Reasoning and Argument Analysis Clark Wolf Director of Bioethics Iowa State University

advertisement

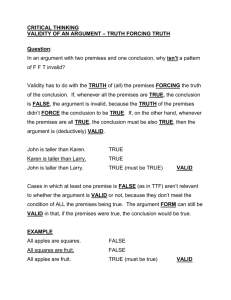

Reasoning and Argument Analysis Clark Wolf Director of Bioethics Iowa State University jwcwolf@iastate.edu OBJECTIVES: On completion of this unit, students should be able… 1.1 …to recognize when they are presented with an argument, 1.2 …to analyze arguments by identifying the conclusion and distinguishing conclusions from premises. 1.3 …to evaluate arguments by considering the plausibility of the premises and the extent to which the premises support the conclusion. 1.4 …to distinguish deductive and inductive arguments, 1.5 …to distinguish an argument’s content from its form. 1.5 …to define key concepts: argument, premise, conclusion, evidence, rationally persuasive argument, fallacy, valid argument, invalid argument, inductive argument, abductive argument. 1.6 …to evaluate arguments, by (i) distinguishing premises from conclusion, (ii) putting the argument in standard form, (iii) critically examining the premises, and (iv) evaluating the inference from premises to conclusion. 1.7 …to be self-reflectively critical of their own arguments and those of others. What is an Argument? Argument: A set of statements, some of which serve as premises, one of which serves as a conclusion, such that the premises purport to give evidence for the conclusion. Premise: A premise is a statement that purports to give evidence for the conclusion. Evidence: To say that a statement A is evidence for another statement B is to say that if A were true, this would provide some reason to believe that B is true. Conclusion: The statement in an argument that is supposedly supported by the evidence. When do we encounter arguments? Any time anyone tries to persuade you of something, or to make you change your mind. Rational persuasion uses reasons, but even irrational persuasion employs reasons (bad reasons). In evaluating arguments, we need to be able to evaluate reasons and patterns of reasoning. Indicator Words: Indicator words: Sometimes writers use language that indicates the structure of the argument they are giving. The following words and phrases indicate that what follows is probably the conclusion of an argument: Therefore… thus… for that reason… hence… it follows that… Conclusion Indicators: Because… Since… For… For the reason that… Example: “Because animals are conscious, capable of experiencing pain and pleasure, they are like people in significant respects. Since they are also intelligent—often far more intelligent than newborn babies for example, it follows that they deserve kind treatment from human beings and that it is wrong to treat them with cruelty.” Examples: Since private business is the most effective instrument of economic change, the government should utilize the resources of private business in its economic planning and decision making. Women work just as hard as men and are just as productive. Therefore they should be compensated the same. Standard Form Standard Form: Usually we find arguments expressed in ordinary prose. But as noted, when we are evaluating arguments it is a good idea to separate the premises from the conclusion, and to put the argument into “standard form.” We say that an argument is in standard form when the premises are numbered and listed separately, and when the conclusion is clearly written underneath them. Standard Form Version: (1) Animals are conscious. (2) Animals are capable of experiencing pain and pleasure. (3) Animals are intelligent. (4) Animals are like people in significant respects. Conclusion: (5) Therefore (i) animals deserve kind treatment from humans and (ii) it is wrong to treat animals with cruelty. A Reservation: Whenever we put an argument in standard form, we have given an interpretation of that argument. Ideally, an interpretation should accurately capture the meaning of the original, but it is always possible to challenge the accuracy of an interpretation. Evaluating an Argument: “By splicing genes into crop plants, scientists have changed these crops in ways that never could have come about through the natural process of selective breeding. These changes in our food crops threaten the health of everyone in the world, and impose a great danger of massive environmental damage. Genetically modified crops are unnatural and dangerous. We should avoid using them and growing them, and should do whatever it takes to eliminate them from Iowa farms.” Questions: What is the author of this passage trying to persuade you to believe? (What’s the conclusion?) What reasons are being offered? (What are the premises?) In this argument there are few indicator words used, but it is not hard to figure out what the author would like us to believe. What’s the Conclusion? Conclusion: Often the conclusion of an argument is stated either in the first sentence of a paragraph, or in the last sentence of the paragraph. In this case, the conclusion—the claim the author intends to persuade us to accept—is a complex claim. The author urges that: (1) We should avoid using and growing genetically modified crops, and (2) We should do “whatever it takes” to eliminate these crops from Iowa farms. What’s evidence or reasons are given? Premises: P1) Gene splicing changes crops in ways that could never have come about through selective breeding. P2) Changes in food crops due to gene splicing threaten everyone’s health. P3) Changes in food crops pose a threat of massive environmental damage. P4) Genetic modification of crops is unnatural. P5) Genetic modification of crops is dangerous. Step One: Are the premises true? Premise 1: Gene splicing changes crops in ways that never could have come about through selective breeding. Evaluation: Is this true? Some of the properties that have been induced through genetic engineering might have been produced through selective breeding. But it is unlikely that the genetic alterations that have been effected in the production of genetically modified crops would have been produced in any other way. Perhaps this premise should be somewhat qualified, but it contains a kernel of truth. Step One: Are the premises true? Premise 2: “Changes in food crops due to gene splicing threaten everyone’s health. Evaluation: This claim requires additional support and evidence. Many people are concerned about the health effects of genetically modified food crops, but no one has shown that these crops are dangerous. The author of the paragraph provides no evidence that genetically modified crops are dangerous. Step One: Are the premises true? Premise 3: Changes in food crops pose a threat of massive environmental damage. Evaluation: Once again, this claim requires support. There may indeed be reasons for concern about the environmental effects of genetically modified crops, but the author has not given us any evidence. Without more evidence, we may not be in a position to evaluate this premise. Step One: Are the premises true? Premise 4: Genetic modification of crops is unnatural. Evaluation: The term ‘natural’ can be slippery, and we may need to know more about what the author has in mind. In context, it seems that the author regards things that are ‘unnatural’ as bad. But in an important sense, bridges, computers, vaccines and artworks are “unnatural.” Step One: Are the premises true? Premise 5: Genetic modification of crops is dangerous. Evaluation: Once again we need evidence for such a claim before we can place our trust in it. In what sense is genetic modification dangerous, and what are the specific dangers the author has in mind? Without more evidence, we may simply find that we are not yet in a position to evaluate the argument. Step Two: If the premises were true, would they provide good evidence for the conclusions? Are there implicit premises that should be included in the evaluation of the argument? A Strategy for Evaluating Arguments: Of course, for the purposes of this course, your views about GM crops are not what matter. What does matter is the strategy used here for evaluating the argument under consideration: First, identify the argument’s premises, and restate them clearly. Second, evaluate each premise individually: is it true or false? What evidence, what information would you need to know in order to determine whether the premises are true? If you discover that the premises of the argument are simply false, you may need to go no further. But if the premises seem true, there is a third important step to take in evaluating the argument: Third, consider the relationship between the premises and the conclusion. What kind of argument is it? Is it a good argument of its kind? Fallacies: Fallacy: An argument that provides the illusion of support, but no real support, for its conclusion. Evaluating Philosophical Arguments: Fair-Mindedness and the State of Suspended Judgment: When evaluating arguments, we should strive to be impartial and fair-minded. We should try to follow where the best reasons lead instead of pre-judging the conclusion. Argument for Analysis: There is no universal standard for right and wrong. Different people simply have different views and different values. None of us is in a position to say that our values or our moral judgments are privileged, or that they are uniquely better than the judgments of others. What do we learn from the Bloggs Cases? Ethical Theory: We reveal our ethical views when we explain or justify our choices and behavior to others. Ethical views can be thoughtless and unreflective, or thoughtful and reflective. To the extent that we’re thoughtless and unreflective, our value system will lack integrity and depth. If our values are shallow and incoherent, we will make bad decisions, …and we will be shallow and incoherent. (?) Stop here… ON TO PLATO! Reasoning in Ethics: Rachels notes that “philosophy is not like physics. In physics, there is a large body of established truth, which no competent physicist would dispute and which beginners must patiently master. (Physics instructors rarely invite undergraduates to make up their own minds about the laws of thermodynamics.)” (ix-x) Reasoning in Ethics 1.1 The Problem of Definition: A theory of morality is a theory about how we should live and why. It turns out to be impossible to give a simple definition of ‘morality.’ This should make us cautious, but shouldn’t dissuade us from investigating the subject further. In this book we will examine alternative theories of morality, consider the reasons that support or oppose each of them, and come to evaluative judgments. Reasoning in Ethics: What is the “Minimal Conception of Morality” that Rachels offers? Is it as ‘minimal’ as he thinks? Do we need a common minimum before we can reason about moral questions? Bloggs Cases Moral Theory Metaethics: What is morality? Where does moral value come from? Normative ethics: What principles identify right and wrong conduct? Applied/practical ethics: What are the salient ethical considerations in evaluating specific practices, actions, or technologies? Bloggs Case #1 Bloggs Case #1 “Utilitarianism”: The ethical thing to do is that which maximizes aggregate benefit for everyone. “The common good” Bloggs Case #2 Rights: Would slicing and dicing Bloggs violate his rights? (What are rights?) A person has a right just in case our obligations toward her are based on the effect that our treatment will have on her, not on others. Animals have rights just in case our obligation to treat them humanely are based on the effect that this treatment would have on the animals themselves, not the effect it would have on other people. Bloggs Case #2 Response: Slicing and dicing Bloggs would violate his rights. A moral right is a justified claim that an individual (or group) may make to certain objects or certain treatment by others. Bloggs’s right to X may take the form of: A claim that Bloggs may make to a particular object (e.g., his kidneys) A constraint on how Bloggs should be treated (e.g., he shouldn’t be killed for his organs) An obligation on others not to interfere with Bloggs’s doing X (e.g., his continuing to live) Ethical Theory Kant: Categorical Imperative: “Act only such that you could will the maxim on which you act as a universal law.” “Act so that you treat humanity, whether in your own person or that of another, always as an end in itself, and never as a means only.” Would ‘slicing and dicing’ Bloggs for his organs involve treating him as a mere means? Ethical Theory: Killing v. Letting Die: It has sometimes been argued that we have a moral duty not to kill, but no moral duty (or a lighter moral duty) not to let people die. Does this distinction explain why we shouldn’t kill Bloggs for his organs? Bloggs Case #3 Bloggs Case #3 The ethics of acts vs. omissions The greater good vs. “clean hands” Ethical Theory: We reveal our ethical views when we explain or justify our choices and behavior to others. Ethical views can be thoughtless and unreflective, or thoughtful and reflective. To the extent that we’re thoughtless and unreflective, our value system will lack integrity and depth. If our values are shallow and incoherent, we will make bad decisions, …and we will be shallow and incoherent. (?) Fini. Rachels’ Examples: Baby Theresa Jodie and Mary Tracy Lattimer Case Case of Fauziua Kassindja What should we glean from these cases? 1) 2) 3) Some Basic Moral Considerations: Benefit to others, Do no harm, Sanctity of life, truth telling, etc. Is there a basic common moral minimum? Moral judgments have reasons: they are supported by our beliefs, and by lines of reasoning. Therefore we can critically evaluate our moral judgments using the tools of argument analysis. Moral Reasoning: Whether we agree about the verdicts in these cases or not, we can agree that our moral judgments are based on reasons, that we can articulate these reasons and evaluate them, that we can examine how competing reasons interact with one another. Morality is therefore about reasoning, not just about reasonless or intuitive judging. Requirement of Impartiality: This, according to Rachels, is the idea that every person’s interests are equally important from the moral point of view. Impartiality of this sort is a commitment. Next: Deductive Arguments and Moral Relativism Deductive Argument: An argument that has the property that if the premises are true, then the conclusion cannot be false. Example: All vertibrates have hip bones. Snakes are vertibrates. Therefore, snakes have hipbones. Cultural Relativism “There is no universal standard for right and wrong. Different people simply have different views and different values. None of us is in a position to say that our values or our moral judgments are privileged, or that they are uniquely better than the judgments of others.” We will not cease from exploration And the end of our exploring Will be to arrive where we started And know the place for the first time. --T.S. Eliot, Four Quartets An Argument for Analysis: All loyal Americans should proudly vote for George Bush in the upcoming election. In times of crisis, we should avoid loosing face before the world community by voting a proven leader out of office. George Bush has shown that he can make decisive and forceful decisions, and his efforts in Afghanistan and Iraq have earned him the respect of the American people, and of our allies overseas. It is unthinkable that we might vote such a leader out of office. Argument for Analysis: Only by replacing Bush can we hope for a peaceful exit for our troops in Iraq and Afghanistan. Because the Iraqui and Afghan people regard US troops as conquering invaders, they hate our soldiers and take every opportunity to harm and abuse them. Because of this, US troops are uniquely ill-suited to bring order and stability to these war torn nations. Only an international force could gain the trust of the people of Iraq and Afghanistan, and only a force that gains their trust can maintain stability and peace. But George Bush has squandered the good will of the international community, and it is unlikely that any international force will help us while he is in office.