NEGLECT Stephen R. Milanowski B.F.A.Cranbrook Academy of Art

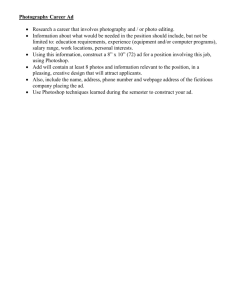

advertisement