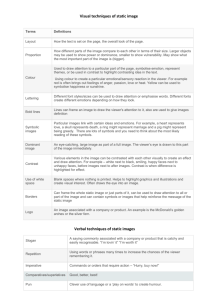

A System of Formal Analysis for Architectural

advertisement