censored at the same time. Sina Weibo appeared on the Chinese Internet after a large-scale purge of all other microblog services (Millward, 2009), which would strongly suggest that the site was designed from the outset with relatively close links to the party-state and its apparatus of censorship. Second, the fact that Sina Weibo is a subsidiary of the Sina Corporation indicates the relative likelihood that it enjoys the structural and corporatist support of the party-state. The Sina Corporation is very large and economically significant: it runs the Sina web portal, which is one of the most popular websites in China, and operates a range of blogs, news services, and so on. Furthermore, it has long been suggested that Sina, and its predecessors the Stone group of companies, has enjoyed a clientelist relationship with the state, characterized by close personal relationships between the management of the company and state officials and preferential treatment (Kennedy, 1997; Hu, 2002). Other microblog clones such as Fanfou have been far less able to harness the support of the state and of corporate finance. Although the state and Sina have therefore generally had a cooperative relationship, Chin and Chow 5 (2011) describe the tightrope that Sina must walk to ensure that their service remains acceptable to the state and thus practically viable. Symbolic visits to the Sina headquarters from Communist Party chiefs serve to “promote healthy growth of the Internet” from the party-state’s point of view, and, more realistically, act to put pressure on Sina to maintain its diligence in censorship. Lagerkvist (2012) contextualizes this further, describing the “cadre-capitalist alliance” prevalent in large social media companies. Sina Corporation, for example, has played an active role in liaising and communicating with government, as its facilitation of conferences relating to state participation on microblogs demonstrates (Lagerkvist, 2012, p. 2640). It should be acknowledged that the need for Internet companies to provide entertainment, to make profits, and to manage the desire of the public to communicate freely, also sets up contrasting imperatives: to free speech, to support anonymity, and not to facilitate censorship. The challenge of “serving two masters [the party-state and the public] with diverging interests” (Lagerkvist, 2012, p. 2629) has indeed affected decision-making in Chinese Internet companies. But at a higher managerial level, where questions of design and aesthetics are ultimately planned and approved, liberal attitudes to free speech are less common, and cooperation with the state is the norm (Lagerkvist, 2012, p. 2636). Third, substantially as a consequence of this “cadre-capitalist alliance”, it is clear that debate about Sina Weibo and its content is regarded by the party-state as an acceptable subject for public discussion. The state media treat Sina Weibo (as distinct from Twitter or other discredited types of microblog) as an interesting topic for discussion and as a valid conduit for information, albeit one with many perceived risks. Official media have trumpeted the setup of Weibo accounts by government departments as demonstrating increased responsiveness of local officials to citizens’ concerns. Zhang and Jia (2011) and Liu (2012) demonstrate the level of cooperation between the Sina Corporation and government in this respect. Recently it was claimed (in a news article promulgated on the Sina portal) that an examination for government officials in a county in Zhejiang province required candidates to write Weibo-length posts promoting particular initiatives (sina.com.cn, 2012; Yu, 2012). Overall, then, any suggestion that Sina Weibo is providing an outlet for dissent, activism, or critical forms of political communication (as Chander (2012) and Shank and Wasserstrom (2012), to provide just two of a plethora of recent examples, suggest) must be balanced against the evidence which indicates that the Sina Weibo service has specifically been set up as a state-approved service with clientelist characteristics, which is intended approximately to serve as a monopoly for the medium of microblogging. The process of microblog censorship as described by Bamman et al (2012), involving the identification of “sensitive words”, the deletion of posts, and, as I discuss below, the selective removal of the comment feature, should also be understood as something that is being performed by Sina in cooperation with the party-state and not as a reactive process which the corporation is being forced into. Under these circumstances, it is more realistic to parse dissent and censorship on Weibo, as Hassid (2012) suggests, as being a “safety valve”, allowing citizens to voice their anger at particular problems, rather than signifying the formation of substantial anti-authoritarian movements, or, similarly, as being part of the state’s agenda-setting process which aims to “guide public opinion” (yulun daoxiang) by identifying acceptable topics for debate and circumscribing acceptable boundaries for the expression of heterodox opinion (Chan, 2007). Of course not every piece of information that individuals publish on Sina Weibo is acceptable to the state, but it is important to note that the Sina Weibo service is the microblog service 6 used by the vast majority of Chinese users and that all its characteristics have been closely monitored and effectively approved by the state. Therefore, as I suggest in the next section, the differences between Sina Weibo and its predecessors and competitors (chiefly Twitter) can be used to illustrate the attitudes of the state towards information and online dissent. Methodologically speaking, such a comparison must be aesthetic in nature: primarily qualitative, with quantitative analysis used only as reinforcement. The differences in design are differences of degree; however, as I argue below, these differences of degree can lead to quantitatively different outcomes of use. The potential benefits of the microblog medium to public discourse In a previous article (Benney, 2011) I argued that microblogs (in this particular case, Twitter as used by Chinese legal activists) had a positive effect on activism and legal discourse in China, partly because of the formation of communication networks and partly because of characteristics of the Twitter medium itself. The fields of human-computer interaction and interface aesthetics allow us to develop this analysis further. There are a number of ways of conceptualizing the specialness of the microblog medium. Brenda K. Lauren (1984), for example, was one of the earliest writers to articulate the idea that the computer interface can be a mimetic medium, and one which can engage the user in a first-person immersive experience, where the user is effectively the protagonist in a form of performance. In the intervening years, much has been written about virtual spaces and immersiveness, but frequently these writings have skirted one of Lauren’s original ideas: that the metaphor of the first-person mimetic performance can apply to interfaces which are not necessarily intended to replicate real spaces: the performances of which Lauren speaks may involve a library catalogue or file management interface as much as a computer game. The interface design, therefore, can do much to shape the way in which the user views themselves, their interactions with others, and the things they are supposed to do or to refrain from doing. To consider microblogs more specifically, Berg and Strafella (2012) have usefully applied Baudrillard's idea of “private telematics” to the user experience of Twitter: Each individual sees himself promoted to the controls of a hypothetical machine, isolated in a position of perfect sovereignty, at an infinite distance from his original universe; that is to say, in the same position as the astronaut in his bubble, existing in a state of weightlessness which compels the individual to remain in perpetual orbit flight and to maintain sufficient speed in zero gravity to avoid crashing into his planet of origin (Baudrillard, 1988, p. 15). This metaphor captures several important aspects of the microblog user experience. Chief amongst them is its solipsism: the priority it places on the individual as observer, placed above a world of her or his own construction. Second is the emphasis placed on the flow of information ― what Berg and Strafella call a “sustained communicative feed”. The crucial aspect of this flow is that it is continuous: a given speed must be maintained to avoid a crash. While the microblog flow is composed of small fragments of data, it is not the quality of each fragment that matters, but the overall immersive effect. Just as a computer image is decipherable even if some of its pixels are missing or erroneous, and just as Baudrillard's astronaut will be sustained by his momentum if there is a momentary loss of power, the most important factor for many microblog users is to sustain the flow and the speed of posts, rather than to engage deeply with the content of each post. 7 If we now turn specifically to the question of political communication on microblogs: on an empirical level, the research suggests that this continuous flow of information, selected and mediated by the individual user, tends to lead to an intensification of the user's existing beliefs. Habitually the user follows other users with whose beliefs they are already closely aligned: when they log onto a microblog and immerse themselves in the flow of posts from those they follow, much of the pleasure and comfort of the experience results from reinforcement of what they already know, or the reframing of new information in terms of their existing beliefs. Yardi and boyd (2010) characterize this as an online means of facilitating the offline social practice of homophily; Sunstein (2001) as the “Daily Me”. Therefore, notwithstanding Hoofd's arguments about the way in which these speed-based media limit the capacity for substantive debate, the microblog medium demonstrates an especial capacity to reinforce political ideologies and communities. Furthermore, in cases where these ideologies run contrary to the wishes of the state, microblogs are more difficult to censor because — commensurate with the emphasis on ongoing flow over substance and debate —individual followers can follow many separate sources of information, be they individuals or corporate bodies, and it is relatively easy for the producers of microblog posts to set up multiple accounts and produce new information from new sources when one account or source of information is suppressed. This, as I suggest below, is one key reason for the Chinese state's manipulation of the aesthetics of the microblog medium as well as its censorship of the flow of data: in theoretical terms, attention is effectively being paid to Rancière’s distribution of the sensible as well as Foucault’s panopticon. The brief and fragmented nature of microblog posts gives the medium other special characteristics. As I have previously argued, the simplicity and narrowness of the microblog post has led to users devising their own techniques to enhance the communicative capacity of the medium and interaction between users. For example, retweeting (reposting another user’s post, the equivalent of “forwarding” in Sina Weibo) was not one of the original functions integrated into Twitter (Benney, 2011, p. 10). Rather, a method of indicating retweeted posts (inserting “RT” at the start of a quoted post) was devised by Twitter users, and it was more than three years after this that Twitter incorporated a retweeting function into its basic functionality. The use of hashtags to label and collate posts of particular issues was, similarly, devised by users after once the Twitter medium had already been formulated: a technique described as a “diffusion of innovation” (Chang, 2010), or, even more tersely, as a “hack” (Santo, 2012, p. 3); it is the combination of simplicity, the necessity for brevity, and the absence of pre-programmed features which has facilitated the development of this type of “hacker literacy” or “hackability” of the medium and thus increased the communicative agency of microblog users. While Chinese users of Twitter have not necessarily devoted much time to “hacking” Twitter, they have exploited one particular loophole in its construction. Evidently drawn from the 160-character limit of SMS text messages, the 140-character limit to microblog messages uses the Unicode character encoding, which treats a single English letter as a “character” equivalent to a Chinese character. Since Chinese characters are roughly equivalent to English words, it is possible to communicate relatively more information in a Chinese microblog post than an English one. This has made the Chinese microblog sphere more discursively dense than the English, allowing for short essays to be written and for the contributions of several users to be included in a single post (Benney, 2011, pp. 8-10; Gao et al, 2012, p. 8). Expert users of Twitter in China have used this functionality to engage in relatively substantive debates about legal issues such as the death penalty (Benney, 2011, pp. 14-15), although this observation must be counterbalanced by noting that Twitter users in China are generally an 8 elite group, able to use circumvention devices to access the service, and with particular interest in politics and legal matters (Sullivan, 2012, p. 774; Lukoff, 2011). Coupled with the popularization of an informal anti-authoritarian argot (often collectively referred to under the name of its best-known symbol, the Grass Mud Horse (see Xiao, 2011)), and the high level of accessibility of the Weibo service (which can be used on mobile phones as well as computers), and of course the rapid increase in Internet access across China, the appeal of the microblog medium has been such that Weibo is popular across China and across different social sectors3 (Hassid 2012a), arguably, on a numerical level, more so than Twitter. While the transfer of pieces of information on Weibo has been studied in depth, the aesthetic qualities of the microblog medium — in particular the immersiveness and transparency of the Twitter experience, the constant flow of data, and the “hackability” of the medium — remain crucial to its success. Further, each of the factors described above militates against the risks described by Honeycutt and Herring (2009, pp. 1-3) who characterize Twitter as a “noisy” medium, because of its large volume of small pieces of content, not necessarily in a logical order, and “not especially conducive to conversation”. From Twitter to Weibo — the state’s distortion of the microblog As suggested above, the transfer of information on Weibo is closely monitored by the state. Lists of “sensitive words” (minganci) are kept: users cannot search for these words and posts containing them are deleted. When controversial events take place (to give one example, the 2012 scandals involving the politician Bo Xilai and his wife Gu Kailai), Weibo censors actively work to delete and suppress relevant posts, even as users modify their language in an attempt to avoid this. Bingchun Meng (2010 and 2011) characterizes this censorship, and indeed the development of the Chinese Internet as a whole, as a form of “mediation”: the idea is that the forms taken by the Chinese Internet are shaped by constant negotiations between users, service providers, and the state, each of which attempts to secure the flow of information most compatible with its interests. The concept of mediation allows us to question some of the teleological narratives relating to the Chinese Internet, in particular the suggestion that increased political communication will lead to democratization, or, alternatively, that state control over the Internet will lead to increased suppression of dissent. But, to draw again from interface aesthetics, if features of the online interface are transparent to the user yet affect their access to information and the way in which they interpret it, this cannot be said to be mediation. Rather, it is better regarded as being a new technology of state control. Manipulation of the aesthetics of Internet interfaces can be usefully labeled in the terms developed by Thalen and Sunstein (2008): as a form of engineering of users’ “choice architecture”. As an alternative to censoring information, the strategy is to design the environment so that the user is subconsciously inclined to choose to engage with information approved by the state, and disinclined to engage in controversies. In developing Sina Weibo, I suggest that the Chinese state has indeed taken this approach. The aesthetic aspects of Sina Weibo which differ from Twitter are not incidental or merely cosmetic, as some have suggested (see Tan, 2011). In fact, to regard the changes as cosmetic 3 Wallis (2012) points out the class differentials inherent in technology use in China: poorer and more rural citizens are far more likely not to use mobile technology or to use it mainly for simple interpersonal communication. Nonetheless, with the cost of smartphones and of Internet data rapidly decreasing, this trend is gradually becoming less meaningful. 9 merely underlines the idea that these differences are transparent to the user. Nor does the “culturalization” hypothesis mentioned above seem appropriate: there are insufficient features of the Weibo medium which align closely to any essentialized version of Chinese culture, and the practical reasons (lack of bandwidth and lack of design expertise) which are provided as reasons for the characteristic features of Chinese web design hardly apply to a text-based medium like the microblog, nor to an extremely large corporation like Sina. Below I classify the various aesthetic differences in Sina Weibo as compared to Twitter under three general headings: first, a concentration on consumption and entertainment; second, a relative emphasis on surveillance and identity; and third, a relative lack of "hackability" or user control over the interface. To consider consumption and entertainment first: Kraus (2004, p. 98) makes the argument that Chinese artists have collaborated with the state to develop a “bread and circus public culture” based more on sensational entertainment than on discursive discussion of serious issues, which is perceived to involve a risk to state stability. This analysis is congruent with the rise of China’s celebrity culture, wherein state and market have worked closely to facilitate the promotion and idolization of famous people in sports, entertainment, and so on (Jeffreys and Edwards, 2010, pp. 2-3). This basic paradigm for the promotion of modern Chinese culture appears to hold for Sina Weibo. Recent research conducted by HP Labs demonstrates that the most popular users (that is, with the most followers and those whose posts are most frequently reposted) fall into three groups: representatives of companies and brands (such as the fashion brand VANCL), updates on entertainment (such as magazines about fashion, travel, and music), and generalized sources of entertaining information (such as jokes, horoscopes, stories, and “beautiful pictures”). In contrast, of the top twenty popular Twitter users in China, more than ten were news services, including CNN, the New York Times, and the BBC World Service, all of which would routinely be censored in China. (Yu et al, 2011, p. 5). The ongoing public interest of a section of society in Twitter — and the regular outbreaks of comment on public issues on Sina Weibo — demonstrates that the entertainment orientation of Weibo is not entirely a question of market demand. It is also shaped by the way in which Weibo works as an information system. The design focus of Weibo is oriented towards consumption and entertainment, not merely because it is marginally more colorful and flashy than Twitter, and contains slightly more advertisements. For example, people who sign up for Sina Weibo must now select one or more “interests” before they can access the main page. Doing so forces one the user to follow (guanzhu) a particular set of verified Weibo users. Most of the “interests” are based on entertainment and consumerism (the media, sports, cars, food, and so on), and, even if one selects the “news” interest, one is made to follow celebrities, recipe sites, and the fashion media (in my case, the specialist handbag blogger “Bagsnob”, the “Dragonfruit Cooking Club”, and the actress Tang Yan) — with the chief sources of actual news being the People’s Daily and the Shanghai police news (that is, largescale official media). One can unfollow these accounts and search for users who are more relevant to one’s own individual interests, but the fact remains that, especially for beginner users, Weibo meets the eye more as a cornucopia of pseudo-advertising and a paean to the cults of celebrity and consumption, rather than as a means for individuals to express themselves and their opinions. New users of Twitter are now also pushed into following other accounts before they are properly registered4, but the new users are not forced into following 4 It is possible to circumvent these post-signup processes in various ways, both for Weibo and Twitter, but these means are entirely unobvious for the beginner user. 10 a particular set of accounts, and in fact can choose from a random list of accounts, partially chosen on the basis of the user’s geolocation and previous web history (in Singapore, one immediate suggestion was the famous anti-government blogger “Mr Brown”). Further, whereas Twitter remains relatively close to its roots as a purely textual service, the Sina Weibo medium relies much more heavily on the image. Linked images in Twitter posts are hidden from the viewer unless clicked on, whereas Weibo displays images automatically (as shown in Figure 2), making the crucial first-person flow of information one which relies on pictures as much as text. When a Weibo user makes a post, they have always been invited to attach images and videos and to include emoticons in their posts; Twitter includes fewer of these features and originally included none. Overall, the design of Weibo draws partly from the “lightweight blog” paradigm, best epitomized by Tumblr (Chen et al, 2011, p. 2262). This medium is characterized by a very high emphasis on the pure use of images and on the constant sharing of content through reposting (Wagner and Motta, 2009), a trend which can be observed more clearly in Weibo than in Twitter (Yu et al, 2011, p. 1). In terms of political communication, it can be observed that the emphasis on the image militates against the increased discursive capacity that the Chinese-language microblog theoretically allows for. This emphasis on state-approved consumption and on images, therefore, forms a strategy for suppressing political communication on Weibo, particular for newer users. Figure 2: The stream of Sina Weibo (accessed 10 July 2013). Many of the smaller emoticons are animated, and images are displayed inline. The blue “V” icon indicates a verified user. Second, surveillance and identity. Separate from the Chinese state’s surveillance over the Internet, users of Sina Weibo are forced into many more processes of gatekeeping and selfsurveillance than users of Twitter. Part of this involves the automated censorship of posts including various sensitive words, but the process of identity formation for the individual Weibo user also involves inculcating a greater sense of attachment to the Weibo medium and of individual vigilance about information. Signing up on Weibo requires that the user provide 11 more personal details than on Twitter (passport or identity card numbers, for example); individuals are requested to identify themselves with a school attended as well as a geographical location. Each of these factors leads to greater vigilance about what information the individual is willing to provide online, in that it is easier for the service provider to track them, but arguably these features are not transparent to the user. The Weibo interface, however, manipulates identity in other ways. First, it emphasizes the verification of information far more. Verified users (who on Weibo are marked with a “V” icon, yellow for individuals and blue for organizations, as shown in Figure 2) exist on both Twitter and Weibo; in both cases these users have communicated with the service provider to confirm their identity (see Chen and She, 2012), but on Weibo verified users are promoted far more, both in the sense that they are given priority on the website and that the fact that they are verified is promoted more heavily. Verification also allows Weibo users to gain access to special features of the service (such as the VIP service mentioned below). This ties in with the rhetoric of suspicion towards rumors and gossip, which has been used by the party-state and its supporters to call the authority of microblog users, particularly controversial users, into question (Yang, 2011; Bandurski, 2011); thus altering the ways in which users view the flow of data over Weibo, and affecting their decision-making. Second, the Weibo user interacts with the system’s interface in a far more elaborate way than the Twitter user does. To mention only a selection of the extra features: as in a role-playing game, each Weibo user is assigned a “level” (dengji) which increases as the user makes posts and befriends others on the site. One can duel with others (in a competition called “PK”) to see who is more popular, and play games which are integrated into the Weibo interface in the style of Facebook games. Similarly to the Nintendo Wii’s “Mii” avatar system, the user can create a “Wei Me” avatar who participates on their behalf in the games. By paying a ¥10 monthly fee, it is possible to upgrade one’s account to “VIP” status, upon which a golden crown icon appears by one’s account and one receives extra membership features. None of these features appear in Twitter in any form. 12 Figure 3: Weibo’s “PK” page (level.account.weibo.com, accessed 9 July 2013). The author (an infrequent poster on Weibo), is only at Level 2; other of his Weibo “fans” are at Level 8 and Level 12. Collectively, these interface factors have two effects. First, they frame the Weibo system as one which places greater emphasis on consumption, entertainment, and network formation than on discourse and discussion. Second, they ensure that the user spends more time engaging with the system itself than with the information it provides. Whereas both Twitter and Weibo provide the first-person immersive experiences characteristic of microblogging, the Twitter user tends to be engrossed in the flow of information from different users, roughly like someone reading articles in a newspaper, whereas the Weibo user tends to be immersed in the complicated world of the medium itself, an experience closer to the virtual reality of a role-playing game. In the second case, the rules and aesthetic qualities of the medium become much more important, with a consequent bias towards achievement, praise, and identity formation, and against argument, rhetoric, and discursive textual features. As Arora (2012, p. 607) suggests, there is a convergence between aestheticized Internet spaces (personalized spaces, where the individual is encouraged actively to engage with the design features provided) and private spaces: if users come to see Weibo as their “home”, they may be less likely to engage in the controversial “public” discourse which takes place on it. Finally, lack of user control over the interface. I have already discussed how Twitter users, in Santo’s terms, “hacked” the simple text-based interface of the site, using a variety of symbols and bespoke terms, to organize their social sphere and facilitate the transfer of information: examples of this include hashtags, retweets, and abbreviated web links to images. In some cases, these unofficial features have been incorporated officially into the Twitter interface, sometimes to the disapproval of users who had a sense of ownership over the “hacks” their community developed (see Barone, 2009, for example). Generally speaking, however, the Twitter medium has remained relatively stable: changes to the interface have generally 13 resulted as a consequence of a particular “hack” becoming so popular that it is ultimately officially adopted, in what might be called a bottom-up, negotiative process. The interface features of Sina Weibo, on the other hand, have been implemented in a topdown fashion. The “hacks” of Weibo users — the most important of which relate to the manipulation of language to avoid censorship — are ignored or opposed by Weibo management. Beyond this, the interface lacks “hackability”. Its relatively complex array of features means that there is much less need for users to invent their own ways of communicating. Images can be displayed inline automatically; there is a feature for commenting directly on posts, rather than using the “@ reply” function that Twitter has (where replies are made in a separate post with the original poster’s username at the start); the plethora of recommendations, interest groups, and social networks reduces the utility of hashtags. Furthermore, these Weibo features are modular, which is to say that they can be removed selectively if demanded by the state or management. For example, in March 2012, when confronted with rumours about a coup involving Bo Xilai, the Weibo management was able to remove the commenting feature (illustrated in Figure 4), thus stifling replies to posts and facilitating a much more rapid process of censorship (Johnson, 2012). The Weibo interface, therefore, is deconstructable at the will of the state; it can be manipulated to fulfill the particular aims of the hegemon. Twitter, on the other hand, relies far more on media (such as weblinks, offsite images, and so on) which are hosted on sites not controlled by Twitter or by a particular state, and, despite the fact that its interface has increased in complexity over time, the fundamental medium of Twitter communication still remains the 140-character Unicode text string. This cannot be said of Sina Weibo. Figure 4: Forwarding and commenting on Weibo: user comments are integrated with posts, rather than being made in separate posts as on Twitter. 14 These three factors, I suggest, work to alter the Chinese microblog medium at a fundamental level. They are state-initiated rather than cultural or pragmatic, and many of them are, or are intended to be, transparent to the user. Their collective aim is to weaken the capacity for individual citizens to discuss contentious topics in depth, and, in parallel, to enhance a consumption-focused entertainment culture developed by the state and the market elite. In doing so, they lend weight to Arns’ arguments about the “panoptical and post-optical” aspects of the interface and Hoofd’s about the “speed-elite” and activism. Equally, though, this analysis should not be taken as signifying that contentious political discussion is impossible on Weibo. In fact, it clearly takes place all the time: with the number of users, the breadth of Internet access, and the finite ability of the state to censor, it would be impossible for it not to. The point of this section, however, is to demonstrate that the state has developed strategies for controlling Internet users which do not merely target flows of information, but which also intend to manipulate styles of communication and the choices and mindsets of users — and, importantly, which also aim to limit the palette of strategies to which activists and contentious communicators themselves have access. Conclusion Writing before the advent of microblogs, Rancière — together with Slavoj Žižek, who offered comments on the English edition of The Politics of Aesthetics — considered the possibility that aesthetically new forms of communication might create new spaces for citizens excluded from elite groups to assert wrongs, make demands, and participate in the public sphere — not necessarily as speakers in a formal, rational debate, but more as “legitimate partners” whose voices were heard in an ongoing process of political discourse (Žižek, 2004, pp. 69-71). The case of Sina Weibo stimulates reflection on this principle in interesting ways. The modification of the microblog medium by Sina Corporation — with the support of the Chinese state —demonstrates the links between political communication and interface aesthetics. But in the Chinese case, the principle is working in reverse: with sufficient state control over the medium, it seems to be possible to manipulate the experience of microblog users to turn them away from political communication and towards consumption and entertainment. Furthermore, in the Chinese context, the techniques associated in the West with the “liberal paternalist” method of choice architecture promoted by Thaler and Sunstein are being used to stifle free access to information and discussion of contentious topics. That said, the principles of interface aesthetics and human-computer interaction demonstrate the potential of microblogs, or indeed any similar media which facilitate the rapid personalized flow of information to the isolated individual, in the sense of Baudrillard’s “private telematics”. The question of whether substantive debate is genuinely possible on microblogs is still difficult to answer. The metaphor of immersion and flow, together with Hoofd’s and Jodi Dean’s suggestions that the rapid exchange of data stifles detailed debate, must be borne in mind, but at the same time, the adaptation of microblogs by Chinese users demonstrates the discursive potential of microblogs as well as their capacity to entertain and advertise. The interfaces described in this article are in constant flux, however, and the question of how microblog users can mediate and negotiate user interfaces is unresolved. In a methodological sense, then, I would argue that a knowledge of the discipline of interface aesthetics will aid both academics and Internet users to understand how interfaces are being used to shape the transmission of information, and how these interfaces might be changed. 15 References Anonymous, Chinese vs. Western Web Design. 2010. http://www.backboneitgroup.com/china-search-differences.htm. Anonymous, Why Is Chinese Web Design So Bad? 2011. http://blog.teamtreehouse.com/why-is-chinese-web-design-so-bad. Anonymous, Zhejiang Tiantai xian jiang weibo xiezuo lieru ganbu xuanba kaoti. 2012. http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2012-07-24/035924830262.shtml. Andersen, Christian Ulrik, and Søren Bro Pold, eds. 2010. Interface criticism: aesthetics beyond buttons. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. Arns, Inke. 2010. Transparent World: Minoritarian Tactics in the Age of Transparency. In Interface criticism: aesthetics beyond buttons, edited by C. U. Andersen and S. B. Pold. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. Arora, Payal. 2012. Typology of Web 2.0 spheres: Understanding the cultural dimensions of social media spaces. Current Sociology 60 (5):599-618. Bamman, David, Brendan O'Connor, and Noah A. Smith. 2012. Censorship and deletion practices in Chinese social media. First Monday (3), http://www.uic.edu/htbin/cgiwrap/bin/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/3943/3169. Bandurski, David. 2011. China tackles the messy world of microblogs. http://cmp.hku.hk/2011/08/11/14706/. Barone, Lisa. 2009. Why Twitter’s New Retweet Feature Sucks. http://outspokenmedia.com/social-media/twitters-new-retweet-feature-sucks/. Baskerville, Rachel F. 2003. Hofstede never studied culture. Accounting, Organizations and Society 28:1-14. Baudrillard, Jean. 1988. The Ecstasy of Communication. New York, NY: Semiotext(e). Benney, Jonathan. 2011. Twitter and Legal Activism in China. Communication, Politics & Culture 44 (1):5-20. Berg, Daria, and Giorgio Strafella. 2012. A Twitter Bodhisattva: Ai Weiwei’s Media Politics. In Conference on Modes of Activism and Engagement in the Chinese Public Sphere. Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. Bertelsen, Olav W., and Søren Pold. 2004. Criticism as an Approach to Interface Aesthetics. Paper read at Proceedings of the third Nordic conference on Human-computer interaction, at Tampere, Finland. Bourges-Waldegg, Paula, and Stephen A.R. Scrivener. 1998. Meaning, the central issue in cross-cultural HCI design. Interacting with Computers 9:287-309. Bratton, Benjamin H., and Natalie Jeremijenko. 2009. Suspicious Images, Latent Interfaces. New York, NY: The Architectural League of New York. Brown, Christopher, Joey Frazee, David Beaver, Xiong Liu, Fred Hoyt, and Jeff Hancock. 2011. Evolution of Sentiment in the Libyan Revolution. https://webspace.utexas.edu/dib97/libya-report-10-30-11.pdf. Bruns, Axel, and Jean E. Burgess. 2011. The use of Twitter hashtags in the formation of ad hoc publics. Paper read at 6th European Consortium for Political Research General Conference, at Reykjavik, Iceland. Chan, Alex. 2007. Guiding public opinion through social agenda-setting: China's media policy since the 1990s. Journal of Contemporary China 16 (53):547-559. Chander, Anupam. 2012. Jasmine Revolutions. Cornell Law Review 97 (6):1505-1531. Chang, Hsia-Ching. 2010. A New Perspective on Twitter Hashtag Use: Diffusion of Innovation Theory. Proceedings of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 47 (1):1-4. 16 Chen, Junting, and J. She. 2012. An Analysis of Verifications in Microblogging Social Networks -- Sina Weibo. Paper read at 2012 32nd International Conference on Distributed Computing Systems Workshops (ICDCSW), at Macau. Chen, Shaoyong, Huanming Zhang, Min Lin, and Shuanghuan Lü. 2011. Comparision of Microblogging Service Between Sina Weibo and Twitter. Paper read at 2011 International Conference on Computer Science and Network Technology, at Harbin, China. Chin, Josh, and Loretta Chao. 2011. Beijing Communist Party Chief Issues Veiled Warning to Chinese Web Portal. Wall Street Journal, http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111904279004576526293276595886.ht ml. Cramer, Florian. 2010. What is Interface Aesthetics, or What Could It Be (Not)? In Interface criticism: aesthetics beyond buttons, edited by C. U. Andersen and S. B. Pold. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. Dean, Jodi. 2010. Blog Theory: Feedback and Capture in the Circuits of Drive. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. Ess, Charles. 2007. From Computer-Mediated Colonization to Culturally Aware ICT Usage and Design. In Advances in Universal Web Design and Evaluation: Research, Trends and Opportunities, edited by S. Kurniawan and P. Zaphiris. Hershey, PA: IGI Global. Esselink, Bert. 2000. A Practical Guide to Localization. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Faiola, Anthony, and Sorin A. Matei. 2006. Cultural Cognitive Style and Web Design: Beyond a Behavioral Inquiry into Computer-Mediated Communication. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 11:375-394. Fu, King-Wa, and Michael Chau. 2013. Reality Check for the Chinese Microblog Space: A Random Sampling Approach. PLOS ONE, http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0058356. Gao, Qi, Fabian Abel, Geert-Jan Houben, and Yong Yu. 2012. A Comparative Study of Users' Microblogging Behavior on Sina Weibo and Twitter. Paper read at UMAP'12 Proceedings of the 20th international conference on User Modeling, Adaptation, and Personalization. Glaser, Mark. 2007. Twitter Founders Thrive on Micro-Blogging Constraints. Mediashift, http://www.pbs.org/mediashift/2007/05/twitter-founders-thrive-on-micro-bloggingconstraints137.html. Goldkorn, Jeremy. 2011. YouTube = Youku? Websites and Their Chinese Equivalents. Fast Company, http://www.fastcompany.com/1715042/youtube-youku-websites-and-theirchinese-equivalents. Hall, Edward T., and Mildred Reed Hall. 1990. Understanding Cultural Differences. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press. Hassid, Jonathan. 2012. Safety Valve or Pressure Cooker? Blogs in Chinese Political Life. Journal of Communication 62 (2):212-230. ———. 2012a. The Politics of China’'s Emerging Micro-Blogs: Something New or More of the Same? , http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2106459. Herold, David Kurt. 2011. Introduction: noise, spectacle, politics: carnival in Chinese cyberspace. In Online Society in China, edited by D. K. Herold and P. Marolt. Oxford: Routledge. Hofstede, Geert. 1980. Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work-Related Values. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage. Honeycutt, Courtney, and Susan C. Herring. 2009. Beyond Microblogging: Conversation and Collaboration via Twitter. Paper read at Proceedings of the 42nd Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, at Waikoloa, Big Island, Hawaii. 17 Hong, Lichan, Gregorio Convertion, and Ed H. Chi. 2011. Language Matters in Twitter: A Large Scale Study. Paper read at Fifth International AAAI Conference on Weblogs and Social Media (ICWSM'11), at Barcelona; Spain. Hoofd, Ingrid M. 2012. Ambiguities of Activism: Alter-Globalism and the Imperatives of Speed. New York, NY: Routledge. Hsu, Jeffrey. 2003. Chinese Cultures and E-Commerce. In E-Commerce and Cultural Values, edited by T. Thanasankit. Hershey, PA: Idea Group Publishing. Hu, Xin. 2002. The Surfer-in-Chief and the Would-be Kings of Content: A Short Study of Sina.com and Netease.com. In Media in China: Consumption, Content and Crisis, edited by S. H. Donald, M. Keane and H. Yin. London: RoutledgeCurzon. Hughes, Amanda, and Leysia Palen. 2010. Twitter Adoption and Use in Mass Convergence and Emergency Events. International Journal of Emergency Management 6 (3-4):248260. Java, Akshay, Xiaodan Song, Tim Finin, and Bell Tseng. 2007. Why We Twitter: Understanding Microblogging Usage and Communities. Paper read at Joint 9th WEBKDD and 1st SNA-KDD Workshop ’07, at San Jose, California, USA. Jeffreys, Elaine, and Louise Edwards. 2010. Celebrity/China. In Celebrity in China, edited by L. Edwards and E. Jeffreys. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. Johnson, Ian. 2012. Coup Rumors Spur China to Hem in Social Networking Sites. New York Times, 31 March 2012. Kennedy, Scott. 1997. The Stone Group: State Client or Market Pathbreaker? The China Quarterly 152:746-777. Kraus, Richard Curt. 2004. The Party and the Arty in China. Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield. Lagerkvist, Johan. 2012. Principal-Agent Dilemma in China’s Social Media Sector? The Party-State and Industry Real-Name Registration Waltz. International Journal of Communication 6:2628-2646. Lauren, Brenda K. 1984. Interface as Mimesis. In User Centered Systems Design: New Perspectives on Human-Computer Interaction, edited by D. A. Norman and S. W. Draper. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Liu, Chang. 2012. Weibo wenzheng, zhili zhuanxing yu "lingzui shehui gongcheng". Nanjing shehui kexue (4):110-116. Liu, Yinbin, and Yixia Zhuo. 2011. Social Media in China: Rising Weibo in Government. Paper read at 5th IEEE International Conference on Digital Ecosystems and Technologies, at Daejeon, Korea. Liu, Zhengjie, Jun Zhang, Haixin Zhang, and Junliang Chen. 2011. Usability in China. In Global Usability, edited by I. Douglas and Z. Liu. London: Springer-Verlag. Longford, Graham. 2005. Pedagogies of Digital Citizenship and the Politics of Code. Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology 9. Lovink, Geert. 2003. My First Recession: Critical Internet Culture in Transition. Rotterdam: V2_Publishing in collaboration with NAiPublishers. Lukoff, Kai. 2011. Sina Weibo is for Fun, Twitter is more for News. http://techrice.com/2011/07/18/sina-weibo-is-for-fun-twitter-is-more-for-news-study/. Lunenfeld, Peter. 2011. The Secret War Between Downloading And Uploading: Tales of the Computer as Culture Machine. Boston, MA: MIT Press. McSweeney, Brendan. 2002. Hofstede’s Model of National Cultural Differences and their Consequences: A Triumph of Faith - a Failure of Analysis. Human Relations 55 (1):89-118. Meng, Bingchun. 2010. Moving beyond democratization: A thought piece on Chinese Internet research agenda. International Journal of Communication 4:501-508. 18 ———. 2011. From steamed bun to grass mud horse: E gao as alternative political discourse on the Chinese Internet. Global Media and Communication 7 (1):33-51. Millward, Steven. 2009. Sina's Twitter-esque microblogging site: A closer look. http://asia.cnet.com/blogs/sinas-twitter-esque-microblogging-site-a-closer-look62115894.htm. Mischaud, Edward. 2007. Twitter: Expressions of the Whole Self: An investigation into user appropriation of a web-based communications platform, Department of Media and Communications, London School of Economics and Political Science, London. Morozov, Evgeny. 2011. The Net Delusion: The Dark Side of Internet Freedom. New York, NY: PublicAffairs Books. Nielsen, Henrik Kaare. 2010. The Net Interface and the Public Sphere. In Interface criticism: aesthetics beyond buttons, edited by C. U. Andersen and S. B. Pold. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press. O'Carroll, Lisa. 2012. Twitter active users pass 200 million. The Guardian. Ong, Josh. 2012. China’s Sina Weibo passes 400m users, acknowledges pressure from rival Tencent’s WeChat. The Next Web, http://thenextweb.com/asia/2012/11/16/sina-books152-million-in-q3-revenue-as-it-faces-tough-competition-from-tencents-wechat/. Pold, Søren. 1999. An Aesthetic Criticism of the Media: The Configuration of Art, Media and Politics in Walter Benjamin's Materialistic Aesthetics. Parallax 5 (3):22-35. Rancière, Jacques. 2004. The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. London: Continuum. Rancière, Jacques, Solange Guenoun, James H. Kavanagh, and Roxanne Lapidus. 2000. Jacques Rancière: Literature, Politics, Aesthetics: Approaches to Democratic Disagreement. SubStance 29 (2):3-24. Rockhill, Gabriel. 2004. Jacques Rancière's Politics of Perception. In The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. London: Continuum. Russell, Jon. 2011. Importance of microblogs in China shown as Weibos pass 550 million users. The Next Web, http://thenextweb.com/asia/2011/11/11/importance-ofmicroblogs-in-china-shown-as-weibos-pass-550-million-users/. Santo, Rafi. 2012. Hacker Literacies: Synthesizing Critical and Participatory Media Literacy Frameworks. International Journal of Learning and Media 3 (3):1-5. Shahid, Aliyah. 2010. Chinese woman, Cheng Jianping, sentenced to a year in labor camp over Twitter post. Daily News, 18 November 2010. Shank, Megan, and Jeffrey Wasserstrom. 2012. Anxious Times in a Rising China: Lurching Toward a New Social Compact. Dissent 59 (1):5-11. Sullivan, Jonathan. 2012. A tale of two microblogs in China. Media, Culture & Society 34 (6):773-783. Sunstein, Cass. 2001. Republic.com. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Tan, Chui Chui. 2011. Chinese Web Design Patterns: How and why they’re different. Thaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein. 2008. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. Wagner, Claudia, and Enrico Motta. 2009. Data Republishing on the Social Semantic Web. Paper read at Proceedings of the First Workshop on Trust and Privacy on the Social and Semantic Web (SPOT2009), at Heraklion, Greece. Wallis, Cara. 2012. Technomobility in China: Young Migrant Women and Mobile Phones. New York, NY: New York University Press. Walsham, Geoff. 2002. Cross-Cultural Software Production and Use: A Structurational Analysis. MIS Quarterly 26 (4):359-380. Wang, Jian. 2003. Human-Computer Interaction Research and Practice in China. Interactions (March/April 2003):88-96. 19 Wauters, Robin. 2009. China Blocks Access To Twitter, Facebook After Riots. http://techcrunch.com/2009/07/07/china-blocks-access-to-twitter-facebook-after-riots/. Wayant, N., A. Crooks, A. Stefanidis, A. Croitoru, J. Radzikowski, J. Stahl, and J. Shine. 2012. Spatiotemporal Clustering of Twitter Feeds for Activity Summarization. Paper read at Seventh International Conference on Geographic Information Science, at Columbus, OH. Weit, Skyler. 2012. Review: A Tale of Two Microblogs in China. TechRice, http://techrice.com/2012/04/04/review-a-tale-of-two-microblogs-in-china/. Williamson, Dermot. 2005. Forward from a Critique of Hofstede’s Model of National Culture. Human Relations 55 (11):1373-1395. Wright, Scott, and John Street. 2007. Democracy, deliberation and design: the case of online discussion forums. New Media and Society 9 (5):849-869. Würtz, Elizabeth. 2005. A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Websites from High-Context Cultures and Low-Context Cultures. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication (1), http://jcmc.indiana.edu/vol11/issue1/wuertz.html. Xiao, Qiang. 2011. The Battle for the Chinese Internet. Journal of Democracy 22 (2). Yang, Guobin. 2009. The Power of the Internet in China: Citizen Activism Online. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. Yang, Jian. 2011. Weibo shidai women zenme piyao? Renmin Ribao (10 August 2011), http://news.sina.com.cn/pl/2011-08-10/073822965891.shtml. Yardi, Sarita, and danah boyd. 2010. Dynamic debates: An analysis of group polarization over time on Twitter. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 30 (5):316-327. Yu, Jincui. 2012. Weibo skills essential for officials to interact with public. Global Times, http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/723345.shtml. Yu, Louis, Sitaram Asur, and Bernardo A. Huberman. 2011. What Trends in Chinese Social Media. Paper read at The 5th SNA-KDD Workshop ’11, at San Diego, CA. Zhang, Zhian, and Jia Jia. 2011. Zhongguo zhengwu weibo yanjiu baogao. Xinwen jizhe (6):34-39. Zhou, Yongming. 2006. Historicizing Online Politics: Telegraphy, the Internet, and Political Participation in China. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Zhu, Zhichang. 1998. Confucianism in Action: Recent Development in Oriental Systems Methodology. Systems Research and Behavioral Science 15:111-130. Žižek, Slavoj. 2004. The Lesson of Rancière. In The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible. London: Continuum. 20