Health Complaints and Outcome Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease

advertisement

Health Complaints and Outcome Assessment in Coronary Heart Disease

JOHAN DENOLLET, PH.D.

Research on coronary heart disease (CHD) lacks sensitive outcome measures. Health complaints, although

subjective in nature, may provide information on the degree of recovery from CHD. The purpose of Study 1

was to identify common health complaints in a group of 535 men (mean age, 57.5 years) with CHD. In the

weeks after a coronary event, they frequently reported somatic (e.g., chest pain, dyspnea, fatigue, sleep

problems) and cognitive (e.g., concern about health and functional status) health complaints. Statistical

analyses produced the Health CompJaints Scale (HCS), which comprises 12 somatic and 12 cognitive

complaints. Confirmatory factor analysis provided evidence for the model undergirding the HCS, and the

somatic and cognitive scales of the HCS were found to have high internal consistency (a > .89), adequate

test-retest reliability (r > .69), and good construct validity. Study 2 provided evidence for the idea that the

HCS can be distinguished from standard scales of psychopathology. Statistical analyses in 266 men with CHD

indicated that, compared to symptoms of psychopathology, the HCS scales displayed discrete factor loadings

as well as higher scores at baseline and a normal clustering of scores. Important to note, HCS scores decreased

in 60 subjects participating in cardiac rehabilitation (p < .0001) but not in 60 control subjects. Although

research should not disregard psychological biases on symptom reporting, it is argued that health complaints

need to be accurately assessed in CHD patients.

Key words: coronary heart disease, health complaints, outcome assessment, quality of life, cardiac rehabilitation.

INTRODUCTION

Outcome assessment in medical settings is a matter that will receive considerable attention in the

coming years (1). It is important that health care

professionals have finely tuned, sensitive measures

in order to keep track of the impact of chronic

disease on functional status and well being and to

monitor the effects of their care on these outcomes

(2). Research on recovery from coronary heart disease (CHD), however, lacks standardized instruments for measuring psychological constructs that

match the theoretically prescribed effect of treatment in this population (3). That is, standard distress

scales predominantly measure the stable disposition

to experience negative emotions (i.e., negative affectivity) in patients with CHD (4) and thus are less

sensitive to change. Scales that were specifically

designed for patients with CHD may be more appropriate to assess psychological effects of treatment (5).

Of note, findings from the Medical Outcomes

Study indicate that CHD is a medical condition that

has a significant impact on the patient's perceived

health status (2). Decrements in perceived health, in

From the University Hospital of Antwerp, Antwerp, Belgium.

Address reprint requests to: Johan Denollet, Ph.D., UZA —

Cardiale Revalidatie, Wilrijkstraat, 10, B-2650 Edegem, Belgium.

Received for publication March 26, 1993; revision received

October 25, 1993.

Psychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)

0033-3174/94/5605-0463S03.00/0

Copyright © 1994 by (he American Psychosomatic Society

turn, are intimately linked to psychosocial morbidity associated with CHD, including the likelihood of

seeking medical care (6) and failure to return to

work (7). In fact, one of the primary goals of health

care for these patients is to enhance daily functioning (8). It follows that health complaints, although

not always paralleling the seriousness of CHD, may

provide information on the degree of psychosociaJ

recovery from CHD. Therefore, this paper addresses

the assessment of health complaints in the context

of CHD. Study 1 focused on the prevalence of health

complaints and the construction of a new scale.

Study 2 focused on the rationale for using health

complaints as an outcome measure in CHD.

STUDY 1: ASSESSMENT OF HEALTH

COMPLAINTS

First, the assessment of health complaints should

be relevant from a theoretical point of view. Accordingly, a limited number of somatic and cognitive

symptom clusters, rather than a heterogeneous conglomerate of symptoms, were studied. Somatic

health complaints focused on "cardiopulmonary

problems," "fatigue," and "sleep problems" symptom

clusters. These health complaints have been associated with myocardial infarction and cardiac death

(9-13) and with coronary risk factors, such as hypercholesterolemia (14). Cognitive health complaints focused on the "health worry" (i.e., anxious

concern about health) and "illness disruption" (i.e.,

463

J. DENOLLET

concern about the extent to which illness interferes

with one's life) symptom clusters that were identified in the psychometric analysis of the illness behavior concept (15). Self-ratings of poor health (16)

and functional status (17) have been associated with

mortality.

Second, the assessment of health complaints

should also be relevant from the patient's point of

view. Accordingly, research needs to identify health

complaints that occur frequently in patients with

CHD. Traditional psychometric measures may be

burdensome for nonclinical (with respect to mental

health) populations to complete on a frequent basis

(18). The more burdensome the scale, the greater

likelihood of poor response rate or quality of data

(19). Health complaints with a high frequency of

endorsement, however, are likely to comprise a

measure that may be perceived as being immediately relevant to patients with CHD. The purposes

of Study 1 were to: a) identify somatic and cognitive

health complaints that occur frequently in patients

recovering from a coronary event; and b) devise, on

this basis, a psychometrically sound scale of selfreported health complaints in CHD. Specifically, the

focus was on the primary factors (i.e., the a priori

defined symptom clusters) and their relationship to

the second-order construct of self-rated health in

the context of CHD.

METHOD

Subjects

Subjects were 535 men with CHD drawn from four hospitals

in the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium: the University (N = 341),

Middelheim (N = 105) and Saint Jozef (N = 16) hospitals in

Antwerp, and the Maria's Voorzienigheid Hospital (N = 73) in

Kortrijk. Subjects of the University Hospital were referred by

their attending physician to an outpatient rehabilitation program;

subjects from the other hospitals either participated in homebased cardiac rehabilitation or received standard medical care.

The mean age was 57.5 years (SD = 8.6). All subjects agreed to

participate in the study and filled out questionnaires at 3 to 6

weeks after the incidence of myocardial infarction {MI, N = 126),

coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG, N = 324), or percutaneous

transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA, N = 85).

Assessment of Health Complaints

An initial item pool of 20 somatic and 20 cognitive health

complaints was based on: a) items that were derived from the

Illness Behavior Questionnaire (20), the Heart Patients Psychological Questionnaire (21), and the SCL-90 (22); and b) items that

were specifically written for the purpose of this study. The Illness

Behavior Questionnaire predominantly taps cognitive modes of

responding to one's state of health (15). The Heart Patients Psy-

464

chological Questionnaire comprises items that address the discrepancy between the time before and after onset of an acute

coronary event. The SCL-90 contains a number of cardiopulmonary complaints and one item that reflects concern with global

health.

Subjects were asked to rate how much they had been bothered

lately by each health complaint on a 5-point scale of distress

ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (extremely). In order to provide a

representative picture of relatively enduring changes in subjective health, "lately" was used as a temporal reference. The time

frame depends on the researcher's interest. If one wishes to assess

rapid changes in a patient's condition that are associated with

particular events (e.g., CABG) a more specific time frame (e.g.,

past week) may be used. Statistical analyses in a subset of 205

subjects were used to reduce the initial item pool; health complaints with a high endorsement frequency, factor loading, and

corrected item-scale correlation were retained. Health complaints

with too much redundancy were deleted. An intermediate 30item scale was administered to a second subsample, and further

analyses produced 12 somatic and 12 cognitive items, each describing a common health complaint.

Construct Validity

The following scales were used to examine the construct

validity of the self-reported health complaints. The disability

scale of the Heart Patients Psychological Questionnaire (21) was

predicted to correlate positively, and the well being scale to

correlate negatively with health complaints. Health complaints

were also validated against three broad and stable personality

traits: negative affectivity, self-deception, and social inhibition.

Negative affectivity is the tendency to experience somatic and

emotional distress (23) and is assessed well by the trait scale of

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. The Dutch adaptation of this scale

(24) was predicted to correlate positively with self-reported health

complaints. Self-deception and social inhibition are two traits

that are distinctly different from negative affectivity. Self-deception is the tendency to remain unaware of unpleasant emotional

realities and is assessed well by the Marlowe-Crowne scale (25).

Social inhibition is the tendency to inhibit one's feelings and

behaviors and is assessed well by the social inhibition scale of

the Heart Patients Psychological Questionnaire (21). Importantly,

these self-deception and social inhibition measures were predicted to be largely unrelated to self-reported health complaints.

Procedure and Statistical Analysis

All subjects filled out a questionnaire comprising the somatic

and cognitive symptom clusters that were devised on theoretical

grounds. In order to isolate items with a high frequency of

endorsement, the frequency distribution of each health complaint

was calculated. The self-reported health complaints were analyzed on two levels in the hierarchy of constructs: the first-order

level where each item is more or less an alternate form of each

other item and the second-order level that is defined by the

intercorrelations among symptom clusters (26). Confirmatory factor analysis was used to examine the accuracy of both the firstorder (i.e., specific symptom clusters) and second-order (i.e., general construct of self-rated health as defined by intercorrelations

among symptom clusters) a priori model. Important to note, one

can develop a test of the model's fit with this statistical method.

LISREL VI was used for this purpose (27). Exploratory factor

Psychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)

HEALTH COMPLAINTS IN CHD

analysis was used to examine the intercorrelations among somatic

and cognitive health complaints. Scree plot and eigenvalue criteria were used to decide on the optimum number of factors to

retain. Cronbach's a was used to obtain internal-consistency

estimates of reliability of the scales that emerged from these

analyses. Pearson's correlations and exploratory factor analysis

were used to examine the construct validity of the self-reported

health complaints.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Assessment of Health Complaints

The majority of somatic health complaints were

marked positively (i.e., score > 0) in at least 50% of

the cases (Table 1). A confirmatory 3-factor solution

indicated that of the 12 somatic health complaints,

five were related to the "cardiopulmonary," four to

the "fatigue," and three to the "sleep problems" a

priori symptom clusters. The goodness of fit index

for this first-order model of somatic complaints was

.92. Cronbach's a indicated an adequate level of

internal consistency for each of these symptom clusters (a = .80, .91, and .89, respectively). Exploratory

factor analysis of the 24 somatic and cognitive health

complaints yielded two factors that accounted for

56% of the total variance. Scree plot indicated that

eigenvalues tended to level after the second factor.

All of the somatic health complaints had their highest loading on Factor II. Accordingly, corrected itemtotal correlations indicated that cardiopulmonary

complaints, fatigue, and sleep problems tended to go

together in this population of coronary patients (a =

.89).

Eleven cognitive health complaints were marked

positively (i.e., score > 0) in at least 50% of the cases

(Table 2). A confirmatory two-factor solution indicated that six cognitive complaints were related to

the "health worry" and six to the "illness disruption"

a priori cluster. The goodness of fit index for this

first-order model of cognitive complaints was .90.

Cronbach's a indicated an adequate level of internal

consistency for both the "health worry" and "illness

disruption" symptom clusters (a = .92 and .91, respectively). Further, exploratory factor analysis of

the 24 health complaints showed that all of the

cognitive health complaints had their highest loading on Factor I. Cronbach's a indicated a high level

of internal consistency (a — .95), and 11 cognitive

complaints had corrected item-total correlations

greater than .70. In general, these findings suggest

the psychometric soundness of the a priori symptom

clusters that were conceptualized for the assessment

of health complaints at the first-order level.

Consistent with the higher order model of perceived health, the somatic and cognitive symptom

clusters were found to be highly intercorrelated, and

confirmatory factor analysis indicated the existence

of one, single second-order construct (Table 3). The

goodness of fit index for this second-order model

was .92. Corrected item-total correlations and Cronbach's a (.84) provided further evidence for the

existence of a general, broad, second-order factor.

TABLE 1. Frequency of Endorsement, Factor Loading, and Internal Consistency of Somatic Health Complaints [N = 535)

Item

N

A Priori Symptom Clusters

Frequency of

Endorsement1

Confirmatory

Factor Analysis*

L1

A10.

A9.

A2.

A6.

A7.

Pain in heart or chest

Shortness of breath

Tightness of the chest

Inability to take a deep breath

Stabbing pain in heart or chest

52%

51%

50%

43%

36%

A4.

A11.

A3.

A8.

Fatigue

Feeling weak

Feeling that you are not rested

Feeling exhausted without any reason

69%

66%

57%

49%

A1.

A5.

A12.

Sleep that is restless or disturbed

Trouble falling asleep

Feeling you can't sleep

64%

60%

49%

L2

L3

.67

.72

.70

.67

..56

.87

.81

.82

.88

.76

.88

.93

Exploratory

Factor

Analysis*

Internal

Consistency*

I

II

.21

.22

.22

.16

.21

.60

.61

.58

.59

.50

.55

.56

.55

.51

.47

.45

.46

.38

.38

.64

.61

.68

.69

.69

.67

.71

.73

.12

.07

.08

.63

.67

.66

.55

.57

.57

' Mean = 54%.

•Analysis of the 12 somatic health complaints; L1-L3, Lisrel estimates (maximum likelihood).

' Analysis of the 24 somatic and cognitive health complaints; l-ll, extracted factors; items assigned to a factor are in boldface; eigenvalue

1 = 2.33.

* Corrected item-total correlations for the Somatic Complaints scale; Cronbach's a = .89.

Psychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)

465

J. DENOLLET

TABLE 2. Frequency of Endorsement, Factor Loading, and Internal Consistency of Cognitive Health Complaints [N = 535)

Confirmatory

Item

..

N

* D• •c

.

r-,

A Priori Symptom Clusters

Frequency of

,

' ,

c

Endorsement"

Exploratory

Factor

Factor

B11.

B3.

B8.

B6.

B12.

B1.

Worrying about health

Being afraid of illness

Something serious is wrong with body

The idea that you have a serious illness

All worries over if physically healthy

Bad health is the biggest problem in life

71%

59%

56%

52%

52%

51%

Analysis*

/Midiys.1;.

L2

L1

.83

.77

.88

.84

.76

.83

B4.

B9.

B5.

B7.

B2.

B10.

Able to take on much more work formerly

No longer worth as much as used to be

Feeling blocked in getting things done

Feeling you are not able to do much

Not being able to work fluently

Feeling despondent

78%

76%

75%

70%

66%

49%

.82

.82

.84

.78

.76

.74

Analysis'

""d'"bl:>

I

II

.79

.22

.76

.16

.84

.17

.82

.16

.75

.22

.80

.17

.73

.79

.70

.63

.61

.63

.29

.25

.39

.47

.45

.48

Internal

rJ

Consistency'

.78

.71

.81

.77

.74

.76

.74

.79

.77

.72

.69

.72

8

Mean = 63%.

'Analysis of the 12 cognitive health complaints; L1-L2, Lisrel estimates (maximum likelihood).

' Analysis of the 24 somatic and cognitive health complaints; l-ll, extracted factors; items assigned to a factor are in boldface; eigenvalue

= 11.03.

* Corrected item-total correlations for the Cognitive Complaints scale; Cronbach's a = .95.

TABLE 3. Intercorrelation Matrix and Secondary Factor Analysis of the Five A Priori Symptom Clusters (N = 535)

IntercomNation Matrix*

2.

3.

4.

5.

Confirmatory

Factor Analysis1

Internal

Consistency*

.60

.34

.43

.43

.54

.35

.55

.73

.37

60

.77

.41

.59

.73

.44

.78

.80

.96

.70

.83

A Priori Symptom Clusters

Somatic

1. Cardiopulmonary problems

2. Fatigue

3. Sleep problems

Cognitive

4. Health worry

5. Illness disruption

* All correlations, p < .001.

' Lisrel estimates (maximum likelihood).

' Corrected item-total correlations for the second-order factor of perceived illness; Cronbach's a = .84.

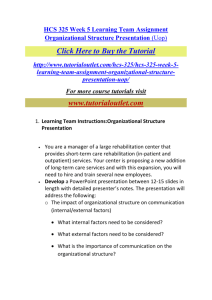

Because the five a priori symptom clusters were

found to measure a common dimension of perceived

health, this list of items was termed the Health

Complaints Scale (HCS) (Fig. 1). In further analyses,

HCS items were summed to obtain somatic and

cognitive health complaint scores that are situated

on the intermediate level of assessment that spans

the hierarchical levels of first-order and secondorder constructs (26).

Construct Validity of the Health Complaints

Scale

Correlations in the range of .54 to .66 indicated

that the somatic and cognitive health complaints

scores (range, 0-48) of the HCS shared 30 to 50%

variance with the disability and well being scales of

466

the Heart Patients Psychological Questionnaire

(Table 4). The HCS scales were also associated with

the tendency to experience distress as measured by

the negative affectivity scale (r = .53 and .60, respectively). Furthermore, the HCS was largely unre lated to measures of self-deception and social inh i b i t i o n (i.e., correlations in the range of .15 to .20).

I n k e e p i n g w i t h t h e s e findingS( exploratory factor

analysis yielded somatopsychic distress, self-deception, and social inhibition dimensions. In general,

these findings revealed a remarkably consistent pattern of convergent and discriminant validity of the

somatic and cognitive health complaints scales.

Clearly, male patients frequently experience

health complaints in the weeks after MI, CABG, or

PTCA. Patients with a spontaneous coronary event

(e.g., MI) reported less somatic complaints (M = 9.4,

Psychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)

HEALTH COMPLAINTS IN CHD

HCS

Name:

Sex:

Date:

Age:

Below are a number of problems and complaints that ill people often have. Please read e a c h item

carefully and then circle the a p p r o p r i a t e n u m b e r next to that problem. Indicate how much

each problem has b o t h e r e d you lately. Please use the following scale to record your answers.

0

SOI \ l M l

1

\ I II I I I - l;ll

2

M O D I |{ \ l l

Lately, how much were you bothered

by the following specific problems :

3 .H

III

\ lill

Lately, how much were you bothered

by the following general problems :

Sleep that is restless or

disturbed

0

1 2

3

Dl

The idea that your bad

health is the biggest

problem in your life

1 2

3

Tightness of the chest

0

1 2

3 4

02

Not being able to work

fluently, also with hobbies

1 2

2

Feeling that you are not

rested

0

1 2

3 4

Fatigue

0

1 2

3 4

m

The idea that you were able

to take on much more work

formerly

Trouble falling asleep

0

1 2

3 4

D5

Feeling blocked in getting

things done

-» 0

1 2

3 4

Inability to take a deep

breath

0

1 2

3

06

The idea that you have a

serious illness

0

1 2

3

Stabbing pain in heart or

chest

0

1 2

3 4

Feeling you are not able to

do much

1 2

3

A8

Feeling exhausted without

any reason

0

1 2

3 4

The 'idea that something

serious is wrong with

your body

1 2

3 4

A9

Shortness of breath

0

1 2

3 4

Feeling you are no longer

worth as much as you used

to be

12

3

'° Pain in heart or chest

0

1 2

3 4

Feeling despondent

0

1 2

3 4

Feeling weak

0

1 2

3 4

Worrying about your

health

0 1 2

3 4

Feeling you can't sleep

0

1 2

3 4

Thinking that all your

worries would be over if you

were physically healthy

0

3

A

Being afraid of illness

1)12

- ^ • 0 1 2 3 4

- ^ 0 1 2 3 4

0

1 2

4

4

Fig. 1. The Health Complaints Scale.

Psychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)

467

J. DENOLLET

TABLE 4.

Intercorrelation Matrix and Factor Loading of the HCS, HPPQ, STAI, and MC Scales [N = 535)

Intercorrelation Matrix *

HCS

1. Somatic complaints

2. Cognitive complaints

HPPQ

3. Disability

4. Well being

STAI

5. Negative affectivity

MC

6. Self-deception

HPPQ

7. Social inhibition

5.

Exploratory Factor Analysis'

Factor 1

Factor II

.15

.20

.82

.87

-.03

-.05

.02

.08

-.11

.23

.27

-.13

.75

-.83

.07

.21

.24

.00

-.29

.21

.72

-.37

.12

.00

-.10

.96

.01

.12

-.01

.98

3.46

1.05

0.89

2.

3.

4.

.67

.54

.59

-.55

-.66

.53

.60

-.15

-.15

-.54

.41

-.67

Eigenvalue

6.

7.

Factor III

HCS, Health Complaints Scale; HPPQ, Heart Patients Psychological Questionnaire; STAI, State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Dutch adaptation

of the trait form); MC, Marlowe-Crowne scale.

* All correlations: p < .01, except r = .00: not significant.

f

Loadings of scales that are assigned to a factor are in boldface.

SD = 8.6) than patients who underwent CABG or

PTCA (M = 11.8, SD = 8.8, F(l,533) = 7.12, p < .01).

On a cognitive level, however, neither group of

patients experienced significant differences in subjective health status (F(l,533) = 0.27, p = .60). Consistent with the findings of Study 1, by far the most

common problem reported by the subjects in the

Ischemic Heart Disease Life Stress Monitoring Program was concern about the impact of CHD on their

life (28). Not surprisingly, 80% of the interventions

in this trial focused on the implications of chest

pain, dyspnea, and fatigue. Factor analytic techniques in the present study clearly identified the

somatic and cognitive symptom clusters of cardiopulmonary problems, fatigue, sleep problems, health

worry, and illness disruption.

With reference to this issue, the variables measured by the HCS can be situated on different levels

in the hierarchy of constructs (26). At the lowest

level of this hierarchy (i.e., the level of the a priori

defined symptom clusters) each item is more or less

an alternate form of each other item. At the intermediate level of the hierarchy (i.e., the level of

somatic vs. cognitive health complaints) some of the

defining items for the factor are alternate-forms

types of items, but there are other items with substantial loadings that are not. At the highest level

(i.e., the level of intercorrelations among the various

symptom clusters) the five variables that define the

second-order construct of perceived health are correlated, but they are not alternate forms of one

another in their apparent logical content. Depending

on the researcher's interest, the symptom clusters of

468

the HCS can either be scored separately (assessment

of specific first-order constructs) or can be aggregated to obtain somatic and cognitive scores (assessment of more global constructs) or one single score

that reflects perceived health status (assessment of

one global second-order construct). In this study,

perceived health was measured at the intermediate

level of somatic and cognitive health complaints. On

the whole, the HCS appeared to be a reliable and

valid measure of health complaints in men with

CHD. However, given the fact that there already

exist a large number of widely used distress scales,

it is important to answer the question why a new

scale is needed. The purpose of Study 2 was to

address this central issue somewhat more in detail.

STUDY 2: HEALTH COMPLAINTS VS.

PSYCHOPATHOLOGY

There appears to be a tendency to use familiar

instruments, even if these instruments are less appropriate for the target population or the therapeutic

intervention under investigation. However, the

quality of outcome assessment depends heavily on

the theoretical relevance, the appropriateness, and

the responsiveness of the instruments used. Problems with standard distress scales in the context of

CHD may include measurement of wrong constructs

(3), lack of cover of relevant aspects (29), and a

limited range resulting in floor/ceiling effects (30).

For example, previous research suggests that

Psychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)

HEALTH COMPLAINTS IN CHD

standard measures of psychopathology may be less

appropriate to assess change in coronary patients

(target population) as a function of rehabilitation

(therapeutic intervention) (3). Measures that match

the theoretically prescribed effect of cardiac rehabilitation (i.e., enhancement of subjective health and

well being) are more appropriate to assess change in

this context. In other words, identifying appropriate

measures of key constructs is an important factor in

outcome assessment. Considerable difficulties may

also arise because many instruments are based on

what health care professionals regard as important

and take little account of the patient's view about

what is important (29). Items that are perceived as

being relevant to the patient's situation may comprise a measure that is appealing to complete. The

more burdensome the instrument, the greater likelihood of it not being completed. Finally, responsiveness (i.e., sensitivity to changes in what is being

measured) is a crucial requirement in quality of life

research (31).

The major flaw with the method of defining quality of life by the absence of psychopathology is that

this approach does not provide for supranormal levels of functioning and therefore can lead to underestimates of actual changes in quality of life. Therefore, evidence should be provided for the notion that

the HCS can be distinguished from standard scales

of psychopathology. Because the HCS and SCL-90

have the same item-format (a list of symptoms) and

response-format (a 5-point scale of distress), differences in construct validity, distribution of scores,

and responsiveness among these measures are likely

to reflect differences in content: health complaints

vs psychopathology. It is important to note that

research has shown that the SCL-90 is not sufficiently sensitive in the context of cardiac rehabilitation (3). The purpose of Study 2 was to examine:

a) the construct validity of health complaints vs.

symptoms of psychopathology; b) differences in

baseline scores of health complaints and psychopathology; and c) changes in health complaints as a

function of cardiac rehabilitation.

METHOD

Subjects and Measures

The study population consisted of two groups of men with

CHD. The first group was a subset of 266 subjects of Study 1 who

completed the Dutch adaptation of the SCL-90 (32). This adaptation of the SCL-90 comprises seven symptom dimensions that

closely resemble those of the original version (22): somatization,

obsessive-compulsive behavior, interpersonal sensitivity, depres-

Psychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)

sion, anxiety, hostility, and phobic anxiety. The second group

consisted of 120 men [mean age, 56.3 years) with CHD (MI N =

55, CABG N = 48, PTCA N = 17) who participated in an ongoing

trial of cardiac rehabilitation (3, 5). In brief, 60 of these 120

subjects received standard medical care at the Maria's Voorzienigheid Hospital of Kortrijk, and 60 subjects completed the rehabilitation program of the University Hospital of Antwerp between

July 1989 and December 1990. This 3-month program included

exercise training, health education, and individual psychosocial

counseling. The second group of subjects was used to examine

the responsiveness of the HCS because previous research indicated that rehabilitation subjects, but not control subjects, experienced significant improvements in perceived health status (3)

and subjective well being (3, 5). Because the cardiac rehabilitation

program is doing what it is claiming, the HCS scales should be

sensitive to changes in perceived health status that are associated

with this program.

Procedure and Statistical Analysis

Pearson's correlations and exploratory factor analysis were

used to examine the relationship between the HCS and SCL-90

scales (N = 266). Next, descriptive characteristics (mean, median,

quartiles, kurtosis, skewness) of both measures were examined.

In this analysis, a median split on the Trait Anxiety Scale (24)

classified subjects as being high (N = 131) or low (N = 135) in

their tendency to experience distress. The 120 subjects that

participated in the rehabilitation trial filled out the HCS scales

again at 3 months after the initial assessment (i.e., at the end of

rehabilitation in the experimental group). Repeated measures

MANOVA, with rehabilitation as between-subjects factor and

time as within-subjects factor, was used to analyze changes in

HCS scores. Finally, test-retest reliability was examined in the 60

control subjects receiving standard medical care alone.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Correlations that were mostly in the range of .50

to .70 indicated that the HCS and SCL-90 scales

shared 25 to 55% of variance (Table 5). Exploratory

factor analysis yielded two dimensions (eigenvalues

> 1.0) of subjective distress. Factor I was largely

defined by the SCL-90 scales, whereas Factor II was

defined by scales that were specifically designed for

cardiac patients. Of note, the SCL-90 scales predominantly reflected a general and broad dimension of

psychological distress in this population of coronary

patients. Despite the fact that both distress measures

have the same format, the HCS and SCL-90 appeared

to have a related, but not an identical, scope. This

finding corroborates the idea that the health complaints of the HCS can be distinguished jrom symptoms of psychopathoJogy in patients with CHD. The

strong factor loadings of the HCS and the Heart

Patients Psychological Questionnaire indicated that

these instruments were measuring a similar construct.

469

J. DENOLLET

TABLE 5.

Intercorrelation Matrix and Factor Loading of the HCS, HPPQ, and SCL-90 scales (N = 266)

Exploratory Factor

Analysis1

Intercorrelation Matrix*

HCS

1. Somatic Complaints

2. Cognitive Complaints

HPPQ

3. Disability

4. Well-Being

SCL-90

5. Somatization

6. Obsessive-Compulsive

7. Interpersonal Sensitivity

8. Depression

9. Anxiety

10. Hostility

11. Phobic Anxiety

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

-.63

-.69

.74

.68

.63

.66

.51

.58

.61

.71

.66

.74

.39

.39

.44

.60

.40

.50

.74

.71

-.67

.56

-.57

.50

-.52

.32

-.43

.47

-.63

.45

-.64

.30

-.35

.35

-.48

.11

-.29

.86

-.82

.74

.62

.74

.74

.70

.77

.74

.69

.69

.86

.48

.54

.60

.54

.55

.60

.62

.55

.71

.71

.36

.62

.71

.87

.79

.77

.74

.68

.60

.46

.20

.46

.49

.10

.35

6.95

1.09

2.

3.

4.

.73

.57

.58

10.

11.

Eigenvalue

Factor 1

Factor II

HCS, Health Complaints Scale; HPPQ, Heart Patients Psychological Questionnaire; SCL-90, Symptom Check List (Dutch adaptation).

* All correlations: p < .001.

' Loadings of scales that are assigned to a factor are in boldface.

TABLE 6.

Descriptive Characteristics of the HCS and SCL-90 Instruments [N = 266)*

Total Croup

High Distress (N = 131)

Low Distress (N = 135)

Descriptive Characteristics

Mean

Standard deviation

Median

Frequency distribution of scores

(quartiles)

0-24

25-49

50-74

75-100

HCS

SCL-90

HCS

SCL-90

HCS

25.1

20.8

19

12.8

11.9

10

35.8

21.7

33

19.5

12.9

16

14.7

13.4

10

6.4

57

5

57%

28%

12%

3%

85%

14%

1%

0%

35%

39%

21%

5%

70%

28%

2%

0%

80%

16%

4%

0%

100%

0%

0%

0%

SCL-90

* HCL denotes extrapolated total score (range 0-100) of the Health Complaints Scale; SCL-90 denotes extrapolated General Severity

Index (range 0-100) of the Symptom Check List.

Apart from construct validity (or theoretical relevance), a major point in the development of the HCS

is its appropriateness (or relevance from the patient's

point of view). Undoubtedly, the Global Severity

Index of the SCL-90 is a good marker of psychopathology. This implies that the distribution of SCL-90

scores reflects the actual self-report of psychiatric

symptoms in CHD populations. However, the present research did not focus on psychopathology but

on self-rated health. If the notion that coronary

patients may perceive HCS items as being more

relevant to their situation than SCL-90 items is correct, then HCS scores should be significantly higher

than SCL-90 scores. To test this hypothesis, differencesin the frequency distribution of the mean HCS

and SCL-90 scores at baseline were examined.

470

It is important to note that evidence suggests that

an instrument with a less skewed distribution may

sensitively reflect subclinical improvements in selfrated health as a function of cardiac rehabilitation

(3). Because the HCS was specifically designed to

have less extreme response categories than the SCL90, the HCS should be less skewed toward severe

pathology than the SCL-90. Because both instruments have a different range of scores, baseline

scores with a range of 0 to 100 were first extrapolated

in the following manner: HCS = total score/24 x 25;

SCL-90 = total score/90 X 25. Next, the distribution

of these scores was examined (Table 6).

The mean HCS score was twice as high than the

mean SCL-90 score (p < .0001). This difference in

HCS and SCL-90 baseline scores was found in both

Psychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)

HEALTH COMPLAINTS IN CHD

TABLE 7.

Mean HCS Entry and End Scores, and Analyses of Variance Results for Rehabilitation and Control Subjects (A' = 120)*

HCS Scale

Somatic complaints

Rehabilitation (N = 60)

Entry Score

End Score

Change

10.1 (7 3)

6.1 (7.5)

-4.0]

10.4 (8.8)

11.1 (8.9)

+0.7J

13.6(10.5)

8.9 (8.3)

-4.7]

14.4 (10.5)

16.0(11.2)

+ 1.6J

Rehabilitation x Time

Interaction Effect

F(1,118) = 19.32,

Control (N = 60)

Cognitive complaints

Rehabilitation (N = 60)

\

Control (N = 60)

p<.0001

F(1,118) = 24.16, p < . 0 0 0 1

* HCS denotes Health Complaints Scale; entry score, mean score within 6 weeks after the coronary event; end score, mean score 3

months after the initial assessment; standard deviations appear in parentheses.

high-distress and low-distress subjects (p < .0001).

Furthermore, the SCL-90 scores were largely restricted to the lower quartiles, whereas the HCL

scores could be found in the higher quartiles as well.

The HCS scores also displayed a normal clustering

around a central point (kurtosis = 0.09), whereas the

SCL-90 clearly displayed a peaked distribution of

low scores (kurtosis = 1.63). Both scales were skewed

to the right, but the HCS (skewness = 0.96) to a lesser

extent than the SCL-90 (skewness = 1.43). The fact

that standard distress scales are usually skewed toward more severe disability makes it difficult to

measure improvement after treatment (29). In general, these findings are consistent with the notion

that patients with CHD may perceive the items of

the HCS as being more reJevant to their situation

than the items of the SCL-90.

A final point in the development of the HCS concerns its sensitivity to change as a function of treatment. In a previous study, the differential sensitivity

to change of the SCL-90 and the Heart Patients

Psychological Questionnaire was examined in a

sample of 162 men with CHD who completed the

Antwerp cardiac rehabilitation program (3). The results of this study indicated that the SCL-90 was

significantly less sensitive to change than the Heart

Patients Psychological Questionnaire. Furthermore,

the anxiety, depression, and hostility subscales of

the SCL-90 were not sensitive enough to detect

actual changes in quality of life in patients who

report a low level of emotional distress at baseline.

By contrast, the HCS items may mirror one of the

primary goals of cardiac rehabilitation, i.e. enhancing functional status and perceived health. This

hypothesis was tested in a sample of 120 patients

with CHD, 60 of which participated in the Antwerp

rehabilitation program. Previous research in this

sample of patients indicated that the 60 rehabilitation subjects, but not the 60 control subjects, rePsychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)

ported a significant increase in well being and positive affect and a significant decrease in disability

and negative affect as measured by the Heart Patients Psychological Questionnaire and the Global

Mood Scale (3, 5). There also was significantly less

tranquilizer use in the rehabilitation group than in

the control group.

In the present study, there was no significant

difference between the rehabilitation and control

subjects with reference to age, medical category, or

HCS scores at baseline. Repeated measures MANOVA indicated a significant rehabilitation x time

interaction effect for somatic as well as cognitive

health complaints (Table 7). In other words, changes

in HCS scores differed as a function of treatment.

Three months after the initial assessment, rehabilitation subjects, but not control subjects, reported a

significant decrease in somatic and cognitive health

complaints (p < .0001). This finding suggests that

the HCS reflected the changes in perceived health

that occur during cardiac rehabilitation. Test-retest

reliability (3-month period) of the HCS scales in the

control group was r = .73 and r = .69, respectively

(N = 60).

In general, the findings of Study 2 were consistent

with the notion that the HCS measures a construct

that is not tapped by standard scales of psychopathology. First, factor analysis yielded a distinct distress

factor that had its highest loadings on the HCS and

the Heart Patients Psychological Questionnaire but

not on any of the SCL-90 symptom dimensions.

Second, the HCS had a higher mean score than the

SCL-90, despite the fact that both scales have the

same format. It should be remembered that theoretical relevance and frequency of endorsement were

used as criteria for the selection of items comprising

the HCS. Accordingly, the HCS displayed a normal

clustering of scores. By contrast, the narrow range

of SCL-90 scores indicates that most patients with

471

J. DENOLLET

CHD affirm only a small number of items. Third,

the HCS reflected the clinical changes that occur

during cardiac rehabilitation, whereas previous research found the SCL-90 to be less sensitive to assess

change in this context (3). Hence, the HCS did meet

the criteria of content validity, appropriateness, and

responsiveness.

The nonrandom assignment of subjects to rehabilitation and control groups, however, requires a

conservative interpretation of some findings, and

more research is needed to examine the notion that

health complaints are more than mere markers of

psychopathology in this setting. With reference to

this issue, I do not suggest that research should

ignore the coronary patient's level of psychopathology. On the contrary, evidence indicates that symptoms of psychopathology are associated with an adverse prognosis in patients with CHD (e.g., reference

33). Measures such as the SCL-90 may serve as a

screen to detect patients that are more vulnerable

to serious health problems in the years after a coronary event. However, in addition to assessing

where the patient is in terms of psychopathology, it

is also important to assess other psychological constructs that are relevant in the context of CHD. That

is, the strategy of defining quality of life by the

absence of psychopathology leads to underestimates

of actual changes in quality of life (3). The findings

of Study 2 suggest that an instrument that is sensitive to common problems of patients with CHD (such

as the HCS) better mirrors the changes in perceived

health status in the weeks and months after a coronary event.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Validation is an ongoing process of obtaining multiple sources of empirical evidence to assess whether

the instrument actually measures what it purports

to (31). It is important to note that this paper does

not provide evidence for the predictive validity of

the HCS. More research is needed to examine the

utility of this new instrument for the prediction of

disease outcome or treatment effects. With reference

to this issue, it is not clear whether the HCS is

superior to other, more general instruments. The

present research only examined the superiority of

the HCS over the SCL-90 for assessing the effect of

cardiac rehabilitation on quality of life.

However, the contribution of this research is

mostly methodological in that it describes the rational development of a potentially useful instrument. Three major principles undergird the devel472

opment of the HCS: a) the HCS is based on a clear a

priori model. The accuracy of this model was tested

with the use of appropriate multivariate statistical

procedures (27); b) the items of the HCS are relevant

from the patient's point of view. The patient was

considered to be the best informant on the way in

which illness affects well being (29); and c) the HCS

is responsive to a clinical intervention. Responsiveness to change was considered to be a dimension of

validity that incorporates longitudinal information

(i.e., change) (31). These methodological issues apply

equally well to other health-related outcome measures.

On the assumption that validity should be built

into a scale from the outset, this paper describes a

new measure of health complaints that are relevant

to patients with CHD. Ideally, the HCS had to be

psychometrically sound, sensitive to change, and

easy to administer. The HCS demonstrated a sound

factor structure that accounted for a large proportion

of variance at both the first- and second-order level

of assessment and was found to have high internal

consistency (a > .80) and adequate test-retest reliability over a 3-month period (r > .69). Significant

correlations with widely used distress measures

(STAI and SCL-90) and with a measure that was

designed for cardiac patients (Heart Patients Psychological Questionnaire) provided evidence for its construct validity. Furthermore, the HCS was largely

unrelated to self-deception or social inhibition, and

sensitively reflected changes in perceived health

that occur frequently in patients with CHD. In addition to psychometric soundness and sensitivity,

the HCS is appealing in its practicality; the scale is

brief and easy to use in a medical setting.

With reference to this issue, the HCS appears to

have broad applicability. Apart from the cardiopulmonary complaints, the items of the HCS may monitor outcomes for other chronic medical conditions

as well. As a matter of fact, the majority of health

complaints of the HCS are symptoms that would be

associated with any serious health or psychiatric

problem. However, cross-validation in other patient

groups is needed. Although both instruments are

closely related, the HCS is distinctive from the Heart

Patients Psychological Questionnaire. The Heart Patients Psychological Questionnaire comprises a mixture of 24 health-related items (i.e., disability and

well-being scales), 16 personality items (i.e., neuroticism and social inhibition scales), and 12 filler

items. As a consequence, the HCS is shorter (24 vs.

52 items) and more straightforward than the Heart

Patients Psychological Questionnaire. Moreover, the

Psychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)

HEALTH COMPLAINTS IN CHD

Heart Patients Psychological Questionnaire does not

comprise somatic health complaints.

An unsolved problem, however, concerns the degree to which the present results would generalize

to female patients with CHD. Furthermore, the convergent validity of the HCS was examined by direct

comparison to only one measure of perceived health

in cardiac patients. Another important issue is the

meaning of health complaints per se in patients with

CHD. That is, the reporting of health complaints is

not only dependent on physiological factors, but also

on psychological factors (34). It is by now well established that symptom reporting is influenced by common beliefs about disease (35), the amplification of

bodily sensations (36), and the tendency to interpret

bodily sensations as signs of disease (23). Accordingly, complaints of chest pain (37), dyspnea (38),

fatigue (5), and sleep problems (39) are often a function of psychological distress. Although some individuals tend to overperceive symptoms, others may

fail to report significant bodily sensations (40).

Clearly, self-reported health complaints are error

prone and do not always parallel the objectively

assessed health status. Nonetheless, I believe health

complaints should not be ignored in the context of

CHD.

First, the assessment of health complaints may

serve as a rough screen to identify a subset of patients that are more liable to long-term health complications. Self-report health scales are likely to have

two distinct components: one that is psychological

and another that is health related (23). In other

words, the fact that symptom reporting is biased

does not mean that health complaints cannot also

play a true role in CHD (9-13). In fact, symptom

reporting (41) and poor self-rated health (42) have

been associated with a poor prognosis in patients

with documented CHD. Research also suggests that

coronary spasm may be an organic source of chest

pain in the absence of angiographically documented

CHD (43). Of course, it is unfortunate that most

health complaints, such as discomfort in the chest

or undue fatigue, are not specific of CHD. Nonspecific symptoms do not help a clinician make decisions concerning prognosis and therapy, but they do

warrant further examination of the patient in question. Dismissing measures of perceived health as

merely indicating the illegitimacy of symptom reports may result in the delay of much needed treatment in some coronary patients.

Second, a finely tuned assessment of health complaints may help to evaluate the treatment of patients with CHD. Mortality is not the only outcome

worth studying (1). In fact, a primary goal of health

Psychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)

care for coronary patients is to enhance daily functioning and well being (44). Among other things, this

implies the identification of coronary patients at risk

of "medically unnecessary" disability as early as

possible so that they may be given extra help (29).

Another important issue concerns the effect of drug

therapy on quality of life (45).

Unquestionably, the pervasive influence of psychological biases, such as the tendency to experience distress, is a factor with which to be reckoned

in the context of CHD (4). I merely want to stress

that health complaints, albeit subjective in nature,

should be accurately assessed in patients with CHD.

As pointed out by Goodwin (46): " All too often,

excellent papers describing results of sophisticated

research techniques in groups of patients pay little

attention to the clinical aspects studied or to the

patients and their symptoms.. . " Evidence suggests

that quality of life can best be evaluated by patients

themselves (47). The findings of this paper suggest

that the HCS may be of benefit in this area of

research.

This research was supported by a grant of the

National Fund for Scientific Research, Brussels, Belgium.

1 thank Hugo Pauwels at UFSIA for his help in

analyzing the data. I am also indebted to three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments on an

earlier draft of this article.

REFERENCES

1. Schroeder SA: Outcome assessment 70 years later: Are we

ready? N Engl J Med 316:160-162, 1987

2. Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al: Functional status

and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: Results

from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 262:907-913, 1989

3. Denollet J: Sensitivity of outcome assessment in cardiac rehabilitation. J Consult Clin Psychol 61:686-695, 1993

4. Denollet J: Negative affectivity and repressive coping: Pervasive influence on self-reported mood, health, and coronaryprone behavior. Psychosom Med 53:538-556, 1991

5. Denollet J: Emotional distress and fatigue in coronary heart

disease: The Global Mood Scale (GMS). Psychol Med 23:111121,1993

6. Manning WG, Wells KB: The effects of psychological distress

and psychological well-being on use of medical services. Med

Care 30:541-553, 1992

7. Smith GR, O'Rourke DF: Return to work after a first myocardial infarction. A test of multiple hypotheses. JAMA 259:

1673-1677, 1988

8. Mulcahy R: Twenty years of cardiac rehabilitation in Europe:

A reappraisal. Eur Heart J 12:92-93, 1991

9. Alonzo AA, Simon AB, Feinleib M: Prodromata of myocardial

infarction and sudden death. Circulation 52:1056-1062,1975

10. Cook DG, Shaper AG. Breathlessness, angina pectoris, and

coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol 63:921-924, 1989

11. Appels A, Mulder P: Excess fatigue as a precursor of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart ] 9:758-764, 1988

473

J. DENOLLET

12. Carney RM, Freedland KE, Jaffe AS: Insomnia and depression

prior to myocardial infarction. Psychosom Med 52:603-609,

1990

13. Wingard DL, Berkman LF: Mortality risk associated with

sleeping patterns among adults. Sleep 6:102-107,1983

14. Mattiasson I, Lindgarde F, Nilsson JA, Theorell T: Threat of

unemployment and cardio-vascular risk factors: Longitudinal

study of quality of sleep and serum cholesterol concentrations

in men threatened with redundancy. Brit Med J 301:461-466,

1990

15. Zonderman AB, Heft MW, Costa PT: Does the Illness Behavior

Questionnaire measure abnormal illness behavior? Health

Psychol 4:425-436, 1985

16. Kaplan GA, Camacho T: Perceived health and mortality: A

nine-year follow-up of the Human Population Laboratory

cohort. Am J Epidemiol 117:292-304,1983

17. Reuben DB, Rubenstein LV, Hirsch SH, Hays RD: Value of

functional status as a predictor of mortality: Results of a

prospective study. Am ] Med 93:663-669, 1992

18. King AC, Taylor CB, Haskell WL, DeBusk RF: Influence of

regular aerobic exercise on psychological health: A randomized, controlled trial of healthy middle-aged adults. Health

Psychol 8:305-324, 1989

19. Gallacher JE, Smith GD: A framework for the adaptation of

psychological questionnaires for epidemiological use: An example of the Bortner Type A scale. Psychol Med 19:709-717,

1989

20. Pilowsky I, Spence ND, Waddy JL: Illness behaviour and

coronary artery bypass surgery. ] Psychosom Res 23:39-44,

1979

21. Erdman RA, Duivenvoorden HJ, Verhage F, Kazemier M,

Hugenholtz PG: Predictability of beneficial effects in cardiac

rehabilitation: A randomized clinical trial of psychosocial

variables. J Cardiopulm Rehabil 6:206-213,1986

22. Derogatis LR, Lipman RS, Covi L: SCL-90: An outpatient

psychiatric rating scale - Preliminary report. Psychopharmacol Bull 9:13-27, 1973

23. Watson D, Pennebaker JW: Health complaints, stress, and

distress: Exploring the central role of negative affectivity.

Psychol Rev 96:234-254,1989

24. Van Der Ploeg HM, Defares PB, Spielberger CD: ZBV. Een

Nederlandstalige Bewerking van de Spielberger State-Trait

Anxiety Inventory. [ZBV. A Dutch-language adaptation of the

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory]. Lisse, The Netherlands, Swets

and Zeitlinger, 1980

25. Crowne DP, Marlowe D: A new scale of social desirability

independent of psychopathology. J Consult Psychol 24:349354,1960

26. Comrey AL. Factor-analytic methods of scale development in

personality and clinical psychology. J Consult Clin Psychol

56:754-761, 1988

27. Joreskog KG, Sorbom D. LISREL VI: Analysis of linear structural relationships by the method of maximum likelihood.

Chicago, International Educational Services, 1985

474

28. Frasure-Smith N, Prince R. The Ischemic Heart Disease Life

Stress Monitoring Program: Impact on mortality. Psychosom

Med 47:431-445, 1985

29. Mayou R, Bryant B: Quality of life in cardiovascular disease.

Br Heart J 69:460-466,1993

30. Bindman AB, Keane D, Lurie N: Measuring health changes

among severely ill patients: The floor phenomenon. Med Care

28:1142-1152, 1990

31. Hays RD, Hadorn D: Responsiveness to change: An aspect of

validity, not a seperate dimension. Qual Life Res 1:73-75,

1992

32. Arrindell WA, Ettema JH: SCL-90 Handleiding. [SCL-90 Manual]. Lisse, The Netherlands, Swets and Zeitlinger, 1986

33. Ahem DK, Gorkin L, Anderson JL, et al: Biobehavioral variables and mortality or cardiac arrest in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Pilot Study (CAPS). Am J Cardiol 66:59-62,1990

34. Pennebaker JW: The Psychology of Physical Symptoms. New

York, Springer-Verlag, 1982

35. Pennebaker JW, Epstein D: Implicit psychophysiology: Effects

of common beliefs and idiosyncratic physiological responses

on symptom reporting. J Pers 51:468-496,1983

36. Barsky AJ, Goodson JD, Lane RS, Cleary PD: The amplification

of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med 50:510-519,1988

37. Costa PT, Zonderman AB, Engel BT, Baile WF, Brimlow DL,

Brinker J: The relation of chest pain symptoms to angiographic findings of coronary artery stenosis and neuroticism.

Psychosom Med 47:285-293,1985

38. Bass C, Gardner W: Emotional influences on breathing and

breathlessness. J Psychosom Res 29:599-609,1985

39. Ford DE, Kamerow DB: Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders: An opportunity for prevention? JAMA 262:1479-1484, 1989

40. Barsky AJ, Hochstrasser B, Coles NA, Zisfein J, O'Donnell C,

Eagle KA: Silent myocardial ischemia. Is the person or the

event silent? JAMA 264:1132-1135, 1990

41. Shekelle RB, Vernon SW, Ostfeld AM: Personality and coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med 53:176-184. 1991

42. Orth-Gomer K, Unden A, Edwards M: Social isolation and

mortality in ischemic heart disease: A 10-year follow-up

study of 150 middle-aged men. Acta Med Scand 224:205-215,

1988

43. Maseri A: Coronary vasoconstriction: Visible and invisible. N

Engl J Med 325:1579-1580, 1991

44. Denollet J: The psychological effect of cardiac rehabilitation

(abstract). Psychosom Med 55:120-121, 1993

45. Dimsdale JE: Reflections on the impact of antihypertensive

medications on mood, sedation, and neuropsychologic functioning. Arch Intern Med 152:35-39, 1992

46. Goodwin JF: The clinical approach - Cui bono ? Eur Heart J

12:751-752, 1991

47. Slevin ML, Plant H, Lynch D, Drinkwater J, Gregory WM:

Who should measure quality of life, the doctor or the patient?

Br J Cancer 57:109-112, 1988.

Psychosomatic Medicine 56:463-474 (1994)