Document 10689621

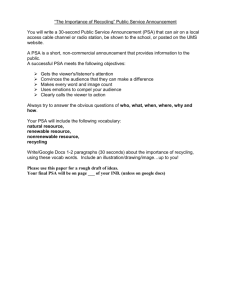

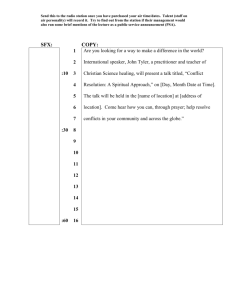

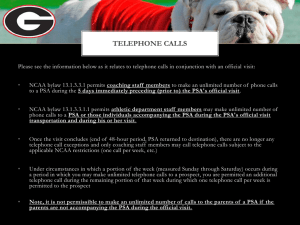

advertisement